I. TO DOUGLAS HEAD WITH EXTENSION TO PORT SODERICK.

FOR the opening morning of your holiday, particularly in the case of a first visit to the Island, not too long a walk is recommended which, besides being enjoyable in itself, will give you a good bird's eye view of the district around and behind Douglas, and some indication of what may be anticipated when the time comes to explore further afield.

Starting south along the promenade take the toll-bridge (three-halfpence each way) which crosses the harbour, and climb the flight of steps immediately opposite. Then turn left along the road for a rather dull five minutes until the old golf-club house is reached on the left. Directly opposite to this is a gate and, beyond, a footpath which leads up the slope towards a ruined cottage.

At this point it may be a temptation to pause and scan the view but my advice is to wait until the top is attained a few hundred yards further on. Then, indeed, you may look back and admire. The main feature of the scape is the mighty sweep of Douglas Bay with its background of Mona's highest mountains. There is Snaefell, nine miles away, more or less straight over the Tower of Refuge, and also a strip of North Barrule, the second highest in the island. To the east it may be just possible to identify Scafell in the Lake District, if the weather be sufficiently clear. On the whole it is to be hoped than on this occasion it will not be possible. Immediately below are the lively piers as also the aforesaid Tower of Refuge, built in 1832 by the Sir William Hillary who founded the Royal National Lifeboat Institution and who designed the tower as a shelter for any who might be wrecked on the rock on which it stands.

Altogether a delectable survey, but more is to come if' you decide to go on to Port Soderick. In this event, proceed more or less in the same direction but now downhill, bearing to the left, and in a few minutes Marine Drive is reached, the finest thing in the British Isles of its kind, according to some. How it compares with the drive round the Great Orme's Head at Llandudno or with the Antrim Coast Road in Northern Ireland is a matter of individual taste. Suffice it here to say that all of them are good.

Blasted out of the perpendicular face of the cliff, the Marine Drive runs for about three miles to Port Soderick. In pre-war days there was an electric railway along the drive but this is now derelict. Several chasms en route are traversed by bridges and there are named features which it may be amusing to try and identify : for example the Nun's Chair, in which it is reputed that recalcitrant nuns used to be forced to sit as a penance, and, more especially, the Horse Leap down which, according to tradition, a pack of hounds fell in pursuit of a hare, while the huntsman was saved by the horse leaping the chasm.

Port Soderick could be an even nicer place if man had not striven so strenuously to improve on nature.

For the return to Douglas there are three possibilities. Almost the best is to go back the same way, for after all, taken in reverse, the Marine Drive offers quite a different set of views. Substantially shorter is the direct road back, followed by taking the first and only fork to the left on the way back from Port Soderick. The last alternative is to pick up a train from Port Soderick station.

In any case the whole trip can be done in a morning although an early start will be necessary if it is desired to walk not only out but home again.

II. THE DOUGLAS END OF THE GREAT CENTRAL VALLEY.

ONE of the advantages of excursions along the Valley is that they can be begun and ended at any of the stopping places either of the 'buses or the Isle of Man Steam Railway. For example, a walk, well suited to wet weather because it is almost entirely along hard roads, can be started from Crosby, which is only twenty minutes in the 'bus from Douglas. Crosby is in the parish of Marown, the only one in the island which does not touch the sea at any point. Turn left from the main road, over the railway and up the hill. In half a mile Marown Old Church is reached, with an ancient doorway, a font of Manx granite and some not very interesting Celtic crosses. The hill to the south is Slieu Chiarn (636 feet) and, in a field on its north-west slopes called Magher-y-Chiarn, which means "The Field of the Lord" is the notable St. Patrick's Chair. This consists of upright stones on a platform, forming a seat, and from it St. Patrick is reputed to have blessed the people of the Isle of Man before leaving them.

Back on the road, continue uphill and keep left all the time round the other side of Slieu Chiarn. Once this is passed a wide view opens out over the valley to the north which is said to have inspired the one-time famous artist John Martin to paint his picture, The Plains of Heaven. A print of this can be seen in the Manx Museum. Ten minutes beyond the hamlet of Braaid are the stone circles of Glen Darragh, which means 'Oak Glen'. The trees are very largely gone but what was probably a burial place remains. After this the first left-hand turning can be taken down to the 'bus-stop at Union Mills, making a round tramp of an easy two hours and a half or, preferably, the second turning can be taken down to Kirk Braddan, which takes fifteen minutes longer.

In the churchyard are two tombstones—if you can find them in the absence of a knowledgable local. One on the right of the doorway commemorates the Rev. P. Thompson, who had his stone carved and his grave dug in 1673 but did not die until 1689. The inscription is to the 'Minister of God's Word, 40 years, AT PRESENT Vicar of Kirk Braddan.' The other memorial is to Samuel Ally, a slave who served a Manxman who guarded Napoleon in St. Helena and who claimed the black slave as his friend as well as his servant.

The church stands in the valley of the river Dhoo, just over two miles north-west of Douglas. Here again, it is easy to get a lift back, but if the walk is preferred the road up the hill can be followed for half a mile, when a gate on the left gives entrance to a green track, which can be muddy. Follow this round to the left through a farmyard (here again, plenty of mud) and on again to another road.

Turn right for a few hundred yards up the hill and then left into another farmyard. In the left-hand bottom corner a gate and the track beyond lead down across the municipal golf-links to one of the clumps of ugly houses, the grey ones. A little way past the modern catholic church a sign points to the right. 'Through the Nunnery.' Follow this direction, cross the stream and there is the pleasant Lovers' Walk along the banks of the river.

To quote the words of a Manx poet, ' The walk through the umbrageous woods along the river-side, with the broad, shallow stream flowing smoothly between its tree and covered banks, is very pleasant, as it is on a hot summer's day to lie on a grassy bank, under the shade of a wide-spreading tree, and gaze dreamily at the sweet pastoral landscape around.' The Reverend T. E. Brown could certainly hymn the praises of his native isle.

We emerge from the Lovers' Walk and in a further half-mile find ourselves at the tip of Douglas Harbour.

III. A WINDING WALK FROM WINDY CORNER

A PROBLEM to solve first is how to get to Windy Corner, which is roughly six miles from the Villa Marina (approximately the centre of Douglas promenade) on the mountain road to Ramsey via Snaefell. 'There are no public conveyances on this route and unless therefore one can get a lift in a car, it will be necessary to take one of the 'buses which run two or three times a week to Baldwin.

Immediately above the village of Baldwin fork right to cross the river Glass in the West Baldwin Valley. Take the second right-hand turning through Algayre and, crossing a spur which runs down from the Garraghan mountain (1,640 feet) in front, we reach in a few minutes the East Baldwin Valley. Turning left, follow the road [continuation of B21]up parallel to the Baldwin river and, ignoring the first, a right-angle turning, follow a narrow fork to the right five minutes later and just past a chapel [now disused]on the left.

Where there is any choice of routes keep right, as this one ascends steeply to fade out into a mere track which brings you up to Windy Corner, two miles from the fork and four miles from Baldwin village.

From Windy Corner take the right-hand of two tracks on the right of the road. This leads steadily downhill practically due east and there are good views all round. The peak quite close on the right of the track is Carn Gerjoil (1,460 feet). In about a mile stone walls begin to line the track, which emerges through a gate to become a road a little further on. Here you are recommended to deviate to the right, passing through a farmyard about 150 yards up the slope. From here as much or as little time as taste decrees may be spent in exploring the upper reaches of Glen Roy. Here the scenery is definitely that of Scotland. Returning through the farmyard, follow your original course down in a few moments to the point at which it crosses the stream. This is a lovely spot. Here vehicles traverse a water splash, while there is a foot-bridge for pedestrians both to a road which will take you down direct into Laxey in half an hour. A preferable alternative, suggested for the adventurous only, is to follow the footpath running down, the left bank of the stream in the depths of the glen, refusing to be put off by an initial stone wall or a few strands of barbed wire.

Further progress depends on whether your luck is in. The river swoops down in head long fashion and below a fall there are stepping stones which can be crossed if there is not too much water. Otherwise, and at the worst, one must, at a point where further advance is barred by another glen which comes in from the left, scramble out of the glen, cross a couple of fields as far as a wire fence, and then follow this up to the left to a ruined cottage on the skyline, just beyond which the original road is picked up again and followed round to the right in a wide sweep. You pass several ruined cottages and, eventually, past Ballacowin, run straight down the hard road into Laxey.

The amount of time to be devoted here to the Great Wheel depends partly on taste and also on the time at which a suitable electric train or 'bus back to Douglas must be caught. In the abstract a visit to the Wheel, officially known as the Isabella, may not seem very exciting, but actually the Great Wheel vies with the Manx cat as being one of the best-known features of the Island.

When it was built in 1854 by a local engineer it was the largest wheel in the world, having a circumference of 226 feet. Its purpose was to operate the pumps which free the neighbouring lead-mines from water. It is reached by ascending the valley past a row of refreshment houses, known as Ham and Egg Terrace. Once arrived, it would be a pity not to climb the tower by a spiral staircase, from the top of which a comprehensive view of the surrouning country is enjoyed. If time admits, an hour spent in clambering about the abandoned mine-workings is also worth-while.

Altogether, it will be realised that this is an elastic walk. The total mileage, expressed in cold figures, is not impressive, especially if a short cut is made to Windy Corner, but an entire day can easily be devoted to the outing if the various attractions are to be 'done' unhurriedly. There is plenty to eat and drink in Laxey.

IV. KING ORRY'S GRAVE AND GLEN DHOON

ELECTRIC train or 'bus either from Douglas or Ramsey will take you to Minorca, just north of Laxey.

This is the area of King Orry the Norse man, who landed on the island one starry night with his Vikings. When the natives asked whence he came he pointed to the Milky Way and said 'That is the way to my country.' To this day the Manx still call the Milky Way Raad moar Ree Gorry or 'The Great Road of King Orry '.

You will find villas named after the king, and shops as well, but his well-known grave is not really much to write home about, just a few stones behind a cottage 100 yards along the road which continues, across the main road, straight up from the station.

Keep forward, half-left, where the road bears right, and in a few yards skirt the right side of a group of farm buildings. This brings you on to one of those grassy farm tracks, stony in some places, muddy in wet weather, in others. As it climbs steadily up the rise, with much gorse on either hand, you may turn to admire the view south over the valley of Laxey, while the range of high hills inland inevitably includes Snaefell which, I am in formed, is pronounced Snaefle by the Manx except when they are asked how to pronounce it, when they come over self-conscious and call it Snaefell, like the rest of the world.

In about a mile there is a narrow turning to the right just before a wider turning to the left. Follow the former, go along the side of a stone wall and straight on across the heather in front, when the wall leaves you to go to the right. There is no definite track but if you go more or less straight ahead over the skyline a stone wall, fairly difficult to traverse, must either be crossed or rounded by skirting it to the left until a gate is reached. Little but mountain and moorland can be seen while you are crossing the heather and you might well be in the midst of a wilderness. Actually the main Douglas-Ramsey road is not far away on the right.

Immediately we descend to a series of buildings, some of them derelict, which crown the beginning of Glen Dhoon. Follow the track down over the grass to a stone stile next to the trees and the main road referred to above is reached. The station is 100 yards to the right but do not be deceived into looking for refreshment at the 'Inn' marked on the map at this point for this ceased to exist years ago. There is however ample food and drink at the Glen Mona Hotel, a mile and a half to the north, which brings me to the point that this walk and the one preceding this can be fused, if desired, by taking a minor road to the south, just below the main road at Glen Mona. This joins the highway in a mile but almost at once leaves it again, forking left and coming out within a few steps at Dhoon station.

Dhoon Glen is, in some respects, the most remarkable glen in the Island. If the turn stile entrance is closed it is not too easy of access but, to the persistent, there are always ways and means of getting in.

As a spectacle it starts slowly and, for the first few minutes, it is just another glen. Then, as the path pitches headlong downwards, we realise that we are going to clamber down from a height of 600 or 700 feet to sea-level in a very short distance—less than half a mile, in fact. Just where an incautious step might precipitate us into the famous waterfall, iron railings guide us down the steps.

Some say this is the finest fall on the Island. Judged by any standard it is a fine fall, especially after rain, a proviso which it is necessary to make in the case of many other waterfalls, notably Lodore. It has a total height of 130 to 150 feet, according to which official figures you rely on, and the water pitches down in two equal stages.

The rest is a steep scramble down to the sea and up again. There are plenty of ferns and wild flowers and grand rock scenery at the bottom. It is not easy to fix a time for the proper enjoyment of this glen which will suit all parties, but it can definitely be stated that from the iron railings mentioned above back to the station and main road is an easy fifteen minutes. The entire walk from Minorca should not occupy more than two hours.

V. ST. JOHN'S AND GLEN HELEN

NO visit to the Island would be complete without the inclusion in it of an excursion to St. John's, where the Tynwald Hill is situated, and with this may conveniently be combined a trip to one of the most 'popular' of the glens in the Island, Glen Helen.

St. John's lies in the Great Central Valley which links Douglas with Peel, being eight miles from the capital and two and a half from Peel; and it can easily be reached, by bus or train from either resort.

If travelling from Douglas, there are one or two things to look out for after passing Colby. First comes the roofless, ruined St. Trinian's church, just off the high road under Greeba mountain. According to legend, every time they tried to put a roof on the church a local ogre took it off again until the attempt was given up, so that it remains without a roof to this day.

Greeba mountain (1,383 feet) is tree-clad and shapely, but it is Greeba castle which has the better claim to fame as the one-time picturesque and stately residence of undoubtedly the Island's best-seller, Hall Caine, whose own fame, however, would appear to be greater in the world at large than in his homeland. Any Manxman would rather point to the poet, T. E. Brown (1830-1897) as the foremost literary figure produced by the Island. As evidence of this the Manx Museum contains a beautiful memorial to T. E. Brown while any reference in it to Hall Caine would be hard to find.

On the opposite side of the valley and over hanging St. John's is Slieu Whualliam (1,094 feet) down which, according to tradition, witches used to be rolled in spiked barrels. Glen Maye may be reached direct from St. John's by taking the road south from the cross-roads, turning right in half a mile, and bearing to the right along a track which skirts the southern slopes of Slieu Whualliam and then descends due west into Glen Maye, three miles and a half from the starting point.

Returning to St. John's, the thing to see here is the world-famous Tynwald Hill. In fact, if you are fortunate enough to be in the vicinity on July the fifth, the day of the Manx national holiday, you will desire, as a good democrat, to participate in the ceremonies which follow a procedure almost unaltered since 1417.

The hill itself is a low grassy mount said to be composed of earth brought from all the seventeen parishes of the island. It was the Scandinavians who used in the days of the Vikings to pass their laws and settle their disputes in the open air on a hill. Similarly the various acts passed by the legislature of the Isle of Man during the preceding twelve months attain the force of law as a result of their titles being promulgated, first in English then in the Manx language, by the first of the two Deemsters on Tynwald Day, all this in the presence of the Lieutenant-Governor representing the King, who is ' Lord of Man', and all the other dignatories of the island.

Iceland has a somewhat similar custom, also dating from ancient times, but as her proceedings were interrupted for some years, those of Tynwald Day can easily claim the record as having been gone through continuously and for a longer period than anything else of the kind in the world. And yet, through all the centuries, the Lord of Man has himself presided over Tynwald on only one occasion and that quite recently, in 1945, when King George VI and his Consort graced the island's gathering with their presence.

Half an hour should suffice for an examination of Tynwald Hill, of the impressive Manx war memorial and of the adjacent St. John's church, after which the walk proper may be begun.

Go up the lane running north from the Hill to a bridge and turn half-right up and away from the north side of the stream. Crossing the main road, part of the T.T. Course, follow up a lane immediately opposite for a mile. Then, after the summit of the hill on the right has been passed, turn steeply downhill to the Valley of the Neb and on to the left for an other mile when the entrance to Glen Helen will be reached. Just before this the stream is bridged (but not crossed) by an imitation of the bridge over the Menai Straits.

Glen Helen, at least the lower portions, is not one of your simple unspoilt glens—indeed it has been exploited to the full. A million trees were planted in it 100 years ago—and a good many other things since. There is a Swiss chalet, there are kiosks and ornamental fountains, swings and weighing machines— everything, in fact to minister to the amusement of hoi polloi who flock here in their hundreds from Douglas, especially on Saturday evenings, when up to fifty coaches may be lined up outside the hotel.

Five minutes up the glen, either by the path high up on the left or by another more closely hugging the stream on the other side, and we are away from all this.

The Rhenass waterfall twenty minutes away is quite the high-spot of the Glen. ' The high wooded cliff on the right the precipitous hill side on the left, half covered with dark fir woods, the half-bare water-worn rock, the many brimming pools of clear beautiful water, flowing in a calm current beneath our feet, the white flashing water descending solidly from a height of twenty-five feet into the inner pool, and the strange roar, form altogether a picture of romantic beauty' — this is how the scene was described by the poet.

By working up the right bank of the Blaber river for a mile, a mountain track is caught up with which winds to the west round Beary Mountain (1,020 feet) then veering south via Ballanahoghty and on to the main road west of Greeba castle. Unfortunately it is half an hour's walk to a railway station whichever way you go, so it is best to rely on a 'bus for the return journey.

It is not easy to suggest a time for the entire round on account of the various attractions en route but the total distance is not less than nine miles. Ample refreshment can be obtained at the Glen Helen Hotel.

VI. FROM PEEL TO THE WILDERNESS OF NIARBYL

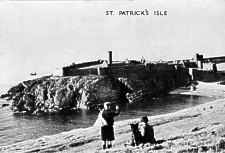

PEEL is a very old town and has plenty of history but none could call it lively, although the herring fishery can wake it up all right. Communications with Douglas are good. You can read all about Peel castle in the guide books but what they fail to mention is an unusual sundial at its entrance. This consists of a white stone at ground level with a perpendicular black line down its centre. When the shadow from the nearby archway coincides with the line they used to change the castle guard.

Now to get on with our walk. Cross the river by the bridge above the station, turn right and follow, first, the rough road and then the footpath which winds along the edge of the cliff. Corrin's Folly, reached in half an hour, was built by a dissenter who refused to be buried in consecrated ground. Stick to the path all the way to the charming Glen Maye, three miles and a half from Peel. Walk up the glen to the road and follow this as it doubles back and goes on to Dalby. We are now approaching the wildest part of the island and it would be well for the walker to look to his communications.

It will, in fact, be necessary to turn back unless you are prepared to face another six miles as the crow flies, if you continue south without hope of lift or refreshment until Colby, on the 'bus and train routes, is reached. In any event, Niarbyl Point, a long half-mile from Dalby, should be visited. Few districts in the British Isles can show a coast-line equal to that visible from this spot. If, as I hope, you decide to go on, leave the road at a fork a few minutes beyond Dalby and still keep right at Barrane, following a narrow rough track in wild and lonely country. This meanders on for a couple of miles until it returns to a good road at a ese due east of Cronk-ny-Iree-Laa (1,449 feet).

Here there is a view of South Barrule (1,585 feet) due east and to its right a wide expanse right across the south of the Island to the coast and the sea beyond. The Tower of King William College close by the airport can easily be distinguished. Incidentaily, if an east wind is blowing this can be a pretty draughty spot.

If the entire day is being devoted to this expedition it will be fun to clamber up the slopes of Cronk-ny-Iree-Laa and try to identify the ruins of a chapel somewhere in the tumble and tangle of the rocks far below, on the way to the sea. How the hermit who is reputed to have made this his abode managed to exist is a mystery.

If an hour cannot be devoted to this side show a pause can suitably be made at an obvious gap a mile and a half beyond the point at which we rejoined the road. Here the edge of the cliff can be reached by a footpath in five minutes and another sight of the coast-line enjoyed. While not so comprehensive as that from Niarbyl Point it is good enough, the striking feature being the way in which the neighbouring cliffs, nigh on 1,000 feet high, pitch nearly straight down into the sea. A mile beyond, fork left to reach Colby in another half-hour.

VII. THROUGH THREE GLENS — BALLURE, FERN AND AULDYN

RAMSEY is the nearest starting point for this walk but it can quite easily be done from Douglas by catching either 'bus or electric train to the Ballure stop, just short of Ramsey and roughly an hour's run from the capital.

A few yards from the level crossing at Ballure there are two gates on the west side of the road and either can be taken, according to whether it is desired to go through Ballure Glen or, preferably to my mind, to look down upon it from above. Assuming that the latter alternative is chosen, pass through the gate nearest the railway. This track immediately climbs up past the attractive Ballure Cottage and grounds, below on the left. Almost at once a green path forks back to the left. You can, if you like, ignore this and go straight ahead, cross the mountain road when reached, and climb up to the Albert Tower—the inevitable memorial of a royal visit in 1847— returning to the road after enjoying a view which evidently impressed the Prince Consort in no small degree.

We may prefer, however, to double back along the green path and bear round to the right past a clump of firs reminiscent of the better-known Constable's firs on Hampstead Heath. We now skirt the top edge of Ballure Glen, reaching in a few minutes a small copse of pine trees on the left. The next short path to the left leads downhill and as it is only ninety of my paces each way, you may feel it is worth while to descend this and take a near look at the Ramsey reservoir, in which positively no fishing—I repeat, no fishing—is allowed.

