[J Manx Museum vol IV #63 pp199/202 - 1940]

For about four thousand years mankind has devoted much thought and labour to the cultivation of corn. Yet for half of that long period the only corn mills known were simple mortars or quern-stones laboriously worked by hand. Thus the invention, perhaps about 100 B.C., of a primitive water-mill was an outstanding advance on the slavish hand-mill and the event was fittingly commemorated by an ancient poet in a picturesque epigram :

Cease your work, ye maids, ye who laboured at the mill.

Sleep now, and let the birds sing to the ruddy morn.

Ceres has commanded the water-nymphs to perform your task;

And these, obedient to her call, throw themselves on the wheel,

Force round the axle-tree, and so the heavy mill. Antipater of Thessalonica 1

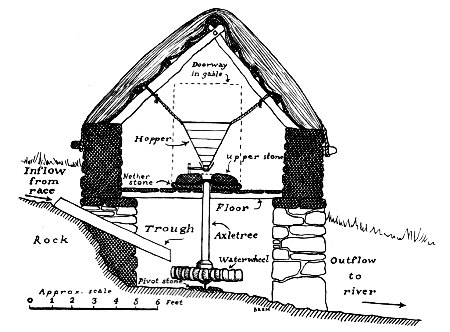

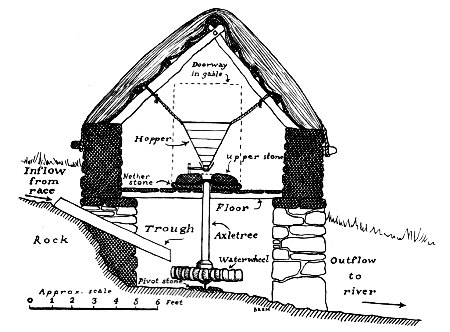

The type of water-mill here referred to is known as the Horizontal Mill, since the water-wheel lies horizontally at the lower end of an upright shaft or axle, instead ot vertically as in the case of the Roman or modern mill. A force of water is projected from a trough against the paddles of the wheel. 'The upper end of the shaft passes through the nether mill-stone, placed on the floor above, and engages the upper stone. Thus the water-wheel, the shaft and the upper stone all revolve together,2 see Plate 182. Horizontal mills have been employed until modern times by the peasantry of various parts of Europe including Rumania, Norway, and Shetland, as well as in China. Although unknown in England it is little more than a century since the type became obsolete in Ireland and the Isle of Man.

The earliest reference to the existence of the Horizontal Mill in the Isle of Man occurs in the following notice written by an Ulsterman at the close of the seventeenth century :

"In county Down issue many rills and streams, and on almost each of them a townland had a little miln for grinding oats. The milns are called Danish or ladle milns; the axel-tree stood upright, and ye small stones (or querns, such as are turned with hands) on ye top thereof. The water-wheel was fixed at ye lower end of ye axel-tree, and did run horizontally among ye water, a small force driving it. I have seen of them also in ye Isle - of Man, where the Danes domineered as well as here in Ireland, and left their custom behind them".3

But it is to Bishop Wilson that we owe the only account of the type as it existed in the Isle of Man: '"HorizontaL Mills. — Many of the rivers (or rather rivulets) not having water sufficient to drive a mill, the greatest part of the year, necessity has put them upon an invention of a. cheap sort of mill, which, as it costs very little, is no great loss, though it stands [idle] six months in the year; the water-wheel, about six 4 feet in diameter, lies horizontal, consisting of a great many hollow ladles, against which the water, brought down in a trough, strikes forcibly, and gives motion to the upper stone, which by a beam and iron is joined to the centre of the water- wheel; not but that they have other mills both for corn and fulling cloth, where they have water in summer more plentiful"5,

Thus it appears that about 1720 horizontal mills were numerous in the island, though Feltham wrote 70 years later that "they are now getting into disuse, probably from the late erection of large mills on the great streams. I only heard of two on this plan, which were said to be, one near Snugborough; the other in Baldon | Bald- win], near Cronk Rule."6

