Douglas - Harris Promenade in Olden Days.

[From The Manxman, #2 1911]

By ONE OF OUR OLDEST M.P.'s,

"When my informant found out who I was, I really believe she would have kissed me. "

In sending you another batch of my Manx reminiscences you, Mr. Editor, were so good as to wish me to do let me before proceeding to express my gratification that you were able to reproduce pictorially the scene of what I may call, and doubtless what your readers will consider. the principal and most interesting incident in my former collection — the old school- house. to wit. in which I began my education proper alongside of the boy who turned out "the most famous Manxman who ever lived," and a portion of the field hard by, whereon that most famous of Manmxmen proved his valour in face of another boy from the adjacent island of Great Britain, of whom all that can with confidence be said is that he is not (as yet, at least) the "most famous" of all that that island has produced, there being, at present. a few certainly ahead of him, as Bacon (alias "Shakespeare"). Milton, Wordsworth, "Tom Spring." and, perhaps, a few others. As the writer. however, of a monograph on the last (and, perhaps, greatest) of these great men— becoming. so to speak. the Homer of our great English Achilles — and as having, moreover, now associated his name in the immortal pages of the "Manxman." with that of the greatest of Tripodians (if he may coin an appropriate term), who knows where his final place may be on the poll of Immortals! Who knows that, when the fight in which he took part on that famous field behind the school-house is in the future referred to, it mmy not be described as the battle between the most famous Manxman and the most famous Englishman that ever lived"? Which thought, Mr. Editor, suggests innumerable possibilities. Why not, whilst that bit of field is still available for the purpose—why not, I say, erect thereon a statue to the greatest of all Manxmen. He might he represented im the act of shaking hands with his (in futuro) grest antagonist—a juncture symbolical of the union of hearts which has always existed between the two great little Islands.

And if this is not enough to do honour to the memory of your "most famous" man, why not, if possible, buy up that School House with the Class Room attached to it (seeing that, to my surprise, it still exists), and turn the premises in question into a memorial dwelling, after the examples of Burns's Cottage at Alloway, Dove Cottage at Grasmere, and the supposed birthplace of supposed Shakespeare at Stratford-on-Avon? I cannot but think that this would be "good business," as well as good taste, and then (who knows ?) perhaps beside or below the figure of the Great Manx Tom (who would, of course occupy the place of honour in such a museum) there might be found a place for a miniature of me — poor me, his humble English contemporary? But this is, of course, a matter of no consideration.

But I am wandering from my purpose, which was, not to dilate upon past recollections, but to relate new ones; but these are so linked up with those already recorded as to make separation somewhat difficult. For instance, speaking of that battle between the great Manxman and myself. brings to my mind another contest which took place almost on the same spot, and it was the first contest of the kind which I had ever witnessed in my life. For it was nothing less than a Cock Fight—yes, a real bona-fide Combat de Cogs à outrance — arranged and carried out secundum artem, With all the forms and ceremonies of the "game." And how I came to see it was this. Bursting out of school, as was our wont at midday. the attention of my schoolfellows and myself was attracted to the hats of a small crowd or company of men just over that wall which separated Imeson's premises from the (now) famous field. On to the top of that wall, boylike, we bounded, all curiosity to see "what was going on." There, beneath the crowd of hats, we saw the figures of the same number of men arranged in an irregular circle bounded by boxes or crates, and other accessories of the game in which our quick eyes could plainly discern the bright feathers and sparkling eyes of specimens of the gamest and stateliest of all feathered things. We also heard their crows of defiance — sharp and thrilling as the trumpet notes of the lists of the old days of chivalry, or the bugles of a more modern battle-field. In due course two of them were released from their several cribs and placed vis a vis on the Champ de Mars. Then followed manoeuvring : just as in a human conflict. Then the flash of lightning, of the gleaming spurs of steel, and then, sometimes after the first "flash," some times after more, the body of one of the two duellists was seen to fall upon its back to rise no more. And this process we watched repeated till on one side there were no antagonists forth coming, and then the liefeless bodies of the combatants were collected and the crowd of spectators who had watched the "main" with no disorder but with a kind of suppressed excitement, turned and departed ~ folding their tents," or rather collecting their materials together, "like the Arabs and silently stealing away-" Who they were or where they came from I know not, the only explanation I ever got was from some one who said, "They were gentlemen from Liverpool !"

