Manx Tailless Cat

[From Isle of Man by John Quine, 1911]

In its natural history-the mammals, reptiles, birds that are found on the island, the fish found in its rivers and in the surrounding sea, the plants indigenous to its soil-the Isle of Man does not differ very much from the surrounding countries of Great Britain and Ireland; the main difference being that the list is smaller.

Going back to the time when the island was connected with Great Britain, and Great Britain with the Continent of Europe, there remains a trace of the life of that period in two perfect specimens of the great Irish elk, which have been found in blue clay under the peat-formation of a later period.

In the Danish period red deer were numerous on the island, and existed down to the seventeenth century. The old breed of cattle was black, akin to the Galloway breed ; and the Manx pony was also of a variety similar to the Galloway pony. A peculiar breed of sheep called " loaghtyn," with a yellowish-brown wool of a fine and very durable quality, was once the common or the only sort : but now it exists only in a few small flocks kept for reasons of sentiment. Wild pigs, or purrs, once wandered on the uplands, but have long ago become extinct. Goats were once numerous, and in some cases existed in a feral state: indeed there are still a few on the inaccessible steeps on the western side of Cronk-na-Irey-Lhaa.

The avifauna of Man differs widely from that of the adjacent part of England, and agrees much more closely with that of Ireland, and with that of the north western extremities of Wales.

Most of the commoner birds found both in Great Britain and Ireland occur in somewhat the same relative abundance. The rook, 120 years ago said to have one rookery only, is now very abundant, and the blue-tit, 200 years ago unknown, is now plentiful. The song thrush is rather a winter than a summer bird. The common mistle-thrush nests on rocks and walls as well as in trees. The stonechat is a resident and characteristic species, but the whinchat is known only on passage. There are few records of the barn owl. The red grouse is a recent re-introduction. The black-headed gull and redshank are found through almost the whole year, the former abundantly, but leave at breeding time. The heron, Comparatively common, seems not to nest now.

Species characteristic of uplands and hill-streams are rather scarce. The curlew nests here and there, the snipe more frequently; but the golden plover and dunlin are not known to breed, and the common sandpiper, conspicuous on migration, does so rarely. The dipper, twite, and grey wagtail, too, are also infrequent breeders.

The stock dove has recently become well established round the coast, and the woodcock nests in the young plantations.

If we turn to the common British summer migrants the separation of Man becomes more marked. The willow warbler and whitethroat are the commonest of their kind, the sedge and grasshopper warblers fairly common. Swallows are scarcer than on the mainland, and the house martin is infrequent and often a rock breeder. The swift and nightjar are scarce, but the cuckoo and corncrake common. The chiffchaff, wood warbler, and spotted flycatcher occur sparingly. The wheatear, abundant on migration, does not breed numerously. Most of these have a similar status in Anglesey and west Carnarvonshire. In the distribution of winter immigrants Man seems to differ less, though the estuary-loving species of ducks, geese, and waders naturally do not appear in large numbers.

Species rare or absent in Ireland are often scarce or wanting in Man. Such are the woodpecker, tawny owl, jay, tree pipit, pied flycatcher, marsh tit, red-backed shrike, redstart, garden warbler, blackcap, Ray's wagtail. This group of non-Irish British birds shows much the same distribution in Man and north-west Wales. The most conspicuous example of the correspondence with Ireland, and divergence from England, of Manx bird-life, is perhaps the distribution of the black and hooded crows, the former absent, the latter breeding commonly in Man.

Cliff -breeding birds abound, though the rock pigeon, curiously enough, seems to be extinct. The dominant species is the herring gull, the lesser black-backed gull is less common. The kittiwake has two settlements ; in a few localities guillemots and puffins breed; razorbills occur more generally. The black guillemot has some small colonies. The cormorant breeds sparingly, the shag abundantly. The arctic and lesser terns have each a colony.

There are some interesting survivals. Eagles (probably white-tailed) became extinct some 70 years ago, and the Manx shearwater no longer breeds. But we have still the chough, and the peregrine and raven have a number of stations. Among the few rarer British species which have occurred are the golden oriole, snowy owl, Greenland falcon, and Pallas's sand-grouse. The entire number of species recorded as occurring on the island is about 190, and of these some 93 breed with us.

No fossil remains of birds have been found.

There are three Acts of Tynwald affecting birds, viz. the Sea-gull Preservation Act, 1867 ; the Game Act, 1882 ; and the Wild Birds Protection Act, 1887. In old statutes the falcons and herons, which bred on the cliffs, were rigorously protected. Hawking was a favourite sport, and many falcons were obtained from the island for hawking in England. The Stanleys held the island on the tenure of duly presenting a cast of falcons to the Kings of England at their coronation, and this usage was observed even by the Dukes of Athol down to the nineteenth century.

