Tower of Refuge, Douglas

[From Isle of Man by John Quine, 1911]

There has been a great decline and decay in the matter of industries on the island during the nineteenth century. The home industries once carried on in farm house and cottage, in the carding or spinning of flax and wool, and the weaving of linen, flannel, and home spun cloth have quite disappeared. The spinning-wheel is no longer found, except as an ornament in the drawing rooms of the wealthy; and even the knitting of stockings is no longer a cottage industry. But there are still a few woollen mills that once made flannel and cloth for the farmer from his own wool, and now continue to manu facture these fabrics for drapers in the towns.

When the herring fishery flourished, nets were made by hand in the cottages and later in small net factories in Peel and Port St Mary, but now these factories are closed, with one or two struggling exceptions. The country weaver with a loom or two in his cottage, once found in every district, has entirely disappeared. The country blacksmith and the country joiner have also to a very considerable extent vanished. Boat-building and ship-building which were active industries at Ramsey, Douglas, Peel, and Port St Mary half a century ago, are either completely extinct, as at Ramsey where vessels of large tonnage were built, and at Douglas where coasting schooners might always be seen on the stocks; or else greatly decayed industries as at Peel and Port St Mary, where schooners, sloops, and herring luggers once found employment for a considerable number of ship-carpenters, block-makers, sail-makers, and rope-makers. At the latter towns a few luggers are still built; but with this exception, and the building of pleasure-boats for the summer visiting season, this industry of immemorial antiquity in Man may be said to have ceased to exist. In the years 1898-1907 the average number of vessels built annually was seven, with an average tonnage of 17 tons.

Fifty years ago a disused cheese-press might be seen at almost every Manx farm, except where the press in a rare instance might be still in use. Now one may search in vain for an example to place in the local museum.

In 1511 licences were issued to 176 persons on the island to brew beer. Later the breweries were at various local centres, in the rural districts as well as in the towns, e.g. Ballaugh, Kirk Michael, Laxey, and in the neighbour hood of Port St Mary. There are now three breweries in Douglas, one at Castletown, and none elsewhere on the island.

The sea carrying-trade, in which till a quarter of a century ago a considerable fleet of Manx schooners and sloops were engaged, is now entirely carried on by steel built steam coasters. From 1898 to 190ß the number of sailing-vessels registered as belonging to the Isle of Man declined from 81 to 51, the tonnage from 9512 to 7707

Tower of Refuge, Douglas

With the decay of the sea carrying trade by sail has declined the subsidiary industry of rope-making, once active in Douglas, Castletown, and Peel. There existed a sail-cloth factory at Tromode near Douglas, in high repute for the quality of canvas supplied and exported for the largest class of sailing ships ; but with steam steadily ousting sail, the factory has recently been closed.' It 'may be said that the only industries surviving on the island are agriculture, mining, fishing, and catering for the half-million visitors who now make the Isle of Man their summer-holiday resort. Upon this last industry the agriculture of the island greatly depends for its fairly prosperous condition ; and to some considerable degree the fisheries also depend on it for a market.

There is a large demand for fresh milk, poultry, eggs, meat, and more especially lamb. There is also a good market for fodder for horses engaged in the excursion traffic which goes on during the summer ; and though many horses are imported, a great many are bred on the island.

The mining industry will be referred to later. The salt mine, recently opened at the Point of Ayre, has produced 11,129 tons of salt during the four years (1903-6) from the refinery at Ramsey. About 6000 tons of clay, 9000 granite, 9000 limestone, 2000 sandstone, and 16,000 tons of slate have also been registered as annually mined on the island.

The fishing industry consists first of the herring fishery, centred at Peel and Port St Mary. During the spring the boats fish on the south and south-west coasts of Ireland for mackerel, and return to the Irish Sea for the herring fishery from June to September. The number of boats engaged is much less than a quarter of a century ago. At the present time there is a steady decline in this industry. In 1898 the number of boats registered for the island was 341/0, with aggregate crews of men and boys, 1892. In 1907 the number was 237 boats, with crews numbering 1016. In the latter year there was also a slight decline in the average tonnage of the boats, viz. from 17 to 16 tons.

In addition to the boats engaged in the mackerel and herring fishing, a few boats are employed in trawling off the east coast of the island, where a considerable quantity of cod are taken in the spring. The herring are taken off the western coast, particularly between the Calf of Man and the Irish coast during June, July, and August, and off Douglas in September. There are also considerable quantities of turbot, plaice, sole, and other flat-fish, skate, and conger, taken by the trawl and by line. Mackerel fishing is a favourite summer sport off Douglas, and off Peel many sea-bream are caught.

Around the southern and eastern shores a number of fishermen make a living by lobster and crab fishing, the catch being generally despatched by daily steamer from Douglas to the Liverpool market.

Lime-burning is an industry carried on only at two kilns, at Ballahott and Billown, in the neighbourhood of Castletown. Formerly there were large kilns at Scarlett and at Port St Mary; but lime as a fertiliser has in late years been less in use than formerly.

At Kirk Michael and at Peel some oak-carving is done, chiefly of church furniture, but it can hardly be called a local industry in the sense of affording employ ment to a considerable number of people.

Garwick Beach and Glen

There are no coal measures known to exist under neath the Isle of Man. All the coal used is imported from the ports of Cumberland and Lancashire. In boring for salt at the Point of Ayre, secondary beds, supposed to be a continuation of those of the West Cumberland coal-field, have been pierced; but they have not as yet been tested sufficiently deep to decide whether there are coal seams.

Peat was formerly dug in the moorlands and curragh turbaries, and was the fuel of the island. The chief northern turbaries were west of Snaefell on the north slope of Pen-y-phot (Pen-y-phot = mountain of turf), and in the curraghs of Ballaugh and Lezayre. The chief southern turbary was on the east side of South Barule near Foxdale. There were also many lesser turbaries in upland hollows along the slopes of the mountain range. Very little peat is now dug.

The Manx slates have no true cleavage, as in the case of the Welsh beds ; consequently, though quarries have been opened and extensively worked on South Barule, in Glen Rushen, Glen Moar and elsewhere, they have produced no true roofing slate. For building purposes the stone used throughout the greatest part of the island is slate rubble ; in the south, limestone ; and around Peel, red sandstone.

Lime for agricultural and general purposes is obtained from the southern parishes. The stone was formerly brought round by sea to the northern parishes, and burnt by the farmer in his own kiln with brush fuel or peat. Later, kilns were erected at Ballahott, Billown, and Scarlett near Castletown ; at Port St Mary ; and at Derbyhaven. In recent years the use of lime as a fertiliser has become more expensive, and lime-burning is confined to the kilns at Ballahott and Billown.

On the Limestone formation near Ballasalla small deposits of umber, an earth containing oxide of iron, were formerly found in sufficient quantity to repay being prepared for paint, but the deposits have been exhausted, and the umber-works abandoned.

Brick-clay is found near Peel, and in Jurby and Kirk Onchan, but brick-making has proved unremune rative in competition with imported brick. In the parishes of Jurby, Kirk Andreas, and Kirk Bride marl was formerly dug in large quantities, and used as a fertiliser for wheat and other crops. Nearly every farm in those parishes had its marl-pit. The decline in the price of wheat has led to marl being no longer employed, but some idea of the extent of its use may be gathered from the size of the pits whence it was dug.

Iron was formerly mined at Maughold Head, but about 50 years ago the workings proved unremunerative and were abandoned.

The minