Tomb of Bronze Age

(Commonly called King Orry's Grave)

[From Isle of Man by John Quine, 1911]

[some further photos to be added]

The story of the human race on our island, or indeed elsewhere, may conveniently be divided into two periods the later, or Historic, in which written documents exist recording events of the past, a period beginning in Man with the introduction of Christianity; and the earlier, or Prehistoric, for a knowledge of which we have to depend upon the monuments, implements, and other relics of bygone peoples that have come down to us. We have already spoken of the Historic period, and shall therefore here treat only of the Prehistoric.

In the earliest stages of Man's existence he had no knowledge of how to work metals, and consequently had to depend mainly on stone for the simple implements which were necessary for everyday life. This epoch is known as the Stone Age.

Later, but only after he had made great advances in civilisation, primitive Man learnt how to smelt and mix the ores of copper and tin, and to make from them beautiful weapons and other implements of bronze. We therefore call this epoch the Bronze Age.

In time the difficulty of smelting iron was overcome, and the Iron Age began. All these Ages undoubtedly overlapped, and it should be noted that in some parts of the world no Bronze Age intervened between the Stone and the Iron, while in others, e.g. New Guinea, the Stone Age survives to the present day.

Of all these periods the longest in duration was certainly the Stone Age. It is impossible for us to assign a date to this, or indeed to any other of these epochs, but there is no doubt that Man was making stone implements tens, if not hundreds of thousands of years ago. Here it should be stated that there are two very definite and distinct divisions of the Stone Age in Britain - the Palaeolithic or Early, and the Neolithic or Later Stone Age, and there is little doubt that a vast gap of time separated the two. Palaeolithic Man, who apparently did not reach the north of England, existed when Britain formed part of the Continent, had extinct animals like the mammoth as his contemporaries, lived much in caves, cultivated no land and tamed no beasts, and made roughly-fashioned weapons of chipped flint. When Neolithic Man came later on the scene our land was insular and he found a climate much as now: he kept domestic animals, sowed crops, had learned to grind and polish his weapons, and was on the whole in a fairly advanced stage of rough civilisation.

The earliest remains of prehistoric man on the island are in the form of small flint flakes, scrapers, awls, arrow-heads, etc., found in considerable quantities in different localities from Kirk Bride to Kirk Christ Rushen, and sparsely here and there all over the country. Where found in large quantities they are overlaid by a surface soil, and rest on an older surface, e.g. near Ramsey, in Kirk Michael, near Peel, at Garwick in Kirk Lonan, and at Port St Mary. They all belong to the Neolithic period.

Of later date there are flint and greenstone axe-heads, some very large, found singly in various localities.

Of barrows of this period the remains are not con siderable. The lower parts of the island have for a long period been well cultivated, and agriculture has operated as a destructive force. But even over the Northern Plain traces survive of many barrows, locally called " cronks," that are of earlier date than those of the Bronze Age. A few exist in Kirk Lonan, with circular chambers of smallish stones set on edge, but with no trace of burial urns, quite different from the cronks definitely assignable to the Bronze period. Bow-and-Arrow Hedge on Snaefell seems to have been a camp of the Stone Age.

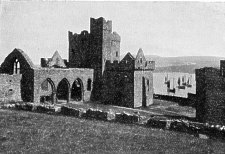

A few bronze celts, short leaf-shaped swords, and spear-heads have been found ; and there are many burial mounds of this period with urns, either large and rude with very rough ornamentation, or with cists formed of immense flags set on edge, with a flagstone lid, and con taining beautifully ornamented urns. In some cases the earth of the mound has been removed, leaving the stone Gist exposed, e.g. at King Orry's Grave near Laxey, and the Giant's Grave at St .Johns. There are also double cronks that seem to have been connected by a passage between large stones set on edge.

Tomb of Bronze Age

(Commonly called King Orry's Grave)

Of stone circles there are several of different types.The finest are on the Mull Hills near Spanish Head, at Glen Darragh, Oatlands, King Orry's Grave, Cregneish, Cloven Stones, and on the heights near Sulby. Near Port St Mary are several large monoliths that appear to be a fragment of a work of the Stonehenge class ; and single menhirs or standing stones are of frequent occurrence, but there is no example of a dolmen, such as may be found in Ireland and Anglesey. Cup-marked stones, supposed to be sacrificial, are found at Kirk Michael, Kirk Braddan, and at Oatlands in Kirk Santon.