Now it would be mere affectation to say that we schoolboys witnessed the sight with horror, as I suppose some would say we ought to have done, for we did'nt, for schoolboys are not born little humanitarians. All the same, there was a feeling somewhere in my heart or bowels, or wherever such felings are bred, that all was not right in such an exhibition. I remembered that we had an old gamecock at home who had either maimed or killed outright nearly all the other cocks in the parish, of which he thus became cock of the walk,' and instead of teading him lessons in morality, still less of putting him out of the way, we were rather proud of him, as he certainly was of himself, as the proud and ferocious twinkle of one eye (for, like Nelson, he had lost the other) only too plainly showed. But this was a different thing. All this bloodshed and slaughter was but in the way of Nature, and an exemplification of her laws as laid down by Darwin and others, But the sight of those flashing spurs—that somehow affected me, and so does the recollection of it now. So I pass on.

Douglas - Harris Promenade in Olden Days.

You say (and it is, indeed, an odd coincidence) me the rest of the field, how built upon, is called "Hutchinson Square." Of course, I take this as a pure "coincidence," but it reminds me that, in addition to the Hutchinsons mentioned in my former paper—Joanna and her brother Henry — "the retired mariner" of Wordsworth — there were other Hutchinsons of the same family residing upon the island, and, as they were all of them "interesting" persons, perhaps I may be allowed to say something of them. One, a cousin of the above-named and therefore of my father, was known as Henry of Peel. He was a shipowner, trading with the Baltic and generally commanded his own vessels. His house in Peel was a large red-bricked one, facing the centre of the beach and at the angle of the main street leading thereto. as he loved to be near the sound of his darling element. Also to see his yacht riding at anchor in the little bay. For he was one of the first, if not the very first, possessors of a yacht all to himself in the Island, and his delight was, with himself in command, a boy as mate, and his wife as passenger, to make excursions round the Island and elsewhere, and, on account of his affection to his "passenger," he called the little ship "The Henry and Eliza." It is quite possible that some tradition of it may exist in yachting circles in the Island to this day. If so, I should be glad to hear. The descendants at least of Peel sailors or fishermen may, perhaps, have heard of the little vessel and the tragic end it came to — foundering after a successful voyage in Peel bay, within sight — almost within reach — of it's owner's house, With its captain, crew, and passenger on board. Fortunately they were all saved, but the little vessel went to pieces, though its contents were salvaged by the zeal of the fisher folk of the town, by whom the owner was universally beloved. I have amongst my most valued Possessions a pair of silver "salts " Picked up green from the sea. Also I had, though these have long disappeared. a set of sandbags, used for stopping draughts through the little cabin windows, for "my cousin," as I call him, was a bad sleeper at home and often at night retired to his little vessel riding in the bay to be lulled to slumber by the lapping of the waves around his pillow, the little rope-like sandbags meanwhile protecting him from draughts, On my visit to the Island in 1872 (not in 1871, as stated by error in my last article), I remember a good woman with whom I got casually into conversation on the shore, telling me all this as to a stranger. You may guess I was gratified to find that my relative was so affectionately remembered, and when my informant found out who I was, I really believe she would have kissed me. Also, I think I would have let her, only my newly-married wife was standing by.

Mr. and Mrs. Hutchinson, taken when they last crossed in 1872,

But there was, strangely enough, a third Henry Hutchinson, dwelling on the Island, and also a "cousin.'"' He was always known as " Mr. Henry," as if that were his surname, and he lived in Douglas somewhere towards the land end of Athol-street. My interest in him centred chiefly in the fact that periodically I was expected to pay him a visit, on which occasion I invariably found him after an early dinner seated at his table with a decanter of port and something in the way of dessert before him. From the former he invariably poured out for me a glass of wine (limited), from the latter he heaped my plate (unlimited). The only variation from this rule was in summer. time, when, instead of the dessert, he handed me sixpence, telling me to go and spend it in fruit at a garden hard by whether this garden exists or not now I cannot say, but if not, if ought to, for it was a splendid one and admission to it was based on most business-like principles. You paid your sixpence at the gate and were allowed to "eat it out" in gooseberries, currants, or what ever fruit might be "on," (Mr. Gardener, however, taking care to turn you on where he had been first gleaner). In this way I thoroughly enjoyed myself, and having since that time read the "Adventures of Reynard the Fox," as told in the German version of that immortal story, I have often wondered how I managed to escape the fate of that most capable, but in this case short-sighted, beast, who, entering a larder by a hole just big enough to admit him, found, to his dismay, that the hole had grown too small to admit of his escape!

