[From Manks Antiquities, 1914]

The Historic Period is represented by structural and monumental remains dating from the introduction of Christianity to the earlier Celtic inhabitants, probably in the fifth century. Among these remains are a number of inscribed stones and incised and carved Cross-slabs (see figs 37 to 51) ; and the ruins and foundations of early Keeills, Cells, or Churches.

In our first Edition we quoted from Dr. Oliver writing in 1868 (Manx Society, Vol. XV.), on the subject of the Keeills or early Churches, but added that we were " unable to follow his classification or to agree with his description in every particular." We then gave examples of some which had been partially examined. Since that time the Archaeological Survey of the Island has been undertaken by a Committee of the Isle of Man Natural History and Antiquarian Society ; and three fully-illustrated Reports have been published dealing with the Keeills in the three Northern Sheadings, while the survey is practically finished of a fourth Sheading, viz., that of Garff. A good deal has been brought to light by the careful and methodical excavation and examination of all the ruins of Keeills now remaining, and something has been learned from local sources both of these and of many more which are entirely destroyed.

If, as is not unlikely, the very earliest Churches in the Isle of Man were as elsewhere built of sods or of wattle and mud, there are now no remains of such ; but, in one or two instances burial places have been found with lintel-graves of the Christian period yet with neither trace nor tradition of a building, and this may possibly be due to the fact that such buildings were of mud and not replaced by stone. The survey has found, in the half of the Island examined, the remains or sites of 62 Keeills, while in Garff they account for 30 more; of these however not more than 23, and 8 in Garff, have now even the foundations left. They date from different periods, from possibly the close of the seventh to the fourteenth century. The plans show different proportions bringing the buildings into three distinct groups which correspond generally with a difference in size. Thus a good number, including the most primitive mode of building, have the length only about one- third more than the breadth, e.g., Lag-ny-Keeillee, at the foot of Cronk-ny-Irree-Laa, in Patrick, measures only 13 ft. long by 8 ft. 6 in. wide. Others have the length twice the breadth as in St. Patrick's Chapel, Peel, which is 22 ft. 4 in. long by 11 ft. 8 in. wide. A few more, still larger in size and distinctly later in the style of building, show the length about three times the breadth, and these are the proportions which were followed in the old parish churches. A good example of this group is to be seen in St. Patrick's Church, Peel, which has a length of 57 ft. and a breadth of 18 ft.

There are, too, three different modes of building, each showing a marked advance on the other. The most primitive of these seems to be that still frequently followed in building field fences; there is an outer and an inner facing of stones built in irregular courses, the interstices filled with earth, the space between the facings being packed with soil and rubble. A second kind, in which the buildings are of larger size, has the walls of stone with clay for cement. The third shows the modern style of building with lime, sometimes shell-mortar, though even in these the stones are mere undressed slabs or boulders, weathered and evidently picked up from the surface or brought from the sea-shore.

The distinctive character in the plan has continued from the very earliest of these remains until quite recent tunes, and may still be seen in most of the parish churches. This plan is invariably rectangular, there is no apse or rounded end, but the east gable like the west is at right angles to the side walls. Even more remarkable is the fact that there is no architectural division between the Nave and the Chancel ; in only three comparatively late instances is there any trace of a division in the form of foundations of a wall, not bonded into the side walls, which may simply have formed a step upon which there may have been a rail or rood-screen of wood, namely, St. Trinian's, Marown, the Chapel of St. Michael's Isle, and, as recorded by Cumming, St. Patrick's Church, Peel.

The Manks word " Keeill," whether derived from the Latin Cella, or, as has been supposed, from an older Celtic word meaning a grave, is the same as the Irish and Gaelic Cill or Kil, met with as a compound in so very many place- names, as Kil-dare, Kil-marnock, and in the Isle of Man is associated only with the little Churches of the Celtic period, later buildings being spoken of simply as Church or Chapel, e.g., the Church and the Chapel of St. Patrick, Peel, the Chapel on St. Michael's Isle, St. Trinian's Church, and so on. The word " Cabbal," an evident corruption of the English " Chapel," is sometimes used for an ancient building, but is probably recent and applied after the older native word had been forgotten. When the Norse rulers, so closely connected with the reigning house in Dublin, became Christian, they naturally introduced the Anglo-Catholic system with which they were acquainted in Ireland. There is in the Island no evidence of hostility between the two, but the Celtic, as else- where and for the same causes, gradually faded away. The Scandinavian " Kirk " superseded the Celtic " Keeill," and is still applied to all the Parish Churches, that ecclesiastical division having originated under the Norse Kings of Man.