Resuming along the original path, a farm is passed on the right from which there is a fine view, looking due south. The track now becomes scandalously overgrown but with persistence can be followed, sometimes by taking to the green bank on the left. We are now getting well up and in a few more minutes reach the mountain road (along which the T.T. riders tear at the season of the year) which runs from Douglas to Ramsey via Snaefell. Just above the point at which we emerge on the road, the twist known as the Gooseneck is reached and rounded. Just above, a track diverges to the left which goes across the tip of Ballure Glen to reach the Old Douglas Road, now practically disused, although we shall walk along it later.

North Barrule (1,842 feet) towers in front but do not be deceived by the apparent ease of the ascent from this point. It is in fact stony and marshy and the easier way up will be indicated in a moment for the benefit of those who want to attain the second highest summit in the Island. So continue up the road until a milestone indicating that Ramsey is two miles and a quarter behind us is reached.

If the climb of North Barrule is on the agenda, go on up the road for about another mile until the only wall running right down the mountain to the roadside is reached. Pass through the gate just beyond and follow up the right side of the wall to a neck from which the summit, on the left, is easily attained.

Here may be seen all the north of the island, a bit of Scotland and of Cumberland, while Sulby Glen and Glen Auldyn on the west are revealed to their depths.

Returning to our milestone, pass through the gate a few yards away and you are at the top of Fern Glen. You are in at the birth of a glen and if it is your first introduction to the glens of Man, as it was mine, you are fortunate.

Make your way forward along any one of the tracks but take care to go down the glen and not along the top right-hand edge. Discover and descend a steep zigzag path into the heart of the glen. Opposite is a lovely little waterfall which rejoices in the pretentious name of Niagara. At the bottom of this is the place for sandwiches.

Now we go down the glen, precipitously at times, with the rivulet tumbling and tearing down alongside. This has to be crossed and re-crossed several times and there is not always a bridge. We pass masses of ferns, from which the glen takes its name, in and out of scattered trees, and finally into a silent pine wood with a thick carpet of pine needles. Five minutes later we reach the official exit from Fern Glen and soon after, passing some cottages, are in Glen Auldyn proper.

The best is now behind us. Walk down the road to the point at which the river comes back to it. There is a little artificial weir here, and 100 yards beyond a path to the right through some trees.

By sticking to our course along this, following path and minor road past Claghbane, the Ballure end of Ramsey is eventually regained, after a round trip of two easy hours, always excepting the climb of North Barrule which would, of course, add at least a couple more on to the expedition.

VIII. ROUND MAUGHOLD HEAD

THE Maughold district is best visited from Ramsey as a starting point, but if the trip has to be made from Douglas the electric railway must be taken to Dreemskerry Crossing which is only a mile from the Head, whereas the nearest point to which the buses travel is more than twice as far away.

It may be said, as introduction, that this is one of the outstanding walks on the Island.

There is a 'bus service from Ramsey to the green in front of Maughold church but it does not run very frequently, and if times do not fit it may be necessary to begin by walking along the hard high road for practically three miles from the Ballure end of Ramsey. If, however, low tide coincides with starting time the beach may conveniently be followed as far as Port Lewaigue, where it must be left. Just beyond, on a tiny headland, is an assemblage of modern houses known as the English Colony, a name which throws light on the crigin of their owners. A little further on is Port-e-Vullen, another small cove only a short step from the road and worth the slight diversion. Hence onwards it pays to stick to the road. The hills overlooking the sea on the left look tempting and, in theory, there is a track along their outer edge, but practical experience shows that if ever this existed it is now so broken and overgrown as to be well nigh impassable. So we must be resigned to a straightforward tramp of half an hour until Maughold church is reached. Kirk Maughold and its churchyard are very interesting indeed. Many eminent Manx men and women have been buried in this churchyard, the best known to the outside world being Hall Caine whose memorial is indeed beautiful. Many othér admirable and impressive monuments and tombstones will evoke attention in the course of a leisurely survey.

Passing on beyond the precincts, climb round the left side of the hill on the left until its highest point (373 feet), now a coastguard station, is attained. Looking back and around, you will gaze upon what is claimed by many to be the grandest view on the Island.

To begin with, twenty miles of coast-line are spread before you, ranging from the Point of Ayre at the northern tip of the Island to Clay Head in the south-west, between Douglas and Laxey. Practically due west is the massive bulk of the ridge, beginning with North Barrule and continuing left towards Snaefell. Underneath the hills is farmland—little fields dotted with cottages and the occasional lines of trees which soften the upper sides of a tiny glen. And, deep, deep below, is the now minute kirk with the stones of the churchyard clustering around for all the world like a shepherd and his flock.

Down again to the level by the same round about path, for the direct line is too steep for descent, and into the grounds of the lighthouse, which is one of the finest in the British Isles' and is regularly open to the public. Then leave the enclosure by a few wooden steps over the wall in the bottom right-hand corner. The line of the cliffs should now be followed in a curve to the left, either by walking in the field or on the wide top of the wall which borders it. The cliffs and the rocks from here onwards are reminiscent of Cornwall at its best, and the scene, as it changes round each corner, is quite enchanting.

A small cove crowned by a derelict chimney is entered and left by narrow paths, there are more rocks and exciting pools to explore, and then we round the corner into Port Mooar to which Hall Caine paid tribute in his book The Manxman.

This may be selected as the place for sandwiches unless the temptation to pause awhile has been too difficult to overcome at an earlier stage.

In either event we now leave the sea and strike up the lane which leads from the port, turning left at the top and right at the first opportunity. In half a mile the electric railway is crossed at Dreemskerry. Immediately after another road comes in from the right, turn left and corkscrew up past some buildings Fork left at the first opening and keep uphill. The rough lane may gradually become a watercourse but this can be avoided by taking to the fields. A small copse in front which should be skirted to the right masks the main road, and here turn left to reach The Hibernian, a group of white cottages in 200 yards.

From The Hibernian, which presumably was an inn at one time, the return to Ramsey can readily be made by the main road, down hill all the way, but a wide sweep is made round Slieu Lewaigue so that the more direct, if not the quickest route is by the Old Douglas Road via the lane which runs uphill to wards North Barrule from The Hibernian,

This is a grand finish to the circuit.

The path is lined with gorse, flaming yel low in the spring; indeed in many places there is too much of it. You will never get a better appreciation of the mighty North Barrule towering overhead than here, but do not be deceived by what appears to be the gentle gradient into thinking that its ascent from this side is as easy as it looks.

Through a gate, and Ramsey Bay begins to unfold itself with the lengthy pier in the fore ground.

Unless the local authorities have cleared the lower part of this track since these lines were written, progress now becomes virtually impossible and it is best to wind down a grass path to the Ramsey reservoir, which looks much more artificial from this viewpoint. A few minutes down Ballure Glen and we are back in Ramsey.

From three hours to three hours and a half should be allowed for the round trip, the shorter time applying if a 'bus is caught to Maughold.

IX. A SHORT WALK ABOVE RAMSEY

STARTING from the Queen's Hotel, go straight up from the South Promenade in Ramsey, turn left at the top and then right almost at once, to leave behind some ugly houses on the hillside. Soon after, the famous 'hairpin bend' on the mountain road is reached. Fifty yards up, pass through a gate (which is not there!) on the right, bear back to the right and at the corner, where there is a choice of two tracks to the left, take the right-hand one. Directions are given in some detail because it is important to start correctly. We mount beside a streamlet which runs down Elfin Glen, which is wild but open, having no trees. Follow the path as it crosses the brook and turns to ascend the other side of the gorge. Finally we wind up to a wooden fence at the entrance to a pine-wood. Go ahead through the pines, out into the open and in again, with occasional peeps at the hinterland of Ramsey, especially its golf-links, spread out immediately below. Eventually a gate leading out of the trees is passed, bringing us in a few yards to a grass track, at right-angles. Turn left along this and aim for a spot on the sky line to the right midway between the Albert Tower which has now come into view and the summit of North Barrule to the east.