The Cloven Stones

The Bow-and-Arrow Hedge consists of a trench and rampart crossing the ridge between two glens on the west skirt of Snaefell, evidently intended to protect a tribal camp. There is a large earthwork also on the east skirt of Snaefell overlooking Laxey, with several circular lines of mound within its area.

Many earthwork forts are found on the coast, but they seem to belong to a later, though very remote period. At latest they were of the Celtic period, though probably seized and strengthened by the Danes in the ninth century.

Stone Circle at Cregneish

The embankments and trenches at How Ingren, on the east bank of the Silverburn, opposite Castle Rushen, the seat of Godred Crovan, and of Olaf I in the first half of the twelfth century-while occupied by the Danes and doubtless strengthened by them-must have been, by reason of the natural position, a stronghold of much earlier origin. It is impossible not to think that it may be, not only of prehistoric origin, but in fact coeval with the very earliest occupation of the district by man. :And the same remark applies to St Patrick's Isle, to the earthworks of Cronk Sumark at Sulby, the rocky knolls of Castle ward and Glen Garwick, as also to the Black Fort and the alignments at Kirk Braddan. Fort Island has also a circular embankment, now sunk almost to the level of the even surface of the islet, that bespeaks an antiquity of pre-Celtic times. There are several of the same type in the inland parts of the island, and this type is quite distinct from that of Kirk Braddan and the Black Fort.

There are some traces of what seem to have been crannogs or lake-dwellings in Kirk Andreas and Kirk Marown. A fine canoe, dug or burnt out of a single oak tree, was found some years ago near the brows of the cliff between Peel and Kirk Michael, probably of a period when the sea stood at a much higher level than at present. There have also been found under the peat in various turbaries not only tree trunks, but logs with clear trace of rude adze-work. A well-shaped stone axe-head was found in a turbary in Ballaugh.

To prehistoric times in a sense belong also the stones with Ogam inscriptions found in a burial-ground near Port St Mary and in the burial-ground of the Friary at Kirk Arbory, but their period is within the Christian era. At Santon was found a stone with a debased Latin inscription, and with this and the earliest crosses may be said to begin the dawn of history on the island. It is not easy to assign a date to many rudely-worked stones in the Museum at Castle Rushen, some of which seem to have been sinkers for fishing nets; rude troughs in which to pound corn, earlier than the querns or stone hand-mills of which there are also many examples of less or more elaborate types; white pebbles placed in the graves of the dead, and others of uncertain use.

The "keills" or small churches of rough stone and turf, surrounded by an oval rampart of earth, and each provided with a small altar built of rubble, form a very interesting class of vestiges of Celtic times. Around these keills have been found stones incised with simple and rude crosses. In connection with Old Lonan church is a well, formed of slabs set on edge to form a triangular basin. It is supposed to have been a baptismal well, of a period prior to the introduction of fonts.

The ancient roads of the island are interesting in their relation to prehistoric times. Considerable stretches of them survive as by-roads, that could be used at most only for pack-horse traffic. They went straight down and up in order to cross glens, and it is probable that they followed the routes of track-ways of prehistoric times. From the occurrence of the names -gat, -gate (Danish, Bata =road), and -wath, -vad, -wat, -way (Danish, vad =ford or wading-place) on these old routes, they are definitely as old as Danish times as least; and from their position they must have been the routes from one district to another in the remotest past.

Another class of disused roads are the turf-roads from the mountains to the lowlands, and cross-country church and funeral paths, by the sides of which still survive examples of "croshes" or mounds on which the bier was rested, and where there was probably a cross. But these and the "mill-roads" come down to a period more properly called historic.