The Keeills would in the first instance have been erected as Oratories or little Chapels in which the first Christian missionaries could offer up their simple service of prayer and praise. Obviously they were not intended for congregational worship ; preaching would be conducted out of doors ; baptism also would be outside, perhaps at the well which is often found near by one of these Keeills. A few stone fonts have been met with, but when they first came into use is at present unknown. The doorways would seem too narrow and too low for funerals, and the service was probably conducted at the grave-side, yet a number of burials have been found within the Keeills themselves.

As regards structure, the walls of these buildings from first to last were of weathered slabs picked up from the surrounding surface, and, in the north of the Island, of shore boulders. Oswald gives an account of one on Ballakilley, Malew, with a gable, now destroyed, of which we reproduce his figure (fig. 32). The district abounds in ice-borne boulders of Foxdale granite scattered over the surface, which accounts

Fig. 32.-Keeill at Ballakilley in 1867.

for the material used in the building. It measured 21 ft. by 9 ft. " The western gable crowned with ivy is still standing, but the east end is in ruins. It is built of rounded boulders of granite and quartz giving it a very peculiar appearance. The walls are 6 ft. 3 in. from the ground to the spring of the roof ; and the western gable 16 ft. 9 in. to the peak. In the south wall near the eastern angle is the door of entrance 5 ft. 2 in. in height by 2 ft. 6 in. at base, diminishing upwards to 2 ft. Opposite in the north wall is a square-headed window, and another in the south wall near the west end" (see fig. 32). The floors of these Keeills were paved, but sometimes with stones so rough and so irregular in size and shape as not easily to be distinguished ; generally there was a slight but steady rise from the west to the east end. The roofs would be thatched with rushes, bent, or ling, according to the locality. In one on Ballahimmon, between Rhenas and Little London, there were found loose two " Bwhid suggane," that is to say, stone pegs set in the walls for fastening the thatch. Only eighteen of those examined had remains of doorways, of these fourteen were in the west gable, one in the south wall near the west corner, and one, Ballingan, Marown, in the south wall at its east end ; one was in the north wall near the west angle ; another in the north is that of St. Patrick's Church, Peel, which may date from about the beginning of the eleventh century. Omitting the group of larger and later buildings, the average width of doorways examined was only about 21 in. Not one was so perfect as to show its height, but that of Ballakilley recorded by Oswald as 5 ft. 2 in. may perhaps have been the average. The sides of the doorway were built in courses, but frequently faced by large stones set on end ; there was generally a sill outside and inside formed by a flag on edge and almost always a step down to the floor inside. Four socket- stones have been met with, one at Lag-ny-Keeillee being in position within the doorway on the south side. The width was so slight as to have been easily filled by a stout wooden door of a single plank, which would be furnished with an iron heel to fit into this socket and with a pin to fit into the lintel. At Lag-ny-Keeillee we found loose just outside the building a large flag, 57 in. by 25 in. and about 5 in. thick ; this had a hole countersunk in its side, and it was found that this would have been exactly over the socket if set as a lintel so as to have 18 in. of its length in either side wall and to project inwards for 3 in. At Ballingan and at Greeba Mills were broken slabs each with a similar hole in the side which apparently had served as door lintels, showing the doors to have been flat-topped.

Remains of windows were even more rare than of door- ways ; none were perfect except at St. Patrick's Chapel, Peel, which has a square-beaded window in the east end ; but in one case-Lag-ny-Keeil-ee-there had been a carved window- head cut out of a fairly flat, sub-triangular boulder of Silurian sandstone, which showed that the light had been flat-topped, with an opening of 6 in., expanding downwards ; above this opening is a very simple, curved, bead-moulding less than half an inch in relief. The windows mentioned by Oswald

Fig. 33.-Plan of Keeill at Ballaquinney, Marown. [more detailed from ref]

were square-headed, and their height 2 ft. 6 in., which seems a likely average; they generally had an internal splay with a width inside of about 18 in., needless to say they were not glazed, their narrow opening and outward falling sills being sufficient to keep out the beat of the storm ; where the sill- stones remained they were only from 2 ft. to 3 ft. 6 in. above the level of the floor-pavement.