All the Manx rivers have trout, except the Laxey and Foxdale, which are spoiled by the lead washings of Laxey and Foxdale mines. Salmon and white trout come up the larger rivers, especially the Douglas and Sulby. In recent years the rivers have been stocked with trout; and there is excellent fishing, especially in the tributary streams high up towards the mountains, and in the reservoirs of the Douglas Corporation on the Douglas and Groudle Rivers.

The flora of the Isle of Man is interesting; the number of species probably does not exceed 500, but of the commoner species the abundance is remarkable, and almost every group is well represented, the country possessing so many kinds of habitat. Lying as it does nearly in the centre of the British Isles the Isle of Man possesses a flora closely similar to that of the surrounding district, north Ireland, Galloway, Cumberland and north Wales. Considering the height of the mountains, it is perhaps curious that alpine and sub-alpine plants are almost entirely absent. Rare or non-existent, too, are most of the plants which love the chalk. On the other hand one of the most striking features is the abundance and luxuriance of the plants of the rocky and sandy sea-shore. It will further be noted that, owing to the mildness of the climate and the rarity of severe frosts, garden plants such as the myrtle, fuchsia, clianthus, geranium, etc., grow luxuriantly in the open without any protection during the winter months.

A conspicuous feature of any Manx landscape is the gorse, one species of which (Ulex europaeus) clothes almost every hedge side with golden blossom in the spring, and fills the air with its scent ; while another (U. nanus) covers the hill-sides and the waste ground at the Point of Ayre in the autumn. As an effective background to the gorse is the purple ling and two species of heath (Erica cinerea and E. tetralix). On the central mountains is found also the crowberry (Empetrum nigrum).

Plants specially abundant by the waysides are the pepperworts (Lepidium campestre and L. Smithii), the latter being the more common variety ; Viola tricolor, with several sub-species in the sandy ground of the north ; the milkwort (Polygala vulgaris) ; the pretty stitchwort (Stellaria holostea) ; several kinds of St John's wort (Hypericum) ; a very large number of species of Rubus (bramble) which grow with unusual luxuriance ; the cinquefoil (Potentilla tormentilla) ; the pennywort (Cotyledon umbilicus), which attains to a remarkable size ; a number of umbellifers ; the yellow bedstraw (Galium verum) ; and many others too familiar to call for special mention.

In the mountain glens may be found the meadow sweet ; golden saxifrage (Chrysoplenium) ; the round-leaved sundew (Drosera rotundifolia) ; enchanter's nightshade (Circaea) ; marsh valerian ; golden rod, with a variety Solidago cambrica ; dry-leaved campanula ; bog pimpernel; common butterwort and pale butterwort (Pinguicula lusitanica) ; and the lesser skull-cap (Scutellaria minor).

The Curragh district to the north-west of the island is particularly rich in characteristic plants, such as loosestrife, forget-me-not, bog-myrtle, bog asphodel, the branched bur-reed, water plantains (Aisma plantago and A. ranunculoides), and others.

The sea cliffs are covered in the spring with Scilla verna ; other interesting plants of the sea-shore being the Isle of Man cabbage (Brassica Monensis)-which still grows north of Ramsey, where it was first discovered by Ray in 1677, and in other parts of the northern shores-the sea poppy, several varieties of scurvy-grass, seakale, the tree mallow, sea stork's-bill, sea holly, samphire, thrift, and a large number of the Natural Order Chenopodiaceae.

The following also seem worthy of notice either for their rarity or for other reasons ; the whorled caraway (Carum verticillatum) occurs occasionally in damp meadows ; the cowslip has frequently appeared and continued for two or three years but has never proved permanent ; centaury is well known as a remedy for the "King's Evil"; henbane and the true nightshade are found, but rarely ; the great mullein (Verbascum Thapsus) is perhaps wild at the mouth of Sulby Glen ; cow wheat (Melampyrum pratense, var. montanum) appeared some years ago on the summit of South Barule, and has continued in the same locality since, its nearest habitat being the Mourne mountains in Ireland, from which it was no doubt brought by birds ; the lesser twayblade (Listera cordata) is reported from the Dhoon and red spur valerian appears to be naturalised on the cliffs above Douglas. There are not many species of orchis. Succory occurs periodically, probably imported with corn-seed, but is not permanent ; and other escapes are occasionally found.

The various glens produce great abundance of ferns. Maidenhair was unfortunately extirpated some years ago by over-zealous tourists, and the Osmunda, once the glory of the Curragh, is threatened with a similar fate. Harts tongue is comparatively rare, and does not attain a large size ; adder's tongue (Ophioglossum vulgatum) is found in a few localities.