Apart from a very brief note recorded by Speaker Moore in 1887 no other writer seems to have touched on the subject of these highly interesting Manx mills. Without doubt Mr. Moore was quoting from some person familiar with the working of these mills when he wrote that : 'the same sort of mill was used in the Isle of Man and was called Mullin Laare or floor mill. There was no casing round the stone, and there was a peg in the stone which, at every revolution, struck the moveable spout attached to the hopper. This shook the corn down into it and the ground meal was swept up off the floor from under the stone.'7

The literary evidence quoted above is sufficiently definite to prove that such mills actually existed in the Island, but as descriptions these passages are all too brief. For four years repeated efforts have been made to collect further information on the subject — particularly with a view to recording any knowledge of these mills which might have survived in the memory of the oldest country people. These enquiries were seldom rewarded, but in three cases they bore fruit. Mr. Cubbon, of the Manx Museum, recalled that more than ten years previously the late Mr. John Cowley, formerly of Crammag, had shown him a place on the bank of one of the tributaries to the Sulby River, near Crammag, where he knew a little corn mill had existed many years ago. When Mr. Cubbon questioned the possibility of bringing grain up and down the steep broogh overlooking the place Mr. Cowley replied that the sacks of grain were carried on the backs of ponies. Although we had some difficulty in establishing the exact locality of this mill-site we were greatly assisted by the discovery of a place- name which the late P. M. C. Kermode had noted on his map of the area: 'Mullen [blank], Kion Arragh,' carefully marked as the name of a feature on the left bank of the Druidale River.8 Possibly Kermode was told the Manx name of the mill but forgot the descriptive element—hence the blank: as the names apply to the site of a mill,

Although no corn has been ground at the Druidale mill within living memory the Manorial Records in the Museum Library show that the owners of Druidale (Kirk Michael) continued to pay a shilling mill rent up to the year 1916 'for a Water Corn Mill in the Great River.' We find a record of this mill in the Composition Book compiled about 1750 (sometimes called the 'Manorial Roll, 1703'), which shows that 'William Cowley of Kk. Braddan and William Kelly, Kk. Michael' had been entered in the Lord's Rent Book 'ffor a new Watercorn Mill on the Great River rent 12d'; and the Liber Scaccarius for 1744 records the granting of the Governor's licence for the erection of their mill in that year. William Kelly was owner of Druidale, anciently known as Ary Horkell, or simply Nary, or the Airey (Wood's Atlas marks it as Airey Kelly). His partner in the mill was presumably one of the Cowleys of The Close, an intack farm embraced within the Kirk Braddan parish boundary, but connected with the neighbouring Druidale estate by a ford in the Sulby River immediately below the little corn-mill.

In point of fact there are at Druidale the foundations of two tiny little mills within a few yards of each other and served by the same race. The latter can still be followed along the whole length of its course, skirting the foot of the declivity until it rejoins the river below the buildings.

The upper mill is now nothing more than a square foundation measuring about eight feet internally. On the other hand the walls of the second building still stand as high as six feet in one section and, as proof that this was actually a corn and not a gorse-mill, we found parts of granite mill-stones, one built into the north wall, others lying below the masonry which had fallen into the centre. The mill has possessed two diminutive storeys, the lower one containing only the water wheel (which has entirely perished). The flow of water was no doubt directed against the paddles of the wheel from a trough projecting into the cellar through the west wall. The axle must have passed upward through a hole in a wooden floor, on which were the granite mill-stones. These were about three feet across, to judge from the frag- ments we found. The timbers of a low thatched roof would support a funnel-shaped hopper which slowly fed the grain into the aperture in the upper stone, but no trace of any wooden parts was found. Despite its present derelict condition this structure affords the best illustration of the appearance of the ancient mills of the island, and on this account it should certainly be preserved.