In ten cases some remains of an altar were found on excavation, always set against but not built into the east gable. The average size of seven of these was 3 ft. 8 in. by 2 ft. 1'- in. ; in one case only, at Knoc-y-doonee; Andreas, was it so far perfect as to have the top stone in position, fitting neatly to an upright slab which remained on the south side ; the height of this above the floor was only 2 ft., and in other cases the sills of the windows that remain show that the altar could never have been much higher. At Knoc-y-doonee, the core consisted of shore-boulders packed with sand ; in other instances slabs were laid lengthways-so that each course crossed the one below at right angles, the interstices filled in with soil ; some were of earth with a number of small flat stones set without any particular arrangement ; in such an altar, at Ballaquinney, Marown, there were found the broken fragments of two early cross-slabs at about the level of the floor, and, as we cannot suppose they would have been so used until the memory of those to whom they had been erected was forgotten, this shows that the altar, if not also the Keeill, had been a re-erection, and later than the early seventh century. The altar would seem always to have been faced with slabs of unhewn stones ; sometimes the front was covered by a single large flag on edge, as at Cronkbreck, near St. John's, where, bowever, stones must have been built in courses above the slab which stands only 9 in. high ; in others there were three or four slabs of different height set on end, as at Keeill Pheric-a-dromma, German. At Cabbal Druiaght, Marown, and in one or two other instances were found small upright pillars at the fore-corners. No trace of a " reliquary " was found either in or under any of these altars, but, in two instances, there was a carefully-built recess in the east wall immediately behind the altar, about 18 in. deep, 16 in. high, and 12 in. wide, which might have been intended for a safe place of concealment for the sacred vessels at a time when they were liable to the pagan raids of the Norse Vikings. In a Keeill at Maughold, a similar recess appears in the middle of the north wall.

Fig. 34.-Plan of Cabbal Druiaght, Marown. [from ref]

We know that at the introduction of Christianity into other Celtic lands, when a grant of land was obtained from the chieftain--if indeed he did not present them with a Fort-it was customary for the missionary to erect a " Lis " or " Caisel," within which to place his Church as well as the dwellings of those who became Christians, and that this custom was long continued. Possibly this may be the explanation of some of the larger enclosures found in connection with a few of the early Keeills, as at Rhaby, Patrick; Ballaquinney, Marown ; and Balladcole, Arbory.

Relics of a later state of things have come to light. From about the end of the seventh century, the monastic system had developed a class of clerics known as Culdees ; when the system was breaking up, lands and Churches having fallen into the hands of laymen, the duties were often performed by these Culdees. At Lag-ny-Keeillee, where the original boundaries of the cemetery are almost perfect, and there is also on its northern side a separate enclosure, drained, fenced and levelled evidently for cultivation, there was found outside the corner, formed by the two enclosures, the foundations of a cell which measured inside about 9 ft. by 6 ft. The style of building resembled that of the Keeill ; there had been a paved floor, a door looking northwards, and a window in the south wall. It was, no doubt, the dwelling of the Culdee who served the Keeill. At Cabbal Pheric, the Spooyt Vane, Michael, a similar cell was found outside the S.W. corner of the cemetery.

Fig. 35,-Plan of Lag-ny-Keeillee.

A, the Keeill surrounded by the burial ground;

B, the Culdee's cell;

C, pile of loose stones.

So far there is nothing to show when slate or stone was first used for roofing ; that the early buildings were thatched is shown by the discovery of the stone pegs used for the purpose, as well as indicated possibly by distinct traces of burning which have been met with. The socket-stones and pierced lintels show that they sometimes had wooden doors, and in those in which the continuous pavement shows no place for a socket-stone, the narrow doors, like those of the dwellings of the period, were probably protected by a bundle of saplings, or a gorse bush. Two instances are known, Ballacarnane, Michael, and Ballakilpheric, Rushen, where large stone pillars were set in front of the doors. Later buildings, as at Maughold and on Peel Isle, show projecting walls, probably of roofed porches.