Here is a choice of several paths any of which will lead in a forward direction along the right-hand edge of the top of Elfin Glen which we left a short while ago. In five minutes the mountain road is reached rounding the tip of the glen. In little more than five yards down the road we leave it again by a low stone stile which takes us, by a grass lane down the other side of the glen, in a direction pointing straight at the lake in the Mooragh Park far away at the far end of Ramsey. This lane runs down, sometimes through a bit of mud, to the junction of paths where we began to explore the glen.

This time we regain Ramsey by taking the lower portion of the mountain road, a pleasant quiet stroll to take after dinner on a fine evening or in between a late breakfast and an early lunch.

X. UP SKYHILL

THIS walk can be done from Douglas by taking the steam train as far as Lezayre but as this is only one station short of Rasey it is certainly more convenient to do it from the latter place, which is only a mile away. Starting from Ramsey along the Peel road, Milntown Hotel is passed on the left just before the cul-de-sac up Glen Auldyn. Milntown was for many generations the seat of the Christian family who have figured so prominently in the story of the Island.

The length of a field past Glen Auldyn, turn left for a few yards and then left again up a lane which works its way up Skyhill. This was the scene of quite a battle in 1077 (the Manx equivalent of our 1066). Here 300 Norsemen ambushed Fingal the King of the Manx and, as a result, the Vikings dominated the Island for 200 years.

Follow the track up as it hairpins back to the right, climbing all the time. Passing through a gate the road becomes sunken and the view, gradually opening out over the Northern Plain, is obscured by the trees on the right. It is politic therefore to scramble up the grass bank on the left as soon as may be, when a path following the line of the road will be found.

From this point the Northern Plain is seen to be spread out like a carpet, with the Point of Ayre at its tip. Behind this are the Scottish hills, and, in a more westerly direction, the Mourne mountains which 'schwape' down to the sea in Northern Ireland. These can be identified by the manner in which their skyline rises from right to left and then dips steeply. Underneath is Lezayre churchyard. By this time the top of Skyhill itself is get ting behind our left shoulder. If it is desired to climb this it is best to start up at a point where a wall runs down almost but not quite to the road, deciding to turn parallel to it instead. Follow up to the right of the wall and the rest is easy.

If Skyhill has been climbed, we can proceed along the top of the ridge in a southerly direction. If not, pursuing the road, a left-hand fork should be taken when reached. To aid identification there are the scanty re mains of a ruined cottage just beyond the fork, on the right. Follow this new track round to the left, make for the first and only clump of trees in sight, and when this is reached go on to a second which is little short of being the highest point in the near neighbourhood.

Here again there is a view to admire. From left to right in the east is the ridge which begins with the summit of North Barrule and passes on via slightly lesser heights to Claugh Ouyr (1,808 feet). Behind and to the right of this and just west of south of our vantage point is Snaefell, unmistakeable by reason of the electric-train terminus which can be distinctly seen. Further west are miles of rolling hills with the famous Sulby Glen behind them. All the other features of the landscape seen lower down are now visible to better advantage.

We return to the original track and pursue it to the right once more until a farm (which may be unoccupied) is attained. This looks right down into Glen Auldyn into which it is now necessary to descend. It is not very easy to describe the descent, for which there are two alternatives. One can either look for a path which leads down the left side of the square-shaped gully in front, or follow round to the right of this and pursue a track which zigzags easily down the hill. Either way, the bottom of the glen with its minor torrent is reached in an easy ten minutes.

By this torrent you may have my experience and meet a lady from a nearby farm who will tell you of the salmon she has seen, quite a big one, going upstream. As many as seventy five have been known to ascend the glen but very few are known to return. This may be the reason why further progress up the glen is heavily barred and why notices warning tresspassers to "Keep Out' appear regularly in the local paper.

Our way lies to the right, downstream. In a very short time the bridge over the water and the good road down the bottom of Glen Auldyn are met, while another mile brings us to the main Ramsey-Peel road once more. It may be preferred to return to Ramsey by the path through the fields already described in the walk which deals with the Three Glens. Once again, this is a walk for a morning or an afternoon. There is little hope of refreshment en route.

XI. TWO GLENS—BALLAGLASS AND MONA

THIS is another walk which can be done almost equally well either from Douglas or Ramsey, there being 'bus and electric train stops easily reached from either centre.

We begin, right away, with ten wonderful minutes down the wooded glen which many regard as the finest on the Island. The electric-railway company who own the glen have provided bridges and paths without spoiling the general effect. An attempt at description is hardly requisite. It is definitely a glen not to be missed. Emerging after ten minutes across a bridge a small cottage by a mill is reached where good teas may be obtained. If the rhododendron in the garden is not the largest in the island it is certainly a very large one.

The mill itself, which played a prominent part in one of Hall Caine's novels, is a few yards down the road toward the sea. Just before reaching it, turn up to the left and then right at the top. Hence it is about two miles of easy strolling to the Cornaa Beach; Glen Mona, up which we proceed on the re turn journey, comes into view on the right as we proceed. Ignore what seems to be the obvious route to the right, when reached, and keep left through a gate into a wood in which a number of fine trees are being slowly strang led by the growth of ivy, which is a pity seeing that five minutes' work on each tree every ten years would obviate the risk of this.

Once again the open is soon regained — indeed it is a feature of this as of other walks on the Island that so many different types of scenery are met with in quite a short space of time.

The wood can be left by an opening on the right in due time but the trees should be hugged on the way to a wooden bridge, a fairly wide one for these parts, across a fair sized stream. On its further side, make across the grass straight towards a boat-house over looking Port Cornaa, a nice little bay with a steep-ish shingle beach whence the telegraph cable to England enters the sea. It is a quiet and a pleasant spot. Sandwiches! Incidentally, there is no point in chasing up what appears to be a good path on the opposite side of the bay under the cliffs. It gets you no where.

Turning back, go up the road, through the gate on the left and along through the woods. Glen Mona, despite its name, is not one of the finest of Mona's glens but the woodland has its appeal, particularly in the spring. I believe that it is below this that I once saw the finest bluebells I have come across anywhere in the British Isles, but one has to be there at the right season of the year in order to verify this.

Out into the open, take the bridge on the right over the stream and go up the rough path straight in front past some cottages, when Glen Mona station is reached in five minutes, the whole round being easily done in two hours.

It may have been noticed that on the whole the time given for these walks is on the generous side. This is deliberate, for nothing can be more irritating than to find that the time given for an expedition is on the tight side with the result that the latter part of it has to be rushed. If something more strenuous is called for, this can be done by selecting two of the walks and joining them so as to make an outing for a full day. For example, this and the next walk to be covered may be undertaken successively by a little management.