Manx Tailless Cat

A certain notoriety has been attained by the Manx tailless cat. As no mention of it occurs in the various books descriptive of the island written in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, it is generally believed not to be indigenous, but is supposed to be descended from a tailless variety brought from the East Indies. The Manx cat is much less common on the island than would appear from many recent accounts of the island : and the frequency of its occurrence has been much exaggerated. The tailless poultry occasionally seen are also doubtless derived from a foreign breed ; no one, at least, seriously regarding the breed as indigenous.

If we omit indentations, the Manx coast is more or less quadrilateral, the longest or western side of 33 miles lying north-east from Calf Sound to the Point of Ayre ; the shortest or southern from the Calf due east to Langness Point, seven miles; the eastern from Langness north-east to Maughold Head, 22 miles; and the north-eastern from Maughold Head to the Point of Ayre, eight miles. The whole length is thus 70 miles, but taking count of in dentations, the actual coast-line is over 80 miles.

The indentations are numerous but not deep, the western coast being the least indented and the southern end of the island a succession of definitely formed bays. Out of twelve bays around the whole coast, five are at the southern end: and this district, forming the ancient Sheading of Rushen, may have derived its name "Rushen" from the plural of the Celtic word ros, a promontory, " the promontories."

The Calf of Man is off the south-west corner of the island, beyond the Sound, which at its narrowest is about half-a-mile wide, broken here by the grass-capped islet of Kitterland. The coast hereabouts, on both sides of the Sound, is very precipitous. The high cliffs begin from Perwick, a bay near Port St Mary, where the limestone ends and the jagged slate cliffs emerge from underneath it. This slaty coast extends all the way round to Peel, nearly midway on the western coast.

Two miles north from the Sound is Port Erin Bay, passing in between lofty precipices, and expanding in land-locked tranquillity to a beautiful shore, around which is the modern watering-place of Port Erin. From its recess one sees the sunsets behind the Mourne mountains in Ireland. Immediately north of Port Erin, around Bradda Hill, is Fleshwick Bay, with an uninhabited shore, overhung by the dizzy crags of Bradda and Cronk-na Irey-Lhaa. From Perwick round to Fleshwick may be said to be by far the finest part of the coast scenery of the island.

Bradda Head, Port Erin

There are no real indentations on the western coast north of Fleshwick, except at the Niarbyl and at Peel. The Niarbyl (or Tail) is four miles from Fleshwick, and consists of a tidal reef striking out a quarter of a mile from the cliffs, and sheltering a shingly strand with a group of fishermen's cottages. Peel is five miles further on. Peel Bay is sheltered from all westerly winds by St Patrick's Isle, an outlier of Knockaloe Hill, which is of the same formation as the main mountain range, but lying parallel to it. The sea front of the highest part of this hill is called Contrary Head, and derives its name from the fact that the tidal floods coming up channel between Wales and Ireland, and down channel between Scotland and Ireland, meet off this head, and in bad weather cause an ugly cross sea. St Patrick's Isle was joined to the end of Knockaloe Hill by a causeway about a century ago, in order to protect Peel harbour. Peel Bay, within St Patrick's Isle, has been formed by a tidal bore scouring away the sands and gravels here resting on the junction of the Red Sandstone formation and the underlying slate, which on the western side of the harbour rises into the high ridge of Knockaloe Hill.

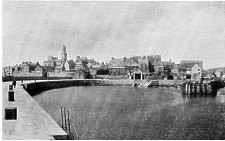

Peel, looking East from Knockaloe Hill

Peel is in some respects the most picturesque town of the Isle of Man. The houses are mainly built of red sandstone, as is the cathedral on St Patrick's Isle, the Round Tower and ruined church of St Patrick, and a considerable part of the Castle. The district, as seen from the sea, is quite bare of timber ; and the cultivated hill-sides have a look of sterile and wind-swept hardness. Every aspect of the town and its background suggest the idea of a sea-faring race, to whom the sea is the true field of their occupation.

The port had once an extensive sea trade, in smuggling, in fishing, and in coasting; the latter including the carrying of fish to continental ports from the Baltic to the Mediterranean, of oranges and other fruits to the English market, and of barley from the Baltic. In the course of time all these activities have passed away, the only surviving sea industry being the fishery, and that in a much decayed state.

For two miles or so north from Peel the Red Sandstone cliffs, which show a slight dip of the strata seawards, have many sea-worn caves and very beautiful beaches, on which are found garnets and other pebbles. Beyond the Red Sandstone are some altered and igneous rocks which are also honeycombed into caves and natural arches. On these rocks rest masses of clay forming cliffs that have at a distance the appearance of a formation of rock.

Five miles from Peel the hills recede from the coast, and the sea brows begin to be of sand and gravel, with a level sandy shore. The coast is of this character for the rest of the way round the northern end of the island to the foot of North Barule in Ramsey Bay.