Cresset-stones, met with in a few instances, and stone lamps found in Kirk Bride, may have been used for burning on the small altars, and the mode of kindling is shown by a fine, polished, flint strike-a-light, found in the Ballaquinney Keeill, Marown.

A remarkable thing is that many Keeills proved to have been erected on older heathen burial sites which, so far, appear all to have been of Bronze Age-not only worked flints and charcoal and burnt bones being found, but fragments of pottery of that period. In every case white shore pebbles were met with, sometimes in great numbers, and some previously undisturbed graves showed that sometimes, at all events, these had been used. to cover them; in one case eighty were counted forming a covering to the grave over which the soil was then heaped.

It is in connection with these old Keeills and the later Parish Churches, some of which are on ancient sites, that the carved stone monuments have been found in which the Isle of Man is so peculiarly rich. With but few exceptions these are sepulchral, and take the form of upright slabs of local stone, ranging from about 2 ft. 6 in. to 6 and, in a few cases, 7 or 8 ft. high, by about 15 in. to 24 in. wide, and from 2 to 4 in. thick. They are generally " rectangular, sometimes having the upper corners rounded off, and sometimes the whole head in what has been called a wheel-cross. Occasionally the spaces between the limbs and the surrounding circle are pierced, and, in a very few instances, the slab is itself cruci- form."1

Fig. 36. Ogam Inscribed Stones. 1, 2, Ballaqueeney ; 3, Bemaken Friary.

Of the inscriptions, a few are in " Ogams "-characters forming an artificial alphabet, invented possibly by Irish scholars, who had become acquainted with the Roman inscrip- tions in Wales. Two of these have been found at Bemaken Friary, Arbory, and two in the burial ground of an early Keeill at Ballaqueeney, Port St. Mary, Rushen. In language and character they exactly resemble Irish inscriptions of about the fifth century (see fig. 36).

At Maughold, the Ogam alphabet has been cut beneath a runic inscription on a stone of the thirteenth century, and, at Michael, two on the twelfth century Harper Cross belong to the class of " Scholastic " or " Pictish " Ogams met with in Scotland and the Isles. The latest discovery made in the course of the Archaeological Survey in 1911, was that of a bi-linnual inscription at Knoc-y-doonee, Andreas. A stone pillar about 6 ft. high by 17 in. wide and 7 to 8 in. thick was found to have on one face an inscription in Roman capitals- AMMECAT FILIVS ROCAT HIC IACIT ; whilst up the left side are remains of the same in Ogams-[AM]B[E]CATOS MAQI ROCATOS. This may date from the middle of the sixth century.*

Fig. 37. Early forms of Linear Crosses.

Fig. 38. Early forms of Crosses in Outline.

One or two inscriptions are in debased Roman, or Early British characters and

Latin language of the sixth, seventh, or eighth centuries. The most interesting

of these is a small slab found at Maughold,* and figured and described in "

The Reliquary and Illustrated Archaeologist," July, 1902. Around a circle enclosing

a Hexafoil design is the following inscription in mixed capital and small letters,

of which, unfortunately, the beginning is broken off :-. . . NE ITSPLI EPPS

DE INSVL. It is here met by some characters running in the opposite direction,

of which one can make out the letters-BPAT. Below the circle are two small crosses

(of the very rare form met with at Kirk Madrine, Wigtown) down by the sides

of which runs the following unique formula :--

[FECI] IN Xpi HOMIHE

CRVCIS Xpi IMAGEHEM.

With two exceptions the H form stands for N (fig. 39).

Fig. 39.-Inscribed stone from Maughold,

This is probably earlier than the eight century. Another cross, formerly on a hedge at Port-y-Vullen, Maughold, whence it had been removed about 1850 from the adjoining field, in which there is known to have been a burial ground, with doubtless a Keeill in connection with it, bears across the edge the simple inscription, Crux Guriat, a name met with in North Wales in the ninth century. The upper part of our figure 40 shows the inscription from a rubbing, one-fourth actual size. The greater number of these inscriptions are, however, in " Runes," the peculiar characters developed three or four centuries before the Christian era by the Goths, who came in contact with the Greek colonists from the Black Sea trading for amber. These characters underwent great changes in the course of centuries, and are classed according to their period as Gothic, Anglian and Scandinavian. Two examples of the Anglian runes of about the eighth century have been found at Maughold. The characters are perfectly legible, reading in the first-BLAGC-MON. This would make a known Anglo- Saxon name.