Alternatively, if time is to spare, a short expedition can be made in the neighbourhood to Cashtyl-yn-Ard (better known locally as The Burial Place). This is reached in a quarter of an hour by making for a small but thick and conspicuous clump of trees standing alone on the skyline midway between the two glens. Enquiry may be made, if necessary, for Ballachrink Farm, a field away, which is marked on the map.

Cashtyl-yn-Ard is one of the most 'satisfying' sights on the Island and it is not in apt to refer to it as the Manx Stonehenge even if on close examination it turns out that the points of resemblance between the two are not striking. It is of comparatively recent discovery or, rather, restoration, and it is not, therefore, dealt with in some of the guide books. It should certainly be visited and the way back to the main road at Corrany will take only a few minutes.

XII. OVER THE HILLS FROM KIRK-MICHAEL BALLAUGH

THE nearest centre for this is Peel on the west coast, but Kirkmichael can be reached by steam train either from Douglas or Ram sey, or by 'bus from the latter only, and that not very frequently. It is not always wise to rely for information on local enquiry. For example, two separate inhabitants of Kirkmichael, asked how long it would take to walk over the hills to Ballaugh, could not say as 'they had never been up in the hills —two miles away!

Turn left on reaching the main road from the station and, passing the church on the left, take the second of two closely adjacent turns — to the right, there being another coming in from the left in between the two now in question. We go steadily up for an hour, land and sea opening up behind us as we go. St. Patrick's Isle, off Peel to the south, comes in to sight in due time. The deep cleft to the south is the upper part of Glen Wyllin.

The narrow road becomes a path higher up and winds along the near side of a stone wall, curving to the right as it mounts until, after we have left the wall, a wire fence bars our way. Turn up along this and to the left and a cairn comes into view almost at once, just before the top of the ridge is reached.

Here there is a stupendous view of the in terior of the north of the Island, the swelling rising to a tip on the left is Slieu Curn (1,153 feet). The depths which open into the North ern Plain after widening all the way down from a narrow cleft beneath our feet are those of Ballaugh Glen. The cleft itself is Glen Dhoo. Beyond, but hidden by the hills in the middle distance, are Sulby Glen and Druidale. Sulby is the best-known glen on the Island but I do not consider it as one of the most attractive from the point of view of the walker since its survey involves several miles of tramping along the road until that real gem, Tholt-y-Will, is attained.

Getting back to our cairn, if you want a really long tramp on top of what you have al ready done, turn right, following the left slopes of Slieu Faraghane (1,602 feet) the summit of which is a mile due south of where we are now standing. When level with this summit a track forks back to the left and leads down by the right of Slieu Dhoo (1,417 feet) either into the long length of Sulby Glen or, if the heights be held for another couple of miles, keeping to the left of Mount Karrin (why 'Mount' and not 'Slieu'?) (1,084 feet), down into the bottom end of Sulby Glen: the latter being the preferable alternative. In both cases you can count on having to do a full seven miles from the top before Sulby Glen station is reached.

Or, avoiding the turn back to Sulby, a couple of miles straight on will bring us on to a good road which winds down from the Snaefell massif to Kirkmichael—but it is a long, long way.

Going back yet again to our vantage-point near the cairn, we prefer to turn left here along the track towards a gate in the stone wall ahead and then on. The way is obscure and overgrown in places but you will not be far from it if you aim at a slight dip on the skyline. As you proceed, what appears to be quite a high and well-shaped mountain comes into sight to the east, but further progress will reveal that it is only our old friend, North Barrule, after all, for Snaefell will then have appeared with its station on the top and looking majestic from this angle.

We do not, after all, go down into Glen Ballaugh, for the track, becoming a road and then a grass lane, past a farm, keeps parallel to the glen and finally joins the main road at the western end of the village of Ballaugh, well under three hours from Kirkmichael. If time admits, a short visit might be made to the area known as the Curragh—or this may be made the object of a separate outing. Take an opening to the right just south of the station and follow on over the footpath for ten minutes. A few yards to the right and then another forward track leads close to Ballaterson where, in 1819, was discovered the great Irish elk now in Edinburgh museum. It was nine feet in length. Another specimen is in the Manx Museum.

The walkers of Manx are particularly fond of the Curragh, so different from the rest of the island and so near to nature. Fossils have been found there and all sorts of prehistoric relics.

There are wild flowers and wild birds, and the peat can be thirty feet deep, so goodness knows what further discoveries may be brought to light.

The return can be made by bearing back to the main road anywhere on the way to Sulby Glen station.

XIII. ROUND BRADDA HEAD

THIS makes a good first walk in the neigh bourhood of Port Erin, which, you may remember, was barred to visitors throughout the war owing to the fact that it was chosen as the place of internment of women and married couples of enemy origin.

Starting from, the middle of the promenade, bear right until passing through a gateway bearing the sign ' Bradda Glen'. We shall see little coves and bathing places below en route and the glen itself is well developed though rather artificially. Leaving it, we climb in a few minutes to the conspicuous Milner Tower (to use the classic phrase— You can't miss it'!). This was erected by a grateful seaside resort as a memorial to Milner 'The Safe Man' who lived in Port Erin and took a great interest in its development.

Examine the outlook from its summit. Below is the bay of Port Erin. Behind is the southern extremity of the Isle of Man known as the Mull Hills, rising gradually from the plain and then plunging steeply into the sea. In the middle distance is Cregneash, a characteristic Manx village, which we shall visit later. Beyond is the Island's satellite, the Calf, also to be inspected at closer range. To the east is a long stretch of flattish but much indented coast-line, beginning with Port St. Mary and passing on through Castletown and Derbyhaven, where the first races for the Derby Stakes were run long before the Blue Riband of the Turf was transferred to Epsom Downs.

We continue climbing coastwise along the edge of the beetling cliffs to the cairn on the top of Bradda Head itself whence, once more, a fine view is embraced, differing, however, substantially from that just seen from the Milner Tower, in that Port Erin is now masked, while the high cliffs and hills to the north, previously hidden, come into sight. The cliffs range towards Niarbyl and Cronk ny Irree-Laa already visited, and the swelling to the right is South Barrule.

It is indeed a steep descent to Fleshwick Bay and it is best and easiest to veer to the left as far as practicable. Turn right at the bottom and follow along the road towards Port Erin, turning right again when a narrower lane is reached at the end.

The entire circuit can be done comfortably in two hours and a half but it would be a sin to take less than double the time over a walk which is one of the finest on the Island.

XIV. MULL PENINSULA & CREGNEISH

IF your chosen centre is Douglas or somewhere else other than Port Erin or Port St. Mary you will probably prefer to devote at least one whole day of your holiday to a visit to the southern extremity of the Island, known as the Mull Peninsula. If so, this and the following walks should be treated as one, the inspection of Cregneish being regarded as a necessary side-show.

If, however, one of the adjacent resorts is the starting-place it is worth while to do the Peninsula in two separate instalments, be ginning as follows. Climb the hill rising from the centre of Port Erin in a south-westerly direction. A picturesque cottage on a bend, half-way up, houses the studio of William Hoggatt, R.I., the Island's most eminent painter. The road is running beside a tiny glen, the stream of which is later crossed by a primitive stone bridge. The glen and its streamlet disappear away to the right but the road leads on under the lee of Mull Hill (536 feet) to a small tarn, along the further edge of which a diverging path, is followed.