This gentleman's (my cousin's not Mr. Reynard's), hobbies were fishing and kite-flying. One day I remember his taking me with him up the little river which, I believe, finds its way into Douglas harbour, to teach me to throw a fly, but what was his surprise to find that I was already fairly proficient in that art, having acquired it long before I could repeat my "Hic, haec, hoe." His great ambition as a kite-flyer was to utilize the toy as an instrument of locomotion, for which purpose he attached its string to a light carriage in which when the winds served, he caused him self, sometimes successfully, to be drawn along the roads. More often he came to grief, and so came to be regarded as a crank. Nevertheless with the recollection of those gooseberry feasts and his general kindness strong upon me, I could wish there were more such "cranks" in the world

But if I have dwelt rather long — perhaps too long—upon " Mr Henry." it is that he was, as I come to look back upon things, typical of the class of person who, not being natives of the Island, made it their home and formed what was called the "society" of the Island—persons, I mean, of good family standing but of small, or what is generally called limited means, for there they could, as I have been informed, make a moderate income go nearly twice as far in all material comforts as in the adjoining Island of Great Britain, rent being lower and the duties on many articles of luxury — as French liquors, fruit, etc.. almost nil. Of course, this economical question did not affect me, yet it was brought home to me, I remember, in a manner which I have never forgotten by my going one day into a grocer's shop (it was somewhere near the harbour) and asking for a pennyworth of figs. In England, I know, I should have got one or two or, at the most three, for that insignificant coin, but to my surprise the good shopkeeper handed me a packet sufficient to make me feel ill, if anything in those happy days in the nature of fruits could have had that effect. So in what I may call "my day," Douglas was full of people of moderate but independent means, and this it is, I believe, which brought so many Hutchinsons there, and it is not inappropriate, therefore, that there should now be a Hutchinson Square there, though, perhaps, the particular square built on "the field" may have been called after a Hutchinson millionaire, though I have never heard of such a one. If there be one, he must be a very distant connection of mine indeed.

The Post Office (1840) as described. [Photo, Keg, Douglas]

Searching through some old letters the other day I came upon one addressed from Douglas the postage of which to this foreign country was marked 8d.! This reminded me of the primitive postal arrangements of the Island during my stay in it. Well do I remember what they were for my dear aunt was in the habit from her lofty watch tower in Athol-street of looking out for the Liverpool steamers which brought the mails and on the appearance of one in the bay, a messenger was generally dispatched to the Post Office in the town to see if there was anything for her in the bags. On some of these occasions I was this messenger, and I shall never forget the task which then devolved upon me. The office so- called, was a small, ordinary house in the centre of the town, by the side of which there was a narrow passage up which expectors of letters were compelled to force their way to a small opening, about the size of the ticket-window at a Modern railway station through which letters were handed out to those who asked for them. I believe I am right in saying there was no "delivery" in any other sense, for I never remember seeing a postman in the town, As all applicants for letters had to force their way up the narrow passage aforesaid, and, having received them, had to force their way back again into the street against the stream of incomers (there being no " entrance out," as the Irishman said, at the back) the reader may imagine what a scrimmage there was round the little "office" sometimes and what a chance a weakly messenge> would have in getting in and out of the cul de sac (for that the passage really was). Fortunately was pretty strong, and moreover rusé, and, there- fore, usually came out with the first, but even I was glad when I found an easier way of discharging my postal duties. And that came about in this way. The Post Office at this time was in charge of two ladies— real ladies, I believe, for it was an office then conferred by favour of the name of Greaves, and these ladies were known to my aunt, who Suggested to me that « perhaps if I called at the front door and mentioned her name and said that I came for letters for her, she would not be surprised if I got them without risking life and limb in the usual efforts to obtain them." This suggestion I did not fail to follow, and thus, ever after, not only had I no difficulty in setting the letters. but was often asked if I would like a piece of cake or other dainty, which (would you believe it) I hardly ever refused

.