Fig. 40.-Inscribed Cross from Kirk Maughold. Crux Guriat.

In 1906 the fragment of another was found at the same place which gives what appears to be the termination of the same name-[BLAK]GMON. Both of these show the early form of cross patee within a circle as on the fragment, also from Maughold, with remains of the symbol Alpha and Omega, and the three are probably work of the seventh century. The rest of the Manks inscriptions are in the later Scandinavian runes of the tenth to the thirteenth centuries.

Fig. 41.-Runic Inscription from Corna in Maughold.

One of the latest is a very interesting inscription, not sepulchral, on a rough, unhewn, slate slab (fig. 41) cut apparently with the point of a knife. The formula, with an invocation to Christ and the three great Irish Saints, differs from any previously met with, namely :-

" Krist : Malaki and Patrick: (and) Adamnan

" But of all the sheep Juan is the priest in Kurna dal."

The runes in the last word " Kurna " express the present day pronunciation of the glen or "dale" where stands the Keeill by which this stone was found.

The language and character of the runes prove this to have been cut about the beginning of the thirteenth century. The same priest Iuan, probably a few years later, carved both runes and ogams on another somewhat similar rough slab at the Parish Church, where both may now be seen.

The earlier pieces bear on one or both faces incised crosses of different forms without decoration and very rarely inscribed. Some of these are shown in our figs. 37, 38.

Only three of these early pieces are cruciform in outline, two at Andreas, and one each at Bride and Maughold. Several examples show a purely linear cross incised on the slab and of the most simple form possible; sometimes contained within a ring either circular or oval. A development shows two or more of the limbs crossed near the extremity ; one of these, at Conchan, more elaborate, has the upper and lower crosslet within a small circular ring, the whole contained in an oval. At Jurby, a slab shows these cross-lines set at an angle to give the impression of expanding ends to the limbs, and one at Marown has the cross-lines curved, suggesting the favourite D-shaped termination to the limbs met with in Ireland at a later date.

An advance on the linear form is to have the cross cut in outline, in which we find the plain Latin and the equal-limbed cross with or without surrounding circle or oval, and sometimes having circlets between the limbs. Then we have a form with expanding limbs, but still set at angles, for example at Peel, where two show the upper and lower limbs widely expanding, one of them resembling the Oriental Crux ansata. One from Patrick with expanding limbs bordered by straight lines leads up to the proper cross patee, formed by four arcs of circles conjoined or approaching at the centre ; it is a similar form at Maughold which shows the Alpha and Omega symbol (fig. 38). This brings us to the Celtic form of cross, that is to say, one having hollow, curved recesses at the junction of the limbs. Perhaps the earliest of these is a fragment at Maughold, but the most interesting is that recently discovered at Ballavarkish, Kirk Bride, which bears inscriptions in Latin, showing its date to be about the seventh century.

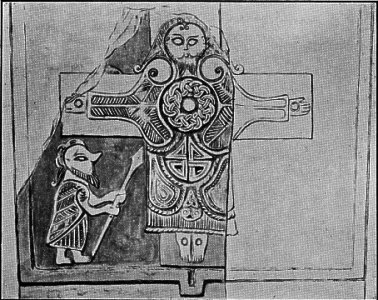

Fig. 42.-Crosses at Conchan, restored.

Later, we find the cross sculptured in relief upon the face of the stone, having more or less elaborate decoration on its surface or on the spaces at either side of it ; and it is interesting to trace the development of their art characteristics from the simple plait and twist to most complex and beautiful geometric designs, such as are to be met with generally in Hiberno- Anglian art of the period. This is succeeded by zoomorphic work and by well-drawn figures of beasts, birds and human beings, though certainly in some of the earlier pieces the figure- drawing is rather feeble. A very few of the older Celtic pieces bear Scripture scenes. Daniel in the Lions' den, on a fine wheel-headed stone at Kirk Braddan, can only be recognised by a comparison with a series of early monuments dealing with that subject. The Temptation of Adam and Eve at Kirk Bride is not upon a cross, but appears rather to have been an architectural detail in the twelfth-century Church there ; it has some peculiarities, the most striking being the total absence of a serpent. The Virgin and Child on the large slab at Kirk Maughold (fig. 45) must be one of the earliest instances of the treatment of that subject on stone, and is unique with respect to the position of the Child which is held not across the bosom of the Mother but at her side, her hand clasping it round the back. The Crucifixion from the Calf of Man (fig. 43) is remarkable both for its rich decorative treatment and for the delicacy of its workmanship, being more like an engraving than a piece of sculpture; it must date from the eighth or beginning of the ninth century, and seems to have been designed by an artist who derived his inspiration directly from Oriental sources.