The coast of sandy brows and level shore is broken by four V-shaped notches in the parish of Kirk Michael, where the glens open on the shore, and their streams enter the sea. There is one river mouth on the shore of Ballaugh, another between Ballaugh and Jurby, another between Jurby and Kirk Andreas, the former flowing from the hills, the two latter draining the Curraghs of Ballaugh and of Lezayre.

Beginning from the Sound, of which we have already spoken, it is a bare mile to Spanish Head. Between this and Perwick a detached stack marks the locality of the Chasms, which are on the landward side of the cliff face, and parallel to it. There is also a detached Stack called "the Eye" at the south end of the Calf. All this coast is the haunt of innumerable sea-birds. From Spanish Head the reach of five miles east to Scarlett Stack is Poolvash Bay of which Port St Mary Bay is an inlet. From Scarlett Stack to Langness Point is Castletown Bay.

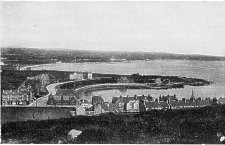

Port St Mary

Langness is a T-shaped peninsula, a mile and a half long, parallel to the main direction of the island, Castletown Bay, open to the south-west, being on one side of the isthmus, and Derbyhaven Bay, open to the north-east, on the other. Both Port St Mary and Castletown bays, in addition to having an aspect open to the prevailing south west winds, are shallow and rocky. Derbyhaven Bay has excellent anchorage and a different aspect, and in the days when the trade of the Irish Sea was carried on exclusively by sailing craft it was a favourite shelter for windbound vessels. The steam coasters now used in this trade very rarely need to avail themselves of its shelter.

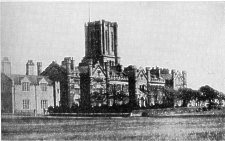

King William's College, Castletown

Port St Mary, on the western side of its bay, has a good breakwater and tidal harbour. The town is built of grey limestone, is very picturesque, and a favourite resort of marine painters. The country seen from the sea, however, is bare of timber. The town has in recent years become a favourite visiting resort, and has grown in population and become more modern in the style of its domestic architecture. The chief attraction of the place is its fine coast scenery in one direction, and the long reaches of accessible shore eastward around the bay. Castletown is also built of grey limestone, with a good harbour under the walls of Castle Rushen. It has never been a port of much trade, by reason of the shallowness and rockiness of the bay. But as the former capital of the island, the residence of the Lieutenant-Governor and the principal officials, and the seat of legislation it has the air of a small county town. Since the establishment of King William's College, the town has also become a place of residence for families taking advantage of the educational opportunities offered by the college. Castletown was the seat of the Kings of Man before 1265, and the centre of administration of the various Lords of Man subsequent to that date. Castle Rushen, in perfect preservation, is on the west bank of the Silverburn where it forms the harbour. There is also the site of a more ancient stronghold on the east bank.

Castletown

The tidal bore in Castletown Bay has eroded the deposits of sand and clay at the head of the bay and along the isthmus between Castletown Bay and Derbyhaven Bay, and this action of the sea is still going on.

Langness, an outlier of the slate formation cropping out on the seaward side of the limestone beds, is of low elevation, and naturally on that account was especially dangerous to shipping in the days before lighthouses and fog-signals : in past centuries it has been the scene of innumerable wrecks, especially of vessels coming up channel to Liverpool. The north-east horn of Langness is an islet of five acres, called St Michael's Isle from a ruined twelfth century chapel still standing there ; but more commonly Fort Island, from a round fort built by the Earl of Derby when he held the Isle of Man against the Parliament (1644-51). The islet is now connected by a causeway to Langness ; and the isthmus, once the race-course in the days of the Stanley Lords of Man, is now a golf links.

Derbyhaven was formerly Ronaldsway, or the Landing Place of Reginald : and this name is still attached to a large mansion house and estate on the inner shore. It was the seat of William Christian, Captain-General of the Manx Militia, who surrendered the island to the Parliament in 1651 ; and in 1662, after the Restoration, was shot as a traitor on Hango Hill, a knoll on the shore of Castletown Bay.

From Fort Island it is three miles to Santon Head ; and in this reach are several minor indentations, viz. the estuary of Santon Burn, Saltrick, and Greenwick. From Santon Head to Douglas Head is four miles, and in this reach is Port Soderick, which is not a port, but a picturesque strand and favourite resort for boating excursions from Douglas.

Douglas Bay is just two miles across, and is well protected from south-west winds by Douglas Head. Within the shelter of the head is a large tidal harbour on the estuary of the Douglas river, and an outer harbour protected by breakwater and piers. The crescent of Douglas Bay is singularly beautiful. The town, with a population of 21,000, is built on slopes and high levels, and extends around the curve of the bay.