Of ecclesiastical architecture of definite styles, viz. Saxcn, Norman, Early English, Decorated, and Perpendicular, very few examples exist on the island, and none of very fine quality. The only Manx church with pretension to definite style is St German's Cathedral on St Patrick's Isle at Peel. The choir, dating from 1193, is of Transition or Late Norman; and was originally a Cistercian building, of the same character as the abbeys of Inch and Grey in County Down, Ireland. The nave and transepts are Early English, built by Bishop Symon, previously Abbot of Iona, and its whole shows a remarkable resemblance to the Iona church. Decorated windows were subsequently inserted in the transepts, and there are some Perpendicular fragments in the south side of the nave. The cathedral seems to have fallen into decay after the Reformation. It was last used in 1755, and by the end of the eighteenth century had become wholly roofless. The ruined church of St Patrick, with the base and door way of an Irish Round Tower, also stand on St Patrick's Isle: their date is not later than the eleventh century, and possibly as early as the tenth century. The modern chapel of Bishopscourt, eight miles away, is the present pro-cathedral; the only part of Bishopscourt that is ancient being a square thirteenth century tower, originally a stronghold surrounded by a moat.

St German's Cathedral, Peel Castle |

St Patrick's Church and Round Tower looking West on St Patrick's Isle |

There are, however, many evidences of ecclesiastical architecture that once existed on the island. Kirk Maughold parish church, the only Manx parish church of early date, has several Early English windows, and also parts of a Norman doorway and other fragments of Norman work, evidently vestiges of an earlier church on the present site.

All the eight parish churches on the western side of the island have been rebuilt in the nineteenth century, and only two of the old churches left standing, viz. Ballaugh, and St Peter's at Peel. On the eastern side of the island, of the nine parish churches four were rebuilt in the eighteenth century, four in the nineteenth, and Kirk Maughold merely restored. But the older churches of Lonan, Braddan, and Marown were left standing, and still continue to some degree in use and in repair.

Maughold Church

The parish churches of the island, on the evidence of that of Kirk Maughold and of the other five mentioned, were in structure a simple oblong, and the architectural features and ornament in no degree elaborate. Old Lonan has some parts of its masonry extremely early, and has a window and doorway of the thirteenth century. Old Marown is a rude and very early church, with massive walls, but no features indicative of its probable period. Old Braddan is of uncertain date, with an eighteenth century tower; but is especially interesting as containing many fragments of Norman mouldings on stones re-used as quoins in its doors and windows. Of Old Ballaugh and St Peter's, Peel, it may be said that they were pre-Reformation; but at various times they were so altered by the insertion of new windows by local masons, that all early features have been obliterated.

Old Church, Ballaugh

The Irish Round Tower, and parts of the walls of St Patrick's church on Peel islet, as already stated, are both very early work. The Round Tower stands in the usual position, a few yards distant from the west door' of the church. It must at some time have fallen into ruin to within 20 feet of the base; for above that height it is evidently rebuilt, and carried up, not with a slight batter, but vertically in cylindrical form. The doorway is much narrower at the spring of the arch than at the base; and this "Irish" characteristic, as well as the fact that the sill of the doorway is about seven feet above the ground, are the chief features that indicate its original form as a true Irish Round Tower.

St Patrick's church has its west gable fallen in a mass of ruin. The building was lengthened eastwards, so that it is impossible to form an idea of its original east gable. There were no windows in the north wall, and probably but one in the south wall. There are string courses of herring-bone work on the interior faces of its walls. What remains is in fact a fragment, from which the original "features" have been broken away.

St Trinian's ruined church, midway between Douglas and Peel, once the barony church of the baronial lands belonging to the Priory of Whithorn in Galloway, granted to that religious house about 1215, is mainly of that date or a little later. But it contains many fragments of Irish Norman work, evidently of an older church that stood on the same site. Within the church, at some depth beneath the floor, a cross has been found, carved on a slate slab used as covering slab to a stone grave: the date of the cross being probably not later than the seventh century. There is thus reason to believe that the site of St Trinian's, as a religious place, goes back to the seventh century.

In general there survive very many ancient Christian burial grounds on the island, each with some vestiges of a very small church built of rough rubble and sod; but with architectural features, so far as any exist, only of the very rudest character. They belong to the period prior to the Danish settlements, namely before A.D. 800. These little churches, to which we have already alluded, are called sometimes " keills," and sometimes "treen churches," from an impression that there was one on each treen or estate. It is generally accepted that they fell into disuse in the twelfth century, when, under the kings of Godred Crovan's dynasty, the parochial system with parish churches became the ecclesiastical system on the island: but it is also probable that the keill burial-grounds continued to be the burial-place of local families for a considerable period after the keill itself had fallen into disuse.

Architecturally the Isle of Man was never rich in the quality of its buildings for religious purposes; but, if the expression may be used, it was rich in the number of them. What architectural features existed seem to have been due to the monastic orders; but even Rushen Abbey, which was well endowed with lands, did not possess buildings of a character corresponding to its wealth and territorial influence.

Rushen Abbey

To recapitulate, there are Norman fragments at Kirk Braddan, Kirk Maughold, and St Trinian's: the ruined church of St Patrick also once had Irish Norman details, and there is a little fragment of Norman work at Jurby. The chancel of St German's Cathedral is Transition or Early Pointed, and the ruined chapel on St Michael's islet is probably of the same period. There is Early English work at St German's, Kirk Maughold, Old Kirk Lonan, the Nunnery near Douglas, Rushen Abbey, and St Trinian's; and at St German's there is some Decorated and some Perpendicular work. For the rest there survives nothing strictly architectural in the existing ecclesiastical buildings of the island-if we omit some recent churches, viz..at Peel, Kirk Braddan, and in Douglas: these being in a different category, as buildings in no way characteristic of the Isle of Man.

The Manx churches rebuilt in the eighteenth century were all simple oblong buildings, of the plainest descrip tion, the work of local masons, who attempted nothing beyond a plain circular arch absolutely without ornament; had no scruple about using runic crosses for lintels over doorways ; and showed no respect for older work when they altered or enlarged a building.

Of the earliest sort of fortification, the earthwork of prehistoric times, many vestiges are found throughout the island ; several in each of the 17 parishes. But as some of them have been nearly levelled out by the plough, or used as material for the sod fences which are the sort usual throughout the island, there remain only about 50 with definite details.

Some of them are no doubt of the pre-Celtic period, some the forts of the Celtic clans, and some Danish camps or strongholds. The Bow-and-Arrow Hedge, which we have already mentioned, is a great dyke with ditch, lying across between two glens, to defend a camp on the ridge below the dyke. This work is generally under stood to be of very early origin, and flint flakes found on the dyke imply that it was probably pre-Celtic. Another like alignment, with massive upright stones which seem to have served as a backbone to the earth dyke, defends a ridge over Laxey valley. South Barule is crowned by a large fort, which, from its character, may also be of the same early period.

On the two rocky eminences of Cronk Sumark at Sulby are two earth forts which are of a different character and are supposed to be of the Celtic period. Others of this type crown rocky eminences in Gatwick Glen and at Castleward near Douglas.

The prefix cot- occurs in many Manx names of places where vestiges of considerable forts still survive : it is probably the Irish cahir (=fort) ; and it is assumed that these forts were Celtic. But naturally, when the island was seized by Danish immigrants in the ninth century, these forts may have become Danish strongholds.

The most important Danish sites are at How Ingren, across the river from Castle Rushen at the mouth of the Silverburn; the earthwork within Peel Castle on St Patrick's Isle; the Black Fort, near St Mark's; Cronk Moar, near Port Erin; the alignments at Kirk Braddan; the banks and trenches at Fort Island; and the earthwork on the brows immediately north of Ramsey.

How Ingren was the residence of Godred Crovan, who conquered Man in 1076. Magnus Barefoot of Norway conquered the Isles in 1095, and made Man his place of residence and a centre for expeditions. He erected strongholds, for which he obliged the men of Galloway to provide timber for the stockades on the earth ramparts. It is probable, in fact, that he seized already existing places and strengthened them. The traditional name of the estate on which the Black Fort stands is Cornaman (Caer-na-magn = the fort of Magnus), thus identifying the Black Fort as one of these. It is probable that he also strengthened St Patrick's Isle, where he is known to have landed; also the stronghold at Braddan, and another, now destroyed, at Ramsey.

When Somerled landed at Ramsey (1164), Maughold churchyard was the retreat of the people of the country; and their cattle were also driven within the enclosure. When Godred II died at St Patrick's Isle in 1187, it may be assumed that a stronghold existed there; but there is no evidence that there was any building of stone.