Fig. 43.-Cross from Calf of Man.

Very interesting it is to note the work of the first Scandinavian Christian sculptors, following the earlier Celtic models with great freedom and evolving effective designs from the most simple motives. Anglian influence is clearly traceable in these as it is in some of the Celtic pieces, but the actual designs are in many cases peculiar to the Isle of Man. Finally, on many of the later Scandinavian monuments we meet with illustrations from the old Norse myths as handed down in the Sagas, some not elsewhere depicted, and all showing artistic freedom and originality of treatment. Among these we have a series with scenes from the popular story of Sigurd Fafnisbane and another series with representations of the high gods, Odin, Thor and Heimdall, together with figures of wise-women, of giants, dwarfs and monsters.* A complete collection of casts of over a hundred cross-slabs, taken for P. M. C. Kermode by Mr. T. H. Royston, of Douglas, now finds a temporary location in Castle Rushen ; to this additions are being constantly made by the Manx Museum Trustees as further pieces are brought to light. The originals have now been collected by the Trustees, and, excepting the four precious Ogam stories which are in the Museum, have been set up in special shelters accessible to all, at the Churches of the parishes to which they respectively belong. A hundred and seventeen of these are figured in " Manx Crosses," published in 1907 by Bemrose & Sons, and twenty, which have since been found, are described and figured by the author of that work in the Proceedings of the Society of Antiquaries of Scotland (Vols. XLV.-XLVII.). We here reproduce some typical examples.

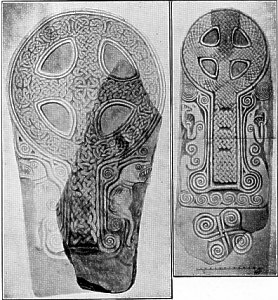

Fig. 44. Celtic slab, Kirk Maughold.

Fig. 44. A fine instance of Celtic design and workmanship from Kirk Maughold, that district in which about a third of all those found throughout the Island have been discovered. The cross has a plain border terminating at the foot of the shaft in volutes, and is decorated with a simple form of plait, the limbs being connected by a bordered circle. The stone is unfortunately broken along its length ; the remaining space by the side of the shaft shows the robed figure of a priest ; below the cross are stags and hounds, the former having the antlers represented in a conventional fan-shaped manner, which, as well as the angular jaws of the beasts, differ from any other example. Below the stags is the hunter in flowing robes riding forth to the chase. The other face bears a cross of more ornamental design, its shaft decorated by a loop-twist of two cords which is carried in a smaller single-cord loop-twist round the circle, the limbs of the cross having a separate design of plait-work. There is an effective use of volutes and spirals, and the space by the side shows a boar-hunt with the broken figure of a stag pursued by a hound.

Fig 45.-Cross-slab showing Celtic art with, possibly, Anglian influence.

