[From The Manxman, #1 1911]

There was an old skipper, I don't know his name, Hieigh, Heigh ! Blow the man down !

At one time I almost intended to give a series of personal histories of all the Steam Packet captains from the start onwards, but, on second thought, I don't think this would do at all. The earlier ones, although some of them were tremendously famous, would alone take up two or three complete summer issues for several years. I have, therefore, come to the conclusion that I will deal with the past and the present masters just as something happens to make the subject topical.

I know I ought to begin at the beginning, but that would be most; inappropriate on this occasion. The real first captain was one Crawford, a worthy Scotsman, who, in 1828, was appointed master of the steamer Enterprise, which traded between Glasgow and Liverpool, calling occasionally at the Isle of Man. The compliment was paid to him by the original directors of the Isle of Man Steam Packet Company of the commandership of their first steamer, and he accepted it. But the canny Scot, thinking that, perhaps, the new, little company might not be regularly able to pay his wages (after superintending the building of the boat for a few months), gracefully resigned.

This action led the directors-who have always keen pretty wise men, just as they are to-day-to appoint William Gill, a Ramsey man, who had sailed, in an unrivalled way, the smacks and schooners of that period, and who had a practical knowledge, never afterwards surpassed, of the conditions of tides, winds, and currents between Liverpool and the Isle of .Man. It is not too much to say that he was a potent factor in the after success. But both elsewhere in this and in future issues I shall have much to say about Gill, who ultimately received a service of plate presented by the town of Liverpool.

I take it for granted all my readers know that Mr. Hall Caine publicly said that the (late) Rev. T. E. Brown was "the most famous Manxman living or dead." So he was. Well, " Tom " Brown wrote this with his own hand about, Captain Gill for me, and here it is:-

I think I knew all the old captains of the Isle of Man Steam Packet Company's service. Of course I began by looking up with humble reverence and admiration to these august persons. As time went on, and I was admitted to something like intimacy, I was still very chary of taking liberties with my captains. This does not prevent my seeing, and saying now, that they were grand old fellows. They differed in point of ability, of temper, of social aptness, and popular ways. But they were all of them men and gentlemen. It is remarkable that the service should have turned out a type of officer so uniformly courteous and efficient, The sea, we all know, has a natural tendency to produce magnanimity, courage, and generosity. But thus these qualities should have been so invariably combined in the case of men springing for the most part from the ranks; that one after another, as he succeeded to a post however honourable, should have done -both it and himself such ample justice is, to say the least, very noteworthy. One feels that it is something to be a Manx captain, and that to be a captain in the service of the Isle of Man Steam Packet Company-' is not far from a patent of nobility, I had almost said, by hereditary descent.

First comes Captain Gill, the discoverer of the Victoria Channel at the mouth of the Mersey. He was eminently a popular captain. Now-a-days a captain has hardly much chance to display popular qualities. "Exalted above the people," a silent demi-god, it is all he can do to guide his 2,000 tons of greased lightning safely and at headlong speed through the intricacies of river and channel navigation. Captain Gill occupied a very different place. There was a little dignity, but not over much, to be considered. A captain in those days could sit down and have a good coosh.. He could extend this, moreover, beyond the circle of his intimates and cronies, and include in his hearty welcome the ordinary passenger, the decent tripper, the homely Lancashire matron, the family group so merry and respectable. He could mark the son of an old friend. For instance, I remember his marking me. No doubt he made use of me, but that was all right, all in the way of business. My older readers will still retain affection, might I not say, pious associations with certain memories. Old Douglas worthies-their names spring spontaneously to our lips. Among them was Lieutenant G. H. Wood, soldier, poet, meta-physician, public reader and reciter, musician. A glorious morning in the old " Ben-my-chree " ; Mr. Wood was on board. Any one of his faculties, if applied at full force (and he was rather lavish in that respect), would have been quite enough to keep an honest sea-captain at the stretch, and seriously compromise, even in those days of slow security, the safety of the four or five hundred passengers. Mr. Wood had not brought with him his famous contra-basso, or he might have supplemented the band, consisting of three saxhorns and a clarionet. Mr. Wood was on the metaphysical lay, and he worried poor Captain Gill most unmercifully. The captain looked to me. I knew as much about metaphysics as an Oxford man in his second year is justified in knowingthat is, precisely nothing. But I could not resist the captain's appeal.

" Mr. Brown," said the captain, " I am terribly busy; would you mind talking with Lieutenant Wood here? Perhaps it's rather more in your line."

Then, turning to the old metaphysician, " A son of oul' Parson Brown's, sir." It was my first introduction.

Thank God, I have never had a difficulty in simulating knowledge, or in listening patiently. In a brace of shakes," we were right into the core of the Berkleian theory, nay, through it and out on the other side, pawing vacancy. Mr. Wood demonstrated that, except in imagination, there is no difference between the bow and the stern of a ship.

"Which is the bow?" he demanded fiercely. "How do you know?"

" Because, bet- well, of course, obviously because--"

" Nay, sir," said Mr. Wood, " no prevarication." And so we went on. The bow continued to be the bow, and the stern the stern, and the ship was saved.

I should like, with your permission, to return to the subject of " The Old Manx Captains " at an early date.

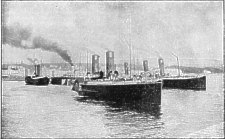

Present Day-Some of the Paddle Fleet at Douglas,

As the Manx captains are notoriously modest men we shall probably not say as much about them as we should like, or as they really deserve. However, it is but right that in this first number I should give some photographs of the living as well as the mighty dead, it being universally admitted that the late Capt. Gill, the first of all, was certainly fully equal to even the best which came after him. But to the living.

Captain Thomas Keig.

Captain Thomas Keig, the commander of the Ben-my-Chree, is the commodore of the fleet. He has spent many years of service with the old firm, and has been, at one time or another, in charge of most of their vessels. He has a positive genius for the work, and combines, with his great skill of seamanship, an extremely valuable and practical knowledge of the design and planning of a vessel. He is a most up-to-date man.

.

Captain Alec Reid.

Captain. Alec Reid, the master of the famous paddle boat Empress Queen, the largest and most powerful of this class ever built, is well-known to tens of thousands who do not know him. All said and done, a more popular or better liked man never took a Manx steamer across the Channel. He was, as it were, born into the Manx service, for his father, then one of the earliest chief engineers, took him across at the age of two. At one time he actually lived on the old wooden King Orry, which was built in. Douglas in 1840. Captain Reid is absolutely the very cheeriest and merriest of men, and every creature on the Island is proud of him. His services to the firm are self-evident to everybody.

|

|

||

|

|

||

|

Any comments, errors or omissions gratefully received

The Editor |

||