Bishopscourt Tower is of the thirteenth century, and was probably built by Bishop Symon. It is mentioned as occupied by Cospatric, an officer of the King of Norway, who seized Man in 1240. This tower, with Castle Rushen and Peel Castle, are the only castles on the island; though the gatehouse of Rushen Abbey, which had the right of bayle, bailey, or protection by wall and tower, may also be included in this class of work.

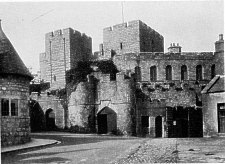

Castle Rushen is first mentioned as occupied by Magnus, the last King of Man, in 1266. The earliest existing military architecture at Peel Castle probably dates from the time of Bishop Mark (1275). He was the first Scottish bishop when the island came under Scottish rule, and the work is characteristically Scottish in style.

Castle Rushen has a central tower or keep 80 feet high, possibly as early as the time of King Magnus: this tower was subsequently enlarged, not later than the fourteenth century. A second tower stands by the harbour ; and from this lesser tower a curtain wall, with seven small towers, encircles the inner court around the central keep. Outside the curtain is a moat, and around this moat a glacis dating from 1525.

Rushen Castle, Castletown

The castle was held in 1313 for the Comyn cause by Duncan McDougal of the Isles; but surrendered to King Robert Bruce. In 1651 the Countess of Derby was placed in a state of siege in the castle by the Manx militia under William Christian; and surrendered on the arrival of the Parliament troops under Colonel Ducken field. It became the insular gaol, as well as seat of administration during the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, till Castletown ceased to be the capital of the island. The most famous of its prisoners was Bishop Wilson, who was imprisoned in 1722 by an arbitrary act of the then Governor. The castle is built of hard grey limestone, of a singularly durable sort; and the castle, now a show place, is in a state of perfect repair.

Peel Castle

Peel Castle is of a quite different type: it covers a large area, viz. about five acres within the cliffs of St Patrick's Isle; and its strength consisted in the great curtain wall surrounding the whole. On the harbour side is a three-storied tower or peel, of Scottish type, from which Peel derived its name. The east gable of St German's Cathedral is flush with the castle wall and forms at that point part of the fortifications. Peel Castle, like St German's Cathedral, is a ruin. Under the cathedral was the ecclesiastical prison of the Bishops of Sodor and Man. The castle, which was the residence of the Earl of Warwick in the reign of Richard 11, was taken by the Manx militia under Captain Radcliffe in the rising of 1651. A famous prisoner was Captain Edward Christian, Governor of the island, whose attempt to bring the people over to the cause of the Parliament ended in his being confined here till his death. A garrison was maintained in the castle till 1736, when it was disbanded by the Duke of Athol. Peel Castle is now a show place. It is approached by a ferry across the harbour, and also by a causeway which at the beginning of the nineteenth century was constructed to join St Patrick's Isle to Knockaloe Hill and form a protection to Peel Harbour.

The Stanley Lords of Man had their seats at Lathom House and Knowsley in Lancashire. Castle Rushen and Peel Castle, the two "houses," as it was customary to call them, were garrisons and centres of administration; and Derby House, built within Castle Rushen, was the residence of Earl James only from 1644 to 1651 ; and then an asylum rather than residence.

In order to comprehend why the island has neither manor house nor hall, much less any great seat, it is necessary to understand the sort of estates held by the hereditary Manx proprietors. The Chronicle of Man and the Isles, written in the thirteenth and fourteenth centuries, frequently mentions the "chiefs" and "mag nates" of Man, who were evidently holders of estates. The earliest record of actual estates and their owners is a Rent Roll of 15 1 1 : a catalogue of " treens" of land, the owners, and the rentals. The "treens" were ancient unit estates, ranging in area from something short of 1000 acres down to 150 acres. It is implied by many of the treen place-names, e.g. Ivar-statt (the stead of Ivar), Asmund-garth (the garth of Asmund), that these were unit estates during the Danish period, if not of even older origin. The "chiefs" and "magnates" seem to have been treen-holders, holding direct from the King of Man, and this limitation of estate-from 1000 to 150 acres-defines the class of Manx freeholders of the earlier times, down to the thirteenth century.