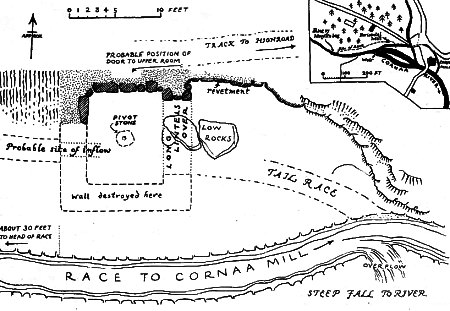

Mr. Gelling, whose father before him was miller at Cornaa, told us in 1937 of the remnants of a horizontal mill at the foot of Ballaglass Glen. In September of the present year, with Mr. Walter Gill, he kindly took us to the place and recounted all he knew of its former appearance. The site is near the head of the race which serves Mr. Gelling's mill, and he told us that when he first knew the little mill it was in a far more complete state. From his account and from what remains it is possible to reconstruct its general plan (Plate 182). The north wall still retains from four to six feet of its original height and is remarkable for the row of large boulders set vertically on edge (one more than three feet high) constituting the foundation of the structure. Among the smaller stones roughly laid in horizontal courses, without mortar, which form the upper part of the wall we noted at least two fragments of granite mill-stones.

The length of the building cannot now be ascertained by examination of the site as much of the structure (including 'long slate lintels') was removed during repair of the modern race, but Mr. Gelling states that the length was litle more than the breadth — he thought about ten feet. When it is realised that the existing north wall is less than eight feet long the diminutive character of the mill can readily be appreciated. The pivot or socket-stone on which the vertical axle9 revolved was found by Mr. Gelling embedded right in the middle of the floor, but it was unfortunately carried away by the flood of 1929. :

As regards the situation of the building, the north end was dug right into the slope of the river bank and what remains of the north wall serves as a revetment against the natural scarp. Very probably this was a gable wall with a door- way opening directly from the pathway on to the floor of the upper chamber about six feet above the foundations. The flat area to the east may also have been excavated from the slope, which is still retained in part by a revetment of dry-walling. On the other side, to the west of the mill, the line of the race can be discerned at intervals leading — as Mr. Gelling showed us — towards a derelict weir across the river where it is now spanned by a modern 'rustic' bridge. The pool caused by the weir is still known as Lhing ny Mwryllin-beg — 'the pond of the little mill.'

According to Mrs. Glass a plan of Ballaglass estate made in 1779, now owned by her brother, marks the little mill and a path leading to it from the road to the Lord's mill. We have not, however, succeeded in finding a record of the little mill in any of the Maughold Rent Books.

The sites of horizontal mills are still known at a few other places: near Ballacottier farm, in the Treen of Glenrushen and parish of Kirk Patrick, vestiges of Mwyllin y Sayle were still visible a few years ago. The late Mr. J. J. Kneen records a local description of it as a 'side-shot mill,'10 and Mr. Walter Gill draws our attention to Miss Morrison's version of an old tale about a fairy visit to the place which implies (he suggests) that the mill was in use when the tale was composed :

'went into hidlans in the daytime. One night, when he was out on his travels he came to Mullin Sayle, out in Glen Garragh.11 He saw a light in the mill, so he put his head through the open top half of the door to see what was going on inside, and there was Quaye Mooar's wife sifting corn .. '12

This tale may be fanciful in some respects but it preserves a genuine folk memory of the manner in which the little mills were used — there was no miller, the neighbouring farmers worked the mill on their own account at whatever time they required its services.

On the Narradale Stream bordering 'the Monk's Orchard' on Knockshamerk (Lezayre), Mr. Walter Gill tells us that he was shown the vestiges of a horizontal mill many years ago.

Many other such mills must have existed throughout the island, and it is more than likely that several gorse-bruising mills (ruins of which can be seen on many streams) mark the sites of horizontal corn-mills. When the latter were gradually falling into disuse at the end of the eighteenth century it may well be that some inventive farmer conceived the idea of using the water- power at his disposal to work his gorse mallets for him — just as, centuries earlier, some genius had devised the mechanism of the horizontal mill by using the force of a stream to turn his hand- quern.

That some of the gorse-mills occupy mill-sites far older than the eighteenth century is suggested by the fact that the Lonan parish boundary closely follows the course of a stream below Caunrhenny until it suddenly runs out a few yards on to the Conchan side of the stream at a point opposite the ruins of the Cooilroi gorse-mill. It seems to us that this slight deviation of the ancient boundary is designed to include within the Cooilroi estate that part of the right bank of the stream which was necessarily included in the area of the mill-pond.