Fig. 45. This large slab, also at Maughold, in our former edition was assigned to " Roolwer," a Scandinavian recorded in Chrouicon Mannie as Bishop in Man and as buried at Maughold Church about 1060. In a review of " Manx Crosses," Mr. Collingwood, who has made a special study of such monuments in the north of England, thinks it might be a hundred years older than that date, and of Anglian origin. The designs though characteristic of the period are not distinctively Anglian, but the shape of the cross on each face as well as the decorative treatment generally differs from any other in the Island. The large cross occupying the whole carved surface of one face has in the recesses between the limbs the only Manks example of the favourite Celtic triple spiral, while the angular key-fret so freely used occurs otherwise only on the much later Thor Cross at Kirk Bride. On the upper limb of the cross is the figure of a man, who, from the pastoral staff at his side, is evidently intended to represent either a Bishop or an Abbot; the lower limb shows the Virgin and Child referred to above, p. 100, with an unusual form of nimbus which may have terminated in fringes. In the centre is a ring decorated with step-pattern, at either side of which is a bird. This was rather a favourite early Christian symbol. In our later Scandinavian pieces the design of the two birds is not infrequent, but they are set above instead of on the limbs of the cross. The lower half of the other face is occupied by a rectangular panel, broken above and below by a step, and divided up the middle by a band ; on one side is shown a robed rider on horseback, on the other, two antlered stags followed by a hind pursued by a hound, at the back of which is some rude scroll-work. Between the panels are double volutes and angular key-fret. One of the edges bears a unique design of incised curves with dots, giving a suggestion of a twist, below which are key and plait devices. The other edge, also incised, has a good angular key design above, with interlaced diagonal loops, volutes and plait-work below.

Our Sigurd pieces are here represented by three broken slabs, one each from Jurby, Malew and Maughold. A very interesting one may be seen at Andreas, and, recently, another fragment showing the steed has been found at Michael. Nowhere else have so many examples been met with, and it is evident that the Sigurd story was a special favourite among the Norse settlers in Man.

Fig. 46. The first of these, from Jurby, shows on the space remaining at one side, the dragon Fafni writhing in his death agony, and Sigurd piercing him with a sword. The Sagas relate that Sigurd was advised by Odin to dig pits and to conceal himself in one in order to strike the dragon as he passed over it. Owing to the cramped space at his command, the artist has ingeniously represented the pit by what looks like a hollow mound with an opening at the top. Below is another figure of Sigurd in the act of roasting the heart of the dragon, and having scalded his fingers with the boiling blood he cools them in his mouth-by which means he came to under- stand the language of birds. Below is the steed Grani and a peculiar conventional figure of a tree, at one side of which is one of the talking birds through whom Sigurd learned of the intended treachery of the dwarf Regin, who meant to devour the heart himself and so become the wisest and most powerful of beings, and then, having slain Sigurd, to carry off the treasure.

Fig. 47. The Malew slab shows on the brolien space at one side of the cross the steed, and, below, the remains of two panels unfortunately lost. At the other side Sigurd is seen holding the wand, upon which the dragon's heart is roasting, over a fire represented by three triangular flames, while he cools his burnt fingers in his mouth. The figure below shows again Sigurd from his pit piercing the dragon as he passes over. Both the figure drawing and the geometrical work are of a different type, and this is certainly later than the Jurby stone, and by a different artist.

Fig. 48. The Maughold slab is by yet another hand and of a still later date, and is suggested in " Manx Crosses " to have been a memorial to King Olaf the Red, who was slain at Ramsey in 1153. Upon this we see for the first time the beginning of the story, which tells how Loki, who was the mischief-maker among the high gods, found the Otter devouring a salmon on a rock by the Foss or waterfall, and stoned him to death. When it was discovered that the Otter was the son of Hreidmar, King of the Dwarf-kind, who assumed that form when he went a-fishing, Odin, Hoener and Loki, notwith- standing their godship, had to pay weregild ; for this purpose Loki then captured Andwari and robbed him of his treasure, including the celebrated ring which was to bring such a dreadful curse on all its future possessors. Further up on the panel is represented the later scene, when Sigurd, having slain the dragon, as well as Regin, who was brother to Fafni, seized the treasure and set it on the back of Grani to ride away and pass through the ring of flames to Brynhild the Valkyrie.

The many other pieces depicting scenes from the Edda lays are equally remarkable, and, being carved on Christian monuments and found so far away from their Norse home-land, are of the greatest possible interest.

Fig. 49.-Heimdall slab. Jurby.

Fig. 49. This is the head of an inscribed slab from Jurby, on which we may see Heimdall, the warder of the gods, standing at the foot of Bifrilst, the rainbow bridge, sounding the Gialla horn to summon the gods to their last great battle at Ragnarõk where they are to encounter the giants, demons, and all the powers of evil.

Fig. 50. The Thor Cross. Kirk Bride.

Fig. 50. The richest example anywhere known of such illustrations of the old Norse Mythology is the handsomelycarved cross-slab at Kirk Bride. Above the circle which surrounds the cross, and at either side of a rectangular panel, stands a small figure ; above the panel and connecting one of these figures with the other is a chevron design. By comparison with a hog-back monument of the period at Heysham,* we may recognise in the latter the Firmament which is upheld by four dwarfs here represented by the two small figures. Below the circle and by the side of another panel appears a man holding a staff-now too worn for one to say positively what it was intended for ; it might be Odin, father of the gods. Below this and separated from it by a panel of plait- work is a scene of trouble which seems to represent the trampling of victims under the hoofs of horses. Figures on the other side of the panel are more certain. The being attacking the serpent or dragon is undoubtedly intended for Thor, bearded and girt with his strength-belt, who at Ragnarõk is to slay the Midgarthsworm, and, stepping back nine paces, to be himself overcome by its deadly venom. Below is the mighty giant, Rungnir, who challenged Thor to mortal combat, and, when he thought the god was coming by the nether way and would attack him from beneath, cast his shield upon the ground and stood upon it. Thor slew the giant but fell under him, and, when none of the gods was able to raise him up, came his own son, Main, who, though only three nights old, had the strength to do so and was thereupon recognised by his father who presented him with the giant's steed as a gift. Main is here shown by the little figure running with out-stretched hand between Rungnir and Thor. The curious object at the other foot of Thor refers to another of his adventures when he carried off the giant's kettle to make a brew for Ægir's feast.

The other face of the stone refers to the adventure known as " Thor's fishing." He once visited the Giant Hymi intending to anticipate events by capturing and slaying Jormungand, the Midgarthsworm, one of Loki's evil brood. At dawn Hymi made ready his boat, and Thor asked what they should have for bait, but the giant who had no desire for his company replied that he might go look for bait for himself. Looking around he saw Hymi's oxen grazing on the hillside and seizing the largest of these, wrung off his head and hurried back to the strand as the giant was pushing off in his skiff. On this stone the great plaited beard and the strength-belt mark the god, and, to emphasise the fact that he is intended and no other, the sculptor has made the upper end of the border of the panel to terminate in the form of a dragon's head like that shown on the other face. Below this, the lowest panel figures the two dread hounds of the Eclipse, Garm and that other who, at Raguar6k, are to swallow the sun and the moon.

Fig. 51.-Odin Gross. Kirk Andreas.

Fig. 51. Our last example shows on a small broken stone from Andreas the figure of a man, bare-headed, armed with a spear which he plunges into the breast of a wolf. The Raven at his shoulder indicates All-father Odin, to whom he is whispering that this is the end of all things, that Odin shall be swallowed by the Fenris wolf, most dreaded of all the monsters, but-" straightway Vidar shall dash forward and rend the Wolf's jaws asunder and that shall be his death . . . Thereupon Swart shall cast fire over the earth and burn the whole world: and every living thing shall suffer death . . . and the Powers shall perish."

The other face of the stone proclaims the new order of things-" There shall come one yet mightier, though Him I dare not name." We behold the figure of a Man, belted, his face turned to the cross ; in his left hand he holds up a cross, in his right the Book. Serpents are writhing below and around. The fish in front of him is the well-known Christian symbol founded on the Greek acrostic ; the knotted serpents witness the triumph of Christ over the Devil, the treading on the adders, or bruising the serpent's head.

* Catalogue of Manks Crosses, P. M. C. Kermode, 2nd Ed., p. 4.

* Note on the Ogam and Latin Inscriptions from the Isle of Man, and a recently found bi-lingual in Celtic and Latin. By P. M. C. Kermode, Proc. S.A.Scot., Vol. XLV., p. 449.

* By P. M C. Kermode, in 1901.

* For the Sigurd story readers should turn to " Volsunga saga : The Story of the Volsungs and Niblungs," by Erikr Magnüsson and William Morris. (The Walter Scott Publishing Co., Ltd.). For the Norse Mythology, a popularly written handbook is " The Heroes of Asgard," by A. and E. Scary. (Macmillan & Co., 1908.)

* Trans. of the Lancashire and Cheshire Antiquarian Soc., Vol. V., pl. 6 ; and Vol. IX., pls. 9, 10, 11.

|

|

||

|

|

||

|

|

||

|

Any comments, errors or omissions gratefully received

The Editor |

||