Midway of the curve is Castle Mona, built in 1820 by the Duke of Athol, the last of the Lords of Man, who ended by selling his feudal rights to the Crown of England. In the bay is a rocky islet called Conister, with a tower erected by Sir William Hillary, the founder of the National Lifeboat Institution, whose house on the slopes of Douglas Head still exists as an hotel.

Douglas is the principal port of the island for general trade and for the trawling industry, but is above all a watering-place to which nearly half a million people resort during the summer season, mainly from the north of England manufacturing districts. For this excursion traffic are engaged the finest and fastest channel steamers afloat. The offices of the Insular Government, the Legislative Chambers, the Gaol, and the Record Office are now in Douglas; that is to say the seat of Government has been removed from Castletown, the former capital. The residence of the Lieutenant-Governor was formerly at Castletown ; but this also was transferred to a new Government House, on the high ground behind Douglas and overlooking the bay.

Beyond Douglas the coast stands out very bold for four miles, broken only by the little indentation of Groudle. At Clay Head, four and a half miles from Douglas Head, the coast recedes into the two-mile loop of Laxey Bay. At the south corner is Garwick, a boating strand; and at the north corner Laxey harbour, used mainly by vessels loading and unloading for Laxey mines, two miles higher up the valley.

From Laxey to Maughold Head, a reach of nearly six miles, the coast is again very bold, with little bights at the Dhoon, Corna, and Port Moar-landing places for boating parties, but with neither pier nor inhabitant. Maughold Head is the rounded knob of a hill spur striking east from North Barule, its summit 373 feet above the sea, and the cliff face a sheer precipice of 200 feet. Here the coast bends sharply, and the north-eastern end of the island is seen to be a concave, the line of eight miles from Maughold Head to the Point of Ayre marking the north-eastern side of our island quadrilateral.

From Maughold Head to Ramsey the coast is rocky. Ramsey bay has excellent anchorage. Queen Victoria and King Edward VII made Ramsey their landing place when visiting the island, and the Channel Fleet has anchored here on several occasions. There is a consider able trade from the port in the export of agricultural produce and of ore from Foxdale mine. The town is beautifully situated at the foot of North Barule, which dominates the bay and the whole northern district between Maughold and Kirk Bride. On the sea horizon are visible the whole range of the Cumberland mountains and a great part of the highlands of Galloway from Criffel on the Solway westwards to Cairnsmuir at the head of Wigtown Bay ; while over the northern plain may be seen the further extension of the Scotch land as far as the Mull of Galloway. From Ramsey to the Point of Ayre the coast shows a scarp of sandy brows and a margin of sandy shore.

It may be noted that along the rocky coast from the south-west corner of the island to Laxey there are nine indentations with names terminating in -wick or -ick (vik = creek), pointing to the Scandinavian period and the use of the Norse language.

On the rocky sea-walls and on the profiles of the headlands the geologist is able to trace former sea-levels, viz. at a height of from 12 to 20 feet above the existing level, at a height of about 60 feet, of 10o feet, and in fainter traces other older levels of still greater altitude, the latter being traceable inland along the sides of the glens. On the sandy brows of the northern plain, and in all the larger bays may also be seen the results of sea erosion.

The loom of the Manx mountains and headlands is generally visible at a distance, whatever be the direction from which the island is approached, and thus the coast of the island is less dangerous to shipping than a coast with low-lying seaboard. With the exception of Langness at the south-east and the Point of Ayre in the north, all the Manx seaboard is high. There are no shoals except the Bahama Bank five miles off Maughold Head, and some other shoals to seaward of the Bahama and off the Point of Ayre, but out of the track of ordinary navigation. Between the Bahama Bank and Maughold Head there is a broad channel of deep water. There are shoals off the Point of Ayre, connected with the Bahama Bank ; but here also a safe channel exists around the Point itself

.

Old Lighthouses on the Calf

Before the days of lighthouses and fog-signals however, the island, from its position in the midst of the Irish Sea, had its dangers, especially for vessels coming up channel to Liverpool, and for craft engaged in the cross-channel trade between Ireland and the north-western ports of England. Langness has seen innumerable wrecks. But in the annals of the island there is a singular absence of such tales of wreckers as we find associated with Cornwall and Brittany. The old safeguards of the southern end of the island were two lighthouses on the Calf of Man, now disused but still standing. Also on Langness there still stands an old landmark tower. Between 1870 and 1880 a new lighthouse of the Eddystone type, 122 feet above the sea, flashing white every 30 seconds, and visible at a distance of 16 miles, was erected on the Chickens, a rock a mile south-west of the Calf. Later a lighthouse was erected on Langness nine miles due east, with light flashing white every five seconds, and visible at 14. miles. These lighthouses have also fog-signals : the Chickens a detonator and Langness a steam syren. Since the erection of these two southern lights, wrecks on the coast may be said to be a thing of the past.