The Norsemen knew the horizontal mill as kvern (compare our 'quern'), sometimes prefixed by the descriptive word skvett, referring to the squirt of water projected against the paddles of the wheel through a wooden spout or trough. Many places in Norway are still called after these old Kvernar, examples of which are used to this day.

That the same type of mill was in use in the Isle of Man in the days of its Norse kings is proved by the name Corna (=Kvern-a, 'mill-river'). by which the Santan burn is recorded in the Chronicon Manmae, and this is still the name of the river in Kirk Maughold on whose banks are the ruins of the horizontal mill we have described. The valley of this river is named Kurnadal (ie., Kvern-a dalr) in a runic inscription dating from the thirteenth century.13

The Treen of Carmodil, in Ballaugh, appears in all early records as Carnedall, or in some very similar form, and it may be assumed that the Carmodil River once supplied the power for one or more of these horizontal mills.£t

These Norse place-names prove that horizontal mills were well-established in the island at least by the thirteenth century, when the Norse dominion ended. It does not necessarily follow that the Norsemen introduced this type of mill to the island, although they may have been responsible for its introduction to Shetland where it is still known as the 'Norse Mill.'

That such mills were a regular feature of life in Celtic Ireland is clearly indicated by a passage in the ancient Brehon Laws,x and we have seen that they were known in Mediterranean lands centuries before the Viking Age. It is therefore quite possible that the Norsemen found these mills already in use when they came to settle in these islands more than a thousand years ago.

In this connection it may be noted that the Manx and Irish mills generally differed from the Shetland and Norwegian ones in possessing ladle- like instead of flat paddles. Again, in the former the lower end of the axle revolved on a pivot- stone fixed in the ground instead of on a moveable wooden lever by which the interval between the mill-stones was regulated. The Brehon Laws specifically mention ' the little stone which is under the head of the shaft and on which the shaft turns.x However, the lever mechanism of the 'Norse' mills is definitely ancient, the same principle being employed in an early type of hand quern which may possibly have suggested the origin of the horizontal mill itself in its homeland in the Near East. It may be that these distinctions are without much significance but, on the other hand, further research may establish that they represent two independent branches of development, the one Northern, the other Western.

Diagram of the mechanism of a Manx horizontal mill,

a drawing based on the vestiges at Druidale and Cornaa,

Bishop Wilson's description, and comparison with existing mills in Shetland.

See further article re important redescription of 'pivot stones'

Plan of site of the horizontal mill on the Cornaa River at the

foot of Ballaglass Glen.

Inset: Sketch of the neighbourhood showing the site of 'lhing ny mwyllin beg,'

the race and little mill.

(The road north of the little mill is the old road to the Lord's

mill.)

B..R. S. Mecaw.

1 Beckmann's translation, quoted by Bennett and Elton ' Hist. of Corn Milling,' II., p. 6.

2 Bennett and Elton, pp. 9-10.

3 'Montgomery MSS.,' c. 1698, fol. 321.

4 This figure must be wrong: the printer's eye may have wandered to the figure in the line above. Horizontal mill-wheels are generally about three feet in diameter.

5 Gibson's Camden's ' Britannia,' IT., p. 1448.

6 Feltham's 'Tour,' p. 123. The horizontal mills in Spain mentioned by Feltham were very likely derived from the type invented in Toulouse in the eighteenth century.

7 'Manx Note-Book,' III., p. 190.

8 Curiously enough, examination of the terrain showed that Mr. Kermode had

been misled by a quarry marked on the O.S. map, thus locating the name some

400 yards lower down the stream than the actual site. The slip is easily explained

and, fortunately, the nature of the land absolutely ruled out the possibility

of there ever having been a mill exactly at the place Kermode marked. Kion Arragh

is almost certainly intended tor Kione arrey — 'the head of the mill-race,'

1, the pond, or weir, in the river from which water was diverted to serve the

mill.