In the Rent Roll of 1511 only a few persons are found holding complete treens; many hold half-treens; the majority hold only a "quartron" of land; and there are others holding a "half-quartron," or even less. The "quartrons" varied in area from 250 to 50 acres; and a treen might contain six, five, or any less number of quartrons. This system of all tenants, greater and lesser, holding direct from the Lord, as found in the Rent Roll of 1511, has obtained ever since, with a definiteness that shows no essential change.

The absence of proprietors holding more than 1000 acres, the fact that the majority held about 100 acres, and that even the wealthiest men were of limited means, explains the absence of domestic architecture other than moderate mansion houses, farmhouses, and cottages. Even the revenue of the Bishop of Man in the reign of Queen Elizabeth did not enable him to keep Bishopscourt, such as it then was, in a reasonable state of repair" scarcely ever exceeding £100."

Bishopscourt, on the boundary of the parishes of Kirk Michael and Ballaugh, has been the residence of the bishops from the time of Bishop Symon (1230). The original building was a square tower surrounded by a moat, on the lower margin of the Bishop's demesne of 600 acres: the other lands of his barony lying in the parishes of Patrick, German, and Jurby on the west side of the island, in Marown in the centre, and in Braddan on the east side.

The moat has been filled up, and the house enlarged by successive additions westward: the old tower, the chapel, and the Convocation hall being at the east end. It is a plain house, with no architectural pretensions, but picturesque by reason of the additions having been made at successive periods without uniformity of plan.

Every rectory and vicarage house on the island has been rebuilt within the past century. The same may be said of the mansions and farmhouses. Such country residences as exist in the neighbourhoods of Douglas, Castletown, Peel, and Ramsey are all of a comparatively recent period, and have no features specially characteristic of the island.

Nevertheless a few houses of older date survive. The farm buildings of Ballamanagh (= monks' farm) at Sulby, adjoining the Graingey (= granary) on the abbey lands, are evidently of great age, with features that indicate that they are of pre-Reformation date. The old farmhouse of Dollagh in Ballaugh is probably not later than the sixteenth century; and a later house on the same estate can be definitely assigned to the seventeenth century. In every parish a few farmhouses survive of at least 200 years old: the type is uniform, and the prototype of them all the simple two-storied house on St Patrick's Isle in the enclosure immediately north of the cathedral, traditionally known as the "Bishop's Palace."

All these old farmhouses are of slaty schist rubble, and the walls smooth with successive coats of lime white wash. The same type of house is found in the older streets of the towns.

It was customary in earlier times, when a new farmhouse was built, to use the old house as a barn or cowhouse; and in several instances-e.g. in Andreas, in Braddan, and Rushen-three and even four successive houses stand on the same homestead. There is scarcely an instance of a smaller house being added to and enlarged.

In the early part of the eighteenth century, during the prosperous times of the smuggling trade, a much larger class of house was built in the towns by the mer chant class, and in the country by the larger proprietors. Examples of these houses of merchants exist at Peel with fine vaulted cellars underneath, opening to the harbour; also in the older parts of Douglas, Ramsey, and Castle town. Indeed, in all these cases the cellars are a feature of the buildings. Of country houses of that period the type is sometimes three-storied, with five windows in length, e.g. Balnahawin House, bearing the date 1728, still standing near Tynwald Hill; the Hills House outside Douglas; and Balladoole House near Castletown. Another type is two-storied, and seven windows in length; e.g. Knockaloe House near Peel, and Balla brooie House at Sulby. Ronaldsway House, of the former type, with vaults underneath, seems to have older parts incorporated with it.

The Manx farmhouse of the eighteenth century is represented by many examples: all two-storied, and three windows in length; not in itself picturesque but, the white walls and grey slate roof softened by a century and a half of weathering, very seemly in the setting of its farmyard environment.