Douglas- Lighthouse

Douglas Head lighthouse has also a high-power light, 104 feet above the sea, flashing six times in every alternate half-minute and visible at 14 miles; and there is a fog signal, like that of Langness a syren worked by steam. Each of these has its distinctive note, especially necessary to the regular daily steamers between Douglas and Liverpool. In the offing of Langness the three magnificent lights of the Chickens, Langness, and Douglas Head are all visible; and whether in bad weather or in fog the neigh bourhood of this coast involves very little danger.

Port Erin, Port St Mary, and Castletown have harbour lights for vessels making these ports. The Sound, between Spanish Head and the Calf of Man, is dangerous only to vessels embayed, and to small craft attempting the passage when the tide is setting through it, for the latter, which breaks into two streams on Kitterland islet, sometimes runs at the rate of i 0 knots an hour. A reef called Thousla, marked by a small beacon and lying on the Calf side of the strait, is also a danger point. The dangers of the Sound are so well known, however, that all the craft entering it are piloted by boatmen acquainted with local circumstances of coast and tides.

Within Douglas Head, on which the lighthouse stands, are the Battery Pier and Victoria Pier lights, between which is the harbour light, used only by vessels making for the port anchorage, or entering the harbour. Laxey has also a harbour light. Beyond that there is no other on the east coast around to Ramsey; but five miles off Maughold Head is the Bahama lightship, which is an chored in 1 1 fathoms of water, and shifts its position with the drifts of the flood and ebb tides. Besides its light, flashing twice in quick succession every half-minute, the lightship has a fog syren; and there is also a buoy to mark the limit of the shoal.

Outside the Bahama bank is King William's Bank, so called from the historical incident of some ships of the expedition of William III to Londonderry in 16g0 touching ground on the shoal at low tide. It is merely marked by a buoy. About midway between Maughold Head and St Bee's Head in Cumberland, or 14 miles from each coast, is the Shumakite Bank, not dangerous to navigation. All courses round the northern end of the island are set by the Bahama lightship and the Point of Ayre light.

Ramsey has three lights, two on the north and south piers of the harbour, and one on the low-water landing-pier. The Point of Ayre lighthouse stands near the end of the low spit in which the Ayre terminates. The light is 106 feet above the sea. It flashes red and white alter nately, and is visible at 16 miles; and there is a small fixed white light on the extreme edge of the beach, close to the actual channel, which sweeps close to the shore, with less deep water outside. About a mile off the Point of Ayre is Whitestone Bank, marked by a gas-lighted boat and bell-buoy anchored in 4½ fathoms on the inner edge of the bank. The tideway on this bank is called locally the "Streuss."

The north channel flood tide flows very strongly south and east round the Point of Ayre. Its current is seen, even in calm weather, breaking in turbulent water sea wards where the soundings are not so deep.

On the west side of the island, the only lighthouses are at Peel, on the breakwater at the north end of St Patrick's Isle, and on the harbour pier-head. There is also a landmark tower, 675 feet above the sea, on the summit of Knockaloe Hill immediately overlooking Contrary Head: this tower is now an Admiralty observa tion station.

There are two main tidal streams in the Irish Sea, viz. that through the St George's Channel, from the south; and that through the north channel, from the north west. The south stream is parted at the Calf of Man to both sides of the island ; its easterly branch flowing past Langness, Douglas Head, and Maughold Head; the westerly branch flowing towards Contrary Head. The north-west stream from the west of Scotland meets the south stream off Contrary Head, and its other branch flows past the Point of Ayre to meet the south stream on the Bahama Bank. With the ebb these currents set in the reverse directions.

The coast-line of the Isle of Man from a point five miles north-east of Peel extending round the Point of Ayre to Ramsey is without indentation. The margin of this land ends in steep scarps of sand, gravel, and clay, with a fine sandy shore along the foot of the cliff. Along this coast the sea is slowly advancing on the land, except at the Point of Ayre, where the low spit of the Ayre is extending itself seawards.

The reach of coast where erosion is most active is that of the parishes of Kirk Michael, Ballaugh, and Jurby. This is open to the south-west and north-west winds, and from these quarters blow the heaviest gales. Whenever a gale and spring tides occur together, the sea scours the cliff bank, and undermines and brings down slice after slice of the superincumbent gravel and sand. Every such storm marks an advance of the sea upon the land.

As this coast is all the way open to the attack of the sea, no protective work at any single point could defend any great length of the cliff. The cost of protective structures, on a scale sufficiently large to be effective, would be too great in proportion to the value of the land likely to be saved; and as the process of destruction is very gradual, such operations as have now and again been planned have never been undertaken.

It is probable that a range of dunes once lined the coast of Kirk Michael, Ballaugh, and Jurby in unbroken continuity, except where four streams in Kirk Michael, one in Ballaugh, one between Ballaugh and Jurby, and one between Jurby and Kirk Andreas, cut their way through to the sea.