9 Mr. Gelling remembers the building as a ruin and only knows of the horizontal wheel with ladle- shaped paddles, the vertical axle, and the thatched roof by tradition through his father. He told us that another similar mill was situated further down the Cornaa River in 'the Dal Mooar,' and we noticed what may have been the last vestiges of the race against the broogh marked 1948 on 25" O.S. sheet VIII. 7.

10 "Place-Names," p. 359.

11 Mr. Gill gives the site as the foot of Glen Dhoo between Arrysey and Baliacottier.

12 'Manx Fairy Tales' (1929), p. 35.

13 J. J. Kneen, ' Place-Names,' p. 284-5, under Cardle.

14 Mr. Walter Gill acutely suggests that the Gaelic names 'Brow mullen a gresy,' 'the bank of the cobbler's mill' (Lonan, Composition Book, 1703), 'Mollen beg' (German, 1643), 'Mwyllin ny haash,' Mill of the people? (Lezayre, J. J. Kneen), may refer to mills owned by common folk rather than to official Lord's mills, and therefore may record the existence of horizontal mills at these places. We have already noticed that the Cornaa example was known as "Mwyllin beg." Manx Gaelic had no special term for the horizontal as opposed to any other type of mill, and they could only be distinguished by the use of descriptive adjectives. (It should be noted that 'Mullen beg' (Lonan) which Kneen quoted from the Composition Book, 1703, reads 'Nuilen beg' in the original manuscript.)

15 Quoted by Bennett and Elton, I, p. 90.

A subsequent article added further information, together with a reconsidered description of the pivot point of the vaned wheel - a reconsideration of the dismisal of Bishop Wilson's 6ft diamter might also be noted from an 1802 account.

SINCE 1940, when the mwyllin beg was first described in the Journal,1 some further information on the subject has become available. Two points are put on record here, as being of general interest.

The first item is a brief descriptive note by a Welsh surveyor and engineer, Lewis Morris, who had seen one of the Manx watermills with horizontal wheel about the year 1720— i.e., about the same time as Bishop Wilson wrote his description of the type. Morris's account, which was found by Mr Rhys Jenkins in a manuscript2 in the National Library of Wales, has the merit of being quite independent of the other descriptions and is, moreover, a concise record by a competent observer. Writing about 1740, Morris notes that: :

"About 20 years ago I observed a water mill near Douglas in ye Isle of Man done in a most simple natural manner as if Adam had been ye inventor. The house was built cross ye river. The millstone stood on ye end of ye principal beam on ye lower end of which was six leaves or wings on which the stream press'd. This it seems is ye most antient of all Inventions of this kind because most simple"

The location of this mill 'near Douglas' suggests that it was situated either on the Braddan or the Tromode branch of the Douglas river. If the former, as seems most likely in view of its proximity to the highway usually followed by travellers, it may well have been the mill 'at Snugboro' (near Union Mills) which Feltham referred to as still in being about 1790. The "six leaves or wings," comprising a horizontal wheel, were evidently flat wooden vanes like those of the 'Norse mills'' of Shetland and the Hebrides. The description would hardly apply to the 'great many hollow ladles' mentioned in Bishop Wilson's account of a Manx mill built on what seems to have been the usual Irish model.3

None of the descriptions of Manx examples explain how the foot of the vertical spindle, or wheel-shaft, was supported. In the 'Norse mill' the foot of the wheel-shaft is supported on an adjustable horizontal beam or lever, called the sole-tree, so that the shaft—and, with it, the upper millstone—can be raised or lowered. Thereby the interval between the millstones is increased or decreased as required. The Irish mills no longer exist, but vestiges and records which survive have been taken to show that they differed from the Norse mills not only in the form of the mill-wheel but also in that the upright wheel-shaft bore upon a rigid stone set in the ground under the mill. Dr Cecil Curwen's recent study 4 of vertical-shaft mills makes the existence of such a rudimentary and inefficient arrangement seem rather less certain than before. In any case we now have reason to believe that the flat-vaned type of waterwheel characteristic of the Norse mills was used in the Isle of Man (besides the Irish variety) so it is all the more likely that the moveable wheel-shaft was employed here also.5