We are now leaving a particularly bad area for iron bedsteads. It would appear that at some period in the history of the Island the inhabitants must have risen as one man and decided to scrap all their iron bedsteads, pre sumably in favour of wooden ones, as a result of which they have used the discarded bed ends for fencing all over the place and no where more than in the Mull Peninsula.

A field is entered by crossing a stone stile. Turn right, through the farmyard, and strike across the fields diagonally towards the edge of the cliffs. With luck you may flush a wood cock and you will very likely set some rabbits scuttling. Here in the heather and the gorse we are indeed alone with nature, all the more so as most visitors keep to the other side of the Peninsula because there are to be found the best-known of its attractions—which we will visit later.

Descend the hill to jom the road which runs through the centre of the Island's ex tremity to end at the Sound, only 500 yards wide, which divides Man from his Calf. Do not be deceived into thinking that the Calf is here easy of access. Shoals, rocks and swift currents render the passage dangerous despite the short distance. In any case the Calf it self is not ordinarily open to visitors.

It should have taken an hour and a quarter to this point.

Whether we return via Spanish Head or the Chasms or leave them to another time, we must begin by going back along the road, which, like most of the roads on the Island, is terribly hard on shoe-leather, which reminds one that footwear should be stoutly soled and preferably nailed before entering on any series of walks on the Island. .

The short route back leads us up the road to what is the essentially Manx-like village of , much of which is actually an open air museum.

Its people are Manx of the Manx. Harry Kelly's Cottage, furnished in the old Manx style, should be inspected, as should a primi tive lathe and a hand-loom. There is also what is claimed to be the only thatched farm stead in the British Isles. The thatch is bound down with ropes weighted with stones against the force of the winter gales, much as in the west of Ireland. Indeed the whole district is reminiscent of that part of the world.

On leaving the 'museum' area turn left and, bearing right, you will find yourself back on the road by which Port Erin was originally left, the return from Cregneash taking half an hour.

For the second half of the exploration of the Mull Peninsula, we will start from Craigneash, easily reached either from Port Erin or Port St. Mary.

From Harry Kelly's Cottage, a tarmac road, marked on the map as a narrow track, runs south for a quarter of a mile, then you come into sight of a building below on which the word 'Chasms' is painted in white letters.

Here is a natural phenomenon worthy in its way, in the opinion of the writer, to rank with the famous Giants' Causeway. There is, of course, no actual resemblance between the two.

As the name implies, the Chasms consist of a series of crevasse-like rifts into which the cliffs in this small area have been split from top to toe. One theory is that this is due to subsidence, another that an earthquake was the cause. They are interesting to explore, but reasonable care is necessary for a false step could have disastrous consequences in some places. There is a lovely sunny grass plateau at the far end suitable for a rest, if one be needed thus early.

Returning to the cliff path, pursue this towards Spanish Head, the south-westerly extremity of the Island, so called because, according to tradition, a vessel of the Spanish Armada was wrecked upon the rocks beneath. The last stage of the approach to it lies by the path along the top of cliffs which mounts first to the summit of Black Head and then the topmost point of Spanish Head itself, not much more than a mile, as the crow flies, from the Chasms, although you will take not less than half an hour to cover the ground. .

The view from the top downwards is grand and exciting for there is a sheer drop of 300 (some say 400) feet into the sea. 'The cliffs in the vicinity assume all sorts of queer shapes and stratifications. Definitely this is one of the high-spots of the Island.

Return can be made by cutting across to the road referred to in the previous walk, but, preferably, by going back to the Chasms and then carrying on along a lane, reached through a gate, which later winds its stony way down to the right and back to civilization.

If returning to Port Erin you can turn left, just beyond a chapel, to Glendown and then left again. If to Port St. Mary, keep right across the top of pretty little Purwick Bay, when Port St. Mary is entered in a matter of minutes. I should allow between two and three hours. :

XV. ROUND ABOUT SANTON

THIS is part of the Island and of the coast line not much frequented by the visitor and, truth to tell, there is nothing of sensation about it although it is pleasant enough.

A steam train or 'bus will take you to Santon half-way between Douglas and Castletown.

If leaving the train, follow along the right hand of the track towards Douglas, turn right at the road, and then pursue this under a beautiful avenue of trees. Left, right, as the opportunity admits, brings us into Glen Greenaugh and down to the sea at Port Greenaugh in a mile and a half from the station.

Here you must pick your way across the beach to ascend the low cliffs to the left, avoiding seaweed and rusty tin cans as necessary. The way along the top through one field after another may occasionally be barred by barbed wire but it will generally be found that someone has been there before us, and where he has worked his way through we can follow.

This digression will, we hope, have taken us to the point at which we make our exit from the fields on to a rough path along the cliff and, if there is any sun about, we shall get it here. Soon a small U-shaped bay is reached into which we clamber down, immediately to climb up the other side. This should be about an hour from Santon station.

Soon after, another opening, Cass-na-Hawin, comes into the picture, the mouth of the river and glen of Santon Burn.

For the benefit of walking geologists and for what it is worth, we are informed that it is here that 'the character of the coast-line south wards changes from slate rocks to carboniferous limestone'.

Whatever the effect of this may be upon the reader, the fact remains that it is now desirable to turn inland lest you get on to forbidden ground on the Ronaldsway airport which lies ahead.

According to T. E. Brown, Santon Glen while 'one of the least known is undoubtedly one of the most picturesque and romantic of the Manx coast glens', but this cannot here be confirmed as we have not tried it. So instead, we follow along its edge inland, making for an unmistakeable white farmhouse. Thence follow farm lanes bearing left as necessary but aiming at the tip of South Barrule on the horizon in the distance. This will bring us out on the main road not far either from Santon or from the village of Ballasalla if it is preferred to pick up transport at the latter place. The last time I was there I saw my train go by, went on to the main road, picked up a lift in a passing lorry and caught up with my train at Castletown. Allow two hours for this walk.

XVI. A SHORT WALK FROM PORT ERIN

EVERYONE should see the biological station at Port Erin where they study marine flora and fauna and hatch millions of plaice and lobster annually for eventual transference to the sea. The frescoes on the walls above the tanks in the aquarium were painted by internees during the war. After the visit to the station walk up the zigzag path which leaves the level just beside the Bay Hotel. Behind the right-hand of the two houses at the top is a field gate.

Cross the field diagonally to get over the wall in the left-hand corner and then follow this to the right until a line of gorse bushes breaks away to the left. When a wall is reached at the end of this take care to cross it so as to come down on the inner side of the wall beyond, or else you will have a second obstacle to surmount.

All this leads to a lonely, broken part of the Mull Hills in exploring whose cliffs and coves a lazy morning can be spent.

When time is up, the run down from Cregneash with which we are already familiar, is close handy.

XVII. UP LHIATTEE-NY-BEINNEE

THIS is the jaw-breaking name of the highest point of the tremendous cliffs which overhang the coast immediately north of Fleshwick Bay, the culminating one of a seven-mile walk affording extensive views of the whole of the south of the Island, and a very good walk it is.

Bus or train to Colby, either from Douglas or from one of the ports. Get off not at Colby itself but at a turning half a mile west where there is a garage on the corner and also a public telephone box. Practically opposite is a tarmac road, which, passing a quarry, soon becomes a farm-track, running due north. Keep on through the first gate at the far end, but, short of the second, bear left along the hedge. Then turn right again and across the fields, aiming at the top of Cronk-ny-Irree-Laa, conspicuously the highest point ahead. We are rising all the time so that the landscape behind is opening up.