A fragment of high dune survives in Kirk Michael; another, of more than a mile in length, around Orrys dale Head, which is partly in Kirk Michael and partly in Ballaugh ; while in Jurby this duneland still exists almost unbroken on the seaboard of that parish, the rounded hills of the dunes being in several instances crowned with burial cairns, locally called "cronks." Along the coast of Kirk Andreas the dunes are continuous, and gradually recede from the coast, crossing the parish of Kirk Bride to end in a sectional scarp on the shore of Ramsey Bay.

Ramsey Bay is no doubt the work of sea erosion. The destruction of the coast is still perceptibly going on, though in a less degree than along the Kirk Michael shore. Within historical times the sea-front of Ramsey extended much further into the bay. Ramsey in part stands on the Mooragh, which is a fragment of what was once Ramessey Isle, the rest of the islet having gradually been destroyed by the sea. In 1511 Ramessey Isle was a farm on the delta between two estuaries of the Sulby river. The two estuaries have been filled up, and a new channel for the river cut direct through the Mooragh the Mooragh now forming the sea-front promenade of the town, with strong sea-walls to ward off any further incursions of the sea.

For a mile east from Ramsey, towards Maughold Head, the margin of the land under the hills consists of steep cliffs of boulder clay, which are rapidly under going erosion. Even in quite recent times the coast line has retreated considerably; an ancient fort on the sea brows at the mouth of Ballure Glen having all but disappeared within living memory. In the other direction from Ramsey, along the perspective of the bay shore towards the Point of Ayre, the sandy cliffs are gradually but steadily being swept away by the scour of the tides.

Peel, looking West from Cregmallin

In the bays of Douglas, Peel, Castletown, and Port St Mary the same force of destruction, or it may be said of formation, has been at work. At Douglas and Peel sea-walls now surround the crescents of the bays; but at Peel the sea has made breaches in the wall over and over again, involving a considerable cost on each occasion.

At Castletown, especially under Hango Hill, the sea has made great advances on the land within historical times: further advance however is checked by a sea wall, the part under Hango being rendered necessary in order to prevent a total destruction of the historic mound on the edge of the cliff.

Around Port St Mary Bay the sea's advance has been stopped only after the clays and gravels have all but dis appeared, and the denuded ledges of rock have become a barrier somewhat higher than the levels of the highest tides. Where the coast is rocky there is of course no perceptible erosion of the hard rocks of the island.

At the Point of Ayre the land is advancing further into the sea, because here the tidal eddies are evidently heaping up material abraded from other parts of the coast.

The climate of a country or district is, briefly, the average weather of that country or district, and it depends upon various factors, all mutually interacting-upon the latitude, the temperature, the direction and strength of the winds, the rainfall, the character of the soil, and the proximity of the district to the sea.

The differences in the climates of the world depend mainly upon latitude, but a scarcely less important factor is proximity to the sea. Along any great climatic zone there will be found variations in proportion to this proximity, the extremes being "continental" climates in the centres of continents far from the oceans, and "insular" climates in small tracts surrounded by sea. Continental climates show great differences in seasonal temperatures, the winters tending to be unusually cold and the summers unusually warm, while the climate of insular tracts is characterised by equableness and also by greater dampness. Great Britain possesses, by reason of its position, a temperate insular climate, but its average annual temperature is much higher than could be expected from its latitude. The prevalent south-westerly winds cause a movement of the surface-waters of the Atlantic towards our shores, and this warm-water current, which we know as the Gulf Stream, is the chief cause of the mildness of our winters.

Most of our weather comes to us from the Atlantic. It would be impossible here within the limits of a short chapter to discuss fully the causes which affect or control weather changes. It must suffice to say that the conditions are in the main either cyclonic or anticyclonic, which terms may be best explained, perhaps, by comparing the air currents to a stream of water. In a stream a chain of eddies may often be seen fringing the more steadily moving central water. Regarding the general north easterly moving air from the Atlantic as such a stream, a chain of eddies may be developed in a belt parallel with its general direction. This belt of eddies, or cyclones as they are termed, tends to shift its position, sometimes passing over our islands, sometimes to the north or south of them, and it is to this shifting that most of our weather changes are due. Cyclonic conditions are associated with a greater or less amount of atmospheric disturbance ; anticyclonic with calms.