The Manx cottage, and often the lesser sort of farm house, was thatched: the thatch roped with a network of straw rope, made fast to projecting stones under the eaves, purposely fixed for the loops of the roping (see p. 141/g). On the Northern Plain, and at one time pro bably all over the island, the cottages were built of sod. A few of these may still be seen in Jurby, Andreas, and Bride. Turf was the fuel; the fireplace a large hearth stone against the gable wall, part of which was built of stone for this purpose; and the chimney broad and open. There are no inns of early date. Tithe barns once existed; but only the sites are identifiable. Of buildings other than houses, there survive a group of well-built warehouses on the west shore of Derbyhaven, supposed to have belonged to the Earl of Derby in the seventeenth century; and on the shore of Castletown Bay a building known as the "Big Cellar" in part at least dating from before the Reformation, its use evidently a warehouse. Both these buildings are now barns. As the "Big Cellar" was on the abbey land, and Rushen Abbey had right of toll, wreck, and bayle on the shore of Castletown Bay, this building is supposed to have been the Abbey import and export warehouse. The corn-mills on the Manx streams are always picturesque: but none of them seem to be of earlier date than the eighteenth century.

Cottages at Sulby

Castle Mona, which stands on a low sandy terrace, backed by wooded brows, in the middle of the crescent of Douglas Bay, was the residence of the last Duke of Athol, who was Lord of Man. The house was built in 1802, and is said to have cost £10,000. It forms three sides of a square, with a round battlemented tower occupying the fourth or landward side. The material is white freestone brought from Arran. The Duke occupied the house for about 25 years, and on his ceasing to reside on the island, the castle became an hotel. The formerly exten sive grounds have been long occupied by boarding-houses, and by "The Palace," an immense dancing and concert hall, which has the first place among the watering-place amusements of the Douglas visiting season.

Government House, the residence of the Lieutenant Governor, stands half a mile back from the heights of Douglas Bay. It is a modern extension of a somewhat less modern country house, rendered sufficiently spacious as a residence and with good reception rooms, but architecturally quite unpretentious.

In conclusion it may be said that with the exception of the few eighteenth century mansions already mentioned, and the single exception of Bishopscourt, the island has no domestic architecture of special interest.

Of interest transcending all other vestiges of human activity in the past of the Isle of Man are the Manx crosses, which survive from different periods between the sixth and the thirteenth centuries. There are in all over 120-of which about 80 are classed as pre-Scandinavian or Celtic, and 45 as Scandinavian. At least one example has been found in every parish in the island.

They are least numerous in the four southern parishes, Kirk Christ Rushen, Kirk Arbory, Kirk Malew, and Kirk Santon, and it has been suggested that the Cistercian monks of Rushen Abbey destroyed the old crosses in these parishes, which were in the neighbourhood of the abbey, with the advowsons in the abbey's gift. There are 37 crosses in the parish of Kirk Maughold alone; and of these 30 are pre-Scandinavian, and seven Scandinavian. As the crosses probably extend over a period of seven centuries, the total number surviving no doubt represents but a small proportion of those erected during that long period. The northern district has 75, as compared with 45 in the southern district: Kirk Maughold, though on the eastern side of the mountain range, being regarded as definitely in the north of the island.

Reckoning the eastern side of the mountain first, the crosses occur as follows:-Kirk Christ Rushen, 5 ; Kirk Arbory, 2; Kirk Malew, 3 ; Kirk Santon, 3 ; Kirk Braddan, 9; Kirk Marown (the one inland parish), 5; Kirk Onchan, 6; Kirk Lonan, 7; Kirk Maughold, 37 -giving a total of 77. On the western side of the island:-Kirk Patrick, 5 ; Kirk German, 7 ; Kirk Michael, 10 ; Ballaugh, 1 ; Jurby, 8 ; Kirk Christ Lezayre, 1 ; Kirk Andreas, 7 ; and Kirk Bride, 4-giving a total of 43. Some additional fragments recently discovered make a complete total for the island of over 120.

Of the pre-Scandinavian crosses, about 8o in number, only eight have inscriptions; but of the 45 Scandinavian crosses, 26 have runic inscriptions, and 1g ornament only. The central feature of the design is invariably a cross. Generally the Manx crosses are simple oblong slabs of blue slaty stone, with the ornament in relief, sometimes on one side of the slab, but more commonly on both sides. Between the earlier and later crosses a distinction can generally be made in the method of cutting the ornament: in the earlier it was by picking, either with a pointed hammer, or with hammer and pointed chisel; in the later examples with a hammer and a broader chisel with a cutting edge.