Over the stile at the far left-hand corner and we are on to a good road for a few minutes, having passed within a few yards of a circle of prehistoric stones. We then take care to turn uphill sharp left just before another road comes in from the right, which last is the direct road to Colby proper.

Right, left, right, along the ensuing tracks past Kirkhill Farm and up across the width of a field to a rough, overgrown path which runs from north to south parallel to the coast but on the near side of Lhiattee-ny-Beinnee (987 feet).

It is just possible to go straight up the slope to the top but much easier to start left and make a wide sweep round to the right, picking your way up the most gradual part of the rise.

There is an immense view once the height is gained although the lie of the land is not such as to admit of seeing all the 1,000 feet practically sheer down to the sea's edge.

Cronk-ny-Irree-Laa is two miles to the north, South Barrule twice as far to the north east, all the south side of the Island up to ten miles away, with the Mull Hills slightly west of south. The circle is completed by the mass of Bradda Head pitching straight down into Fleshwick Bay. It is extremely unlikely you will meet another living creature in these parts except for the odd sheep.

For the return, make for the cairn on the next rise to the south and then for the slight dip beyond in the same direction. Take care not to be tempted by any path or track to the left which would not only bring you down to the road again but add to the length and reduce the interest of the rest of the journey. When Port Erin comes into sight, far away and below, go straight for it and a by-road, lined with occasional farms and cottages, will be caught up with, which takes us down to Bradda Mooar and so to journey's end.

Total time: up to three hours.

XVIII. UP SNAEFELL

IT has been deemed well to reserve to the last the ascent of the monarch of the Island — Snaefell — the summit of which, despite the fact that it is only 2,034 feet above the sea, commands a view which is unique in the British Isles. It has been said that he who stands upon the cairn which marks its highest point dominates no fewer than seven kingdoms, as follows: England, Scotland, Ireland, and Wales, the Isle of Man, and those of the Heavens above and of the nether regions below. It would be interesting to know on how many days in an average year the first four are visible at one and the same time.

It may be mentioned that Scotland, at its nearest point, is only thirty miles away, while England is but thirty-eight. Slieve Donard, the highest of the Mourne Mountains, is sixty miles off, and Snowdon eighty.

The view over the Island itself begins with North Barrule, to the right of which Maughold Head peeps out. The entire length of the valley running down to Laxey is visible to the east, and, further south, Clay Head and Douglas Head, although Douglas itself is not in sight. You may see the square tower of King William's College with Derbyhaven and Castle town close by. And then, at the far end of the Island, come the Mull Hills and the Calf. South Barrule and Cronk-ny-Irree-Laa look like a couple of twins, seen from our vantage point. Peel is hidden but Corrin's Folly on Peel Hill beyond can easily be distinguished. Swinging west, we come to the hills in the Kirkmichael district and it may be possible to identify the cairn on Slieu Carn, around which we pivoted in an earlier walk. The tower of Jurby church is a conspicuous landmark in the middle left of the Northern Plain and can be spotted by following with the eye along the line made by Glen Auldyn. The last item in this bird's-eye circuit of the Island is Ramsey, but to see this you will have to go forward 200 yards to another stand-point. Which brings us back to North Barrule.

All this does not mean that the climbing of Snaefell calls for anything remarkable. It must, in fact, be admitted that a high proportion of the Island's mountaineers 'do' its highest peak by taking a ride on a branch line of the electric railway, which breaks off from the main line at Laxey and climbs steadily all the way up a gra dient of one-in-twelve. The terminus at the top has already been referred to as visible from many distant parts of the north of the Island.

Of the several routes up Snaefell on foot we will confine ourselves to two, plus possible variations.

The shortest way up from the level begins from Laxey. Passing the Great Wheel, zigzag up to Agneash, follow a track alongside the mill-race as far as a lead-mine, a mile distant, and then scramble up for another half-mile to the mountain road, whence there will be about 800 feet to climb. It is not very difficult to make straight for the top and any of several paths may be picked up, but if it be desired to do it the easy way it is best to turn left along the road to the Bungalow, at the cross-roads, and then ascend the most gradual part of the slope.

From Ramsey the simplest route is to follow the mountain road for six miles until the lowest point in a straight line between Snaefell and Clagh-Ouyr is reached. The Guthrie memorial in memory of a famous rider in the Tourist Trophy Races is passed. en route.

At the point referred to just above go ahead straight up Snaefell instead of following the road as it bends to the left.

Most walkers will, however, prefer to climb North Barrule to begin with, and to carry on along the ridge to the top of Clagh-Ouyr, three miles away, with extensive views all the way. Hence onwards it is a case of each walker for himself—down and up along the bee-line to Snaefell. Yet another possibility, rather long er in distance but much less arduous, is to follow up the Old Douglas Road, after reaching it from Ramsey via Ballure Glen. There is a steady rise under the lee of North Barrule along a wild open valley to Park Llewellyn, just 1,000 feet above sea-level. The track continues on and upward and, by keeping forward, the mountain road is eventually reached.

It need hardly be said of the above methods of ascent that they can equally be used for the return journey. Similarly the ways down to follow can be pursued in the reverse direction if more convenient. One other thing to men tion is that there is not the same possibility of getting lost in the wrong valley that there is in some other mountain districts.

A most attractive return route is via Injebreck. A mile below The Bungalow, on the road to Douglas, a road turns sharp back to the right and encircles the northern slopes of the hill called on the map Beinn-y-Phott (1,720 feet) or, more simply, Pen-y-Pot. This is a fine bit of country, the road itself rising above 1,400 feet. Then, just before the road bears left, a rougher track makes off, still further left, and goes down to Injebreck.

Injebreck is a wooded recess tucked away in the very heart of the Island. It is eight miles from Douglas and the lie of the land is such that it is not easy to get back to the capital by a route which is genuinely 'cross-country.'So, on the whole, it is best to walk down the road for three miles as far as Baldwin, pick up a 'bus there and call it a day. The distance between the top of Snaefell and Baldwin is between seven and eight miles. If there be no convenient 'bus from Baldwin the long tramp home can be slightly reduced by turning right at Strang for Union Mills, half a mile on, whence there is a much wider choice of conveyances than at Baldwin.

We have left to the end the way down from Snaefell via Sulby Glen, the largest, and, it may be, the best-known glen in the whole of the Island.

This, save for the initial scramble down 1,000 feet in a mile, is a road walk all the way, except for the short cut through Tholt-y-Will. From the top to Sulby Glen station at the far end of the glen is a long five miles.

Tholt-y-Will is a delightful little glen, a deep tree-lined cleft in the hills, reached by turning into its top entrance on the right about half an hour after Snaefell is left behind. For the rest, Sulby Glen is much like one of the dales of Lakeland. There is a possible diversion to see the Cluggid Falls at the head of the stream which tumbles into the Sulby river opposite to steep Mount Karrin on the left, and two miles below the exit from Tholt-y Will.

Further on are cottages where tea or the like may be enjoyed, always provided that the time-table does not make it necessary to press on to the station. When you pass the woollen mills you have only half a mile to go, or four altogether from Tholt-y-Will.

Two hours will be enough to get down from the top of Snaefell.