A Bit of Old Douglas.

Photo, Keig, Douglas.

But fancy the postal affairs of Douglas being regulated in this primitive fashion now, and what I should like to know is what would the dear old ladies who handed me my letters, as a favour, at their modest front door, think of the palatial building which now (I understand) erects its head as H.M. Post Office? No doubt they would go into fits. But, dear old things, they did their duty graciously in their time, and I hope they are still by some affectionately remembered!

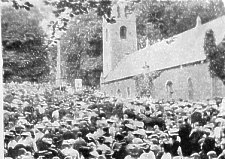

Kirk Braddan Church, where the late Mr. Henry Hutchinson is buried.

But, with the garrulity of age, I am running on to an unconscionable length. Long, however, as this paper may be, before closing it I should like to revert for a moment to the subject of my schoolboy recollections, and to "Old Imeson," as we were wont disrespectfully to speak of him, the first master of the "great Tom Brown " and little me. I have already said that I have quite forgiven the dear old boy for the whacking he once gave me as I think undeservedly. But not only so, through the long vista of some three score years, I now look back to the worthy old didasculus not only without animosity, but with actual affection. It is true that he would not be thought a model pedagogue in these fastidious times, for he had weaknesses, or at least one weakness, now generally considered unbecoming in one having the charge of ingenuous youth. To particularise, he was, to put it mildly, of a somewhat social disposition, and out of school hours was wont to resort too often to a certain house of entertainment near the quay and known, I believe, as the Pier Hotel, and one night returning home from some festive gathering there he lost his balance (so at least scandalmongers said) and fell into the harbour. I well remember now how we, his pupils, received the news with very mixed feelings, in which, I fear, sorrow did not alto- gether predominate, for the immediate con- sequences to us were a few days' holiday, pending his recovery from his dipping. O, the naughtiness of human nature in boys as well as men But it is not the remembrance of his thus conferring upon us involuntarily a happy time of freedom from tasks that was my chief cause of affection for him, but an incident which occurred on another occasion, which was this : I was in the habit on Sundays of accompanying my aunt to service at a church which stood near the harbour, but one for some reason I cannot recall, my aunt could not go, and I was sent by my own. On my way I remember I met a schoolfeliow, whom I persuaded to accompany me. Instead, however. of going into my aunt's pew, as we ought, we mounted into the gallery and found one there more to liking, for thence we had a better view of the congregation and felt more at home. It was a pew of the old-fashioned sort, with high sides and shut in by a door. There, all to ourselye; we followed the service, like good boys, until the sermon began. Then, one in each corner, we sat and listened. The discourse, however, not interesting us, we began gradually to get fidgety.

First we yawned, then we gazed at one another. Then we began,as by a common instinct, examining the contents of our pockets, which, by a most. singular coincidence, we found to contain chiefly marbles. Next and next —need I enumerate in detail all the steps of our \u2018facilis descensus Averni?" Nequaquam — by no means. Suffice it to say that in a short time we found ourselves down on our knees, not in prayer, but in an impromptu game of "ring taw" —and that in church! Think of that, ye godly! But think, also, of our con sternation when, on looking up, hearing some noise in the adjoining pew, we saw— O, the horror thrills me at this very moment—the solemn face of our master— "Old Imeson" to wit—gazing at us over the side of the pew! At first, I believe, we thought it was the "Old 'un" himself in the form of the worthy old man, come for us! But it wasn't—it was our "master" himself in propria persona, and I think our feeling was at the moment that we would rather it had been the "other one." Judge of our state of mind between that moment and that on the following day when me made appearance at school! I believe we neither us slept one moment in anticipation of what was in store for us. But—nothing happened! The dear old chap never referred to the incident although we fancied we saw a grim smile occa sionally on his countenance indicative of the fact that he had not forgotten it. But, as I say, he never referred to it, and for that reason, if no other, I regard him as one of the blessed. Reader, take off your hat to his memory:

|

|

||

| Part 1 Part 3 | ||

|

|

||

|

Any comments, errors or omissions gratefully received

The Editor |

||