The prevalent Atlantic winds largely affect our islands in another way, namely in their rainfall. The air, heavily laden with moisture from its passage over the ocean, meets with elevated land-tracts directly it reaches our shores-the moorland of Devon and Cornwall, the Welsh mountains, or the fells of Cumberland and Westmorland -and blowing up the rising land-surface, becomes cooled and parts with this moisture as rain. To how great an extent this occurs is best seen by reference to the accom panying map of the annual rainfall of England, where it will at once be noticed that the heaviest fall is in the west, and that it decreases with remarkable regularity until the least fall is reached on our eastern shores. Thus in 1906, the maximum rainfall for the year occurred at Glaslyn in the Snowdon district, where 205 inches of rain fell ; and the lowest was at Boyton in Suffolk, with a record of just under 20 inches. These western highlands, therefore, may not inaptly be compared to an umbrella, sheltering the country further eastward from the rain.

England & Wales Annual Rainfall

The above causes, then, are those mainly concerned in influencing the weather, but there are other and more local factors which often affect greatly the climate of a place, such, for example, as configuration, position, and soil. The shelter of a range of hills, a southern aspect, a sandy soil, will thus produce conditions which may differ greatly from those of a place-perhaps at no great distance-situated on a wind-swept northern slope with a cold clay soil.

As in England the climate of one district differs considerably from that of another, so even in a country of such small area as the Isle of Man there are considerable local differences.

Generally it may be said that the climate of the island is remarkably equable; much more equable,-i.e. with less difference between summer and winter-than the climate of the Isle of Wight. The Isle of Wight, in latitude 50°' 40' N., has a mean annual temperature of 50° Fahr. ; the Isle of Man, in latitude 54° 12' N., a mean annual temperature of 49°. That is to say, the Isle of Man is less warm, but is more equable, or with less difference between summer and winter; the actual variation being for the Isle of Wight 24°, and for the Isle of Man 17°.

Generally the mean annual temperature of the Isle of Man is lower than that of the seaboard of the English Channel, but very slightly higher than that of the sea board of Norfolk and Suffolk. It is an interesting fact that the mean temperature of the Isle of Man is practically the same as that of England taken as a whole.

These conditions of climate are the effect of the island being surrounded by the Irish Sea, and of the sea-water temperature of the Irish Sea being influenced by the Gulf Stream entering it by two separate channels, viz. (1) by the St George's Channel from the south, and (2) the North Channel from the north-west.

The rainfall on the island varies considerably, in different localities. It is least at the Calf of Man, with an annual average of 25·7 inches; and at the Point of Ayre, with an annual average of 28'1 inches. But at Douglas the annual rainfall is 44·5 inches; at the Dhoon on the east of Snaefell 60·3 inches; at Druidale on the moors on the west of Snaefell 61·8 inches. The average for the whole island is 46-4 inches-compared with 32 inches for the whole of England.

But what makes the climate of the island less pleasant than might be inferred from the recorded temperature and rainfall is the almost incessant winds, especially from the south-west : the winds being more felt by reason of the absence of timber. The total area of woodland on the island is just 1000 acres, the greatest part of it being in Lezayre, in the valley near Douglas, and on some glen sides and hill slopes; consequently the whole country is bare, and exposed to the full sweep of breeze and gale. The air is exceedingly pure and healthful, but with a certain bleakness consequent on the bareness of the land scape. The changes of the barometer may be said to be anticipated by the changes of the sky and the breeze : and the first impression-and the last impression-of ever so short a stay on the island is the changeableness of the Manx climate.

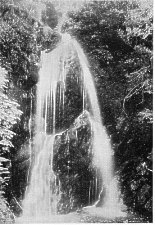

Dhoon Falls

In certain favoured low-lying localities, such as Crosby and the Union Mills, in the central valley, with a southern aspect and the shelter of the lesser hills, the conditions are most agreeably mild and restorative to invalids; but at no spot on the island is it possible to be more than six miles from the sea coast, and even the interior glens are affected by the equalising influence of the sea.

In the West Highlands of Scotland, the English Lake District, and the Welsh mountains, the annual rainfall is always over 80 inches annually; and in Cumberland local falls of 174 and 185 inches have been registered. Compared with these districts the island has a small average of rainfall. An accurate record kept in the neighbourhood of Douglas gives the number of days on which rain fell, averaged for ten years, as 196. Thunder storms are very uncommon : they average nine per year, and none of them are violent.

The mean aggregate of hours of bright sunshine shows that the Isle of Man, though its climate is humid, is also sunny. It stands third in the list of the 12 districts into which Great Britain and Ireland have been divided, with 1589 hours of bright sunshine. The Channel Islands have 19o9 hours; S.W. England, 1628 hours: all other districts having a less duration of sunshine than the Isle of Man, from 1572 hours in the South of England to 1253 in the North of Ireland and 1196 in the North of Scotland.

Contrasted with the opposite coast of Lancashire, fogs are less frequent and less dense on the Manx coast. The prevailing winds are south-westerly, north-westerly, and easterly ; the latter, occurring in the spring, are less keenly felt than on the English side of the channel.

|

|

||

|

Any comments, errors or omissions gratefully received The Editor |

||