Indeed, this now seems to be as good as proven in the case of the ruined mill at Druidale — which was erected during Bishop Wilson's lifetime. When a mass of fallen masonry was cleared from the interior of the ruin, in 1941, the original floor of the 'under-house' was found to be paved with long slate flags from wall to wall. There was no trace of a socket-stone on which the vertical wheel-shaft might have turned, nor was there any gap in the paving from whence such a bearing might have been removed. Therefore the lower end of the shaft clearly must have been supported by some form of wooden structure which, like the rest of the mechanism, had either rotted away or been removed when the building went out of use. There was no positive proof that the vanished supporting beam was a lever, as used in the Norse mills for adjusting the interval between the mill-stones: but there can be little doubt that it was so.

As pointed out in 1940 this method of supporting the vertical shaft is also found in an improved type of rotary quern or hand-mill, in which the device employed for raising or lowering the upper millstone is exactly the same. In theory, it would only be necessary to enlarge and attach vanes to the moveable spindle in order to convert this form of quern into the 'peasant' watermill with horizontal wheel. Since this special type of hand-mill was apparently in use —even in Britain and Ireland —within a few centuries of the first appearance of the rotary mill, it may well represent a stage in the development of the watermill from the prehistoric quern. 3 Two deductions follow, if this surmise is correct: the less important being that a lever to support the wheel-shaft is fundamental to the 'peasant' watermill.'7It also follows that, as Lewis Morris neatly said two hundred years ago, "this [mill] it seems is ye most antient of all Inventions of this kind because most simple.' That is to say, the humble mwyllin beg appears to represent the original type from which the Roman watermill evolved —and, through that, the modern mill with over- or under-shot wheel. Therefore, with its relatives in other lands, it occupies a unique position in the history of mechanical inventions.

1 B.R.S. Megaw "Journal of the Manx Museum," (Dec. 1940) Vol.IV,,

No: 63, pp199 ff

A supplementary lecture given to the I.M. Natural History & Antiquarian

Society in 1941 supplied fuller details, for instance of the Druiddale ruins,

and also described the gorse-mills driven by water-power; but circumstances

have caused its publication to be postponed.

2 Quoted in the discussion following 'The Shetland Watermill,' by M. W. Dickinson and E. Straker, in 'Transactions of the Newcomen Society,' XIII (1932-33), p. 89. ff. Sir William Ll. Davies, Librarian of the National Library of Wales, has kindly verified the quotation as given above, and states that it appears on page 183 of Morris's volume of miscellanea (N.L.W. MS 67 A.)

3 Some Scandinavian mills seem to resemble the Irish in so far as water-wheels with spoon-shaped vanes are said to occur in Norway and Sweden, aithough flat-vaned wheels are usual there. .Watermills of the same type, with spoon-shaped vanes, are found as far afield as Russia (east of the Volga) and Persia. 7

4 'The Problem of Early Watermills,' in 'Antiquity' — (Sept. 1944) No. 71, p. 130 ff.

5 The evidence concerning the original position of the lost socket or 'pivot-stone' from the ruined Cornaa mill is none too certain. The verbal account quoted in our previous article may have been coloured by the theories of local antiquarians familiar with such descriptions of the Irish mills as appear in Bennett and Elton's "History of Corn milling." However, there is no need to deny that a mill such as we described in 1940 could ever have existed: but, if it did exist, we should now incline to regard it as a degeneration from the normal type.

6 Mr. Curwen has drawn attention to one of these querns (which are recognisable by the hole through the centre of the lower stone) of the first century A.D., from Glastonbury; while Professor O' Riordain found examples at Cush, co. Limerick, which may be even earlier.

7 The use of the 'sole-tree' (the horizontal lever upon which the vertical wheel-shaft turns) is recorded from practically every area where the peasant watermill is found. Even in Kashmir there are mills, identical with those of Norway, in which 'a stone pivot under the axle turns in a horizontal log,'—the latter adjustable by wedges. (Cf. " Language Hunting in the Karakoram," by BK. O. Lorimer.)

|

|

||

|

|

||

| Any comments, errors or omissions gratefully received MNB

Editor HTML Transcription © F.Coakley , 2011 |

||