Cross at Kirk Lonan

It is clear that, in some cases, crosses of an older period were taken by the Scandinavian inhabitants of Man, and dressed along the edge, with part of the design on the face cut away, to obtain a smooth band for a runic in scription; and in other cases the ornament was chiselled away from part of the face of the cross, in order to have a smooth panel on which to cut the inscription. But some of the finest crosses are throughout of unmistakable Scandinavian workmanship. From these later examples it can be seen that the legendary old Norse mythology was fresh in the minds of the Danish Manx: in several instances these legends are depicted in the sculptures, which, though carved in low relief, are nevertheless wonderfully clear and definite in their subjects.

The earliest crosses, some of which may have been made in the sixth century, are extremely simple and rude, merely the cross in line, or a cross surrounded by a circle. A slab of blue slate found in the bottom of a well at Old Lonan church, supposed to be a baptismal well of a period anterior to the use of fonts, had a linear cross on one face, and a linear cross surrounded by a circle on the other. A gradual development and advance in workmanship can be traced in these early crosses, from the simple incised cross and circle to the great wheel crosses at Old Lonan and Kirk Braddan.

The traces of Anglian influence are apparent in the less early examples, and there can hardly be a doubt but that Man was to some degree influenced by Northumbria, though earlier theories were advanced on the hypothesis that the island was influenced mainly or even exclusively by Ireland and the Christian missions from the west. Anglian runes are definitely represented in the inscrip tions, harmonising with the historical records connecting Northumbria with Man in both the Saxon and Danish periods of that northern English kingdom.

The character of the inscriptions may be inferred from the following examples. Kirk Andreas: "Sandulf the Black raised this cross to Arinbjörg his wife." Kirk Michael: ",Joulfr, son of Thorolf the Red, raised this cross to Fritha his mother." Kirk Braddan : "Thorleif Hnakki raised this cross to Fiac his son, nephew of Hafr. Jesus." Ballaugh: "Olaf Liwtulfson raised this cross to Ulf his son." Kirk Bride: " Druian, son of Dugald, raised this cross to Athmoil his wife." Kirk German (St John's) : (a fragment) " ... but Asrathr raised these runes." One of the crosses at Kirk Michael has in addition to the usual formula the proverbial saying, "Better is it to leave a good foster-son than a bad son." On another Kirk Michael cross there is added "Gaut made this and all in Man." From this it is inferred that Gaut was the carver of all the Scandinavian crosses, and the idea is supported to some degree by part of an inscription on a Kirk Andreas cross, "but Gaut Björnson of Cooley made it'." There are, however, inscriptions professing to be carved by Osruth, Thurith, and John the Priest; and it seems as if there was one Thorbjørn who also carved runes. That "Gaut made all in Man" is, however, less interesting than the fact that the name "Man" occurs in the Scandinavian or Norse form "Maun"-precisely the pro nunciation of the word to this day among Manx people in the northern parishes.

It may be mentioned in conclusion that while the crosses are now carefully protected, each set at the parish church of the parish in which they have been found, a complete set of casts of all the crosses occupies a room in the Museum at Castle Rushen, where the student can study them, each in detail and in its relation to others of the same type.

Quite distinct from the above, and later by two cen turies than the latest of the Scandinavian crosses, is the beautiful late fourteenth century or Decorated parish cross which stands outside the gate of Kirk Maughold church yard. It is the only survival of the parish, or market crosses, of which there was probably one in every parish in the island, though perhaps nowhere so fine a one as this. Of others only the tradition survives in some half-dozen parishes. As the advowson of Kirk Maughold belonged to Furness Abbey, and the Priory of St Bees had also estates in this parish, the erection of this cross may have been the act of one or other of these religious houses.

1 Kuli, Culi, or Cooley is an estate adjoining Bishopscourt, and indeed in the form Culi seems to have been the name of Bishopscourt itself, or the estate that is now the demesne land attached to Bishopscourt.

|

|

||

|

|

||

|

Any comments, errors or omissions gratefully received The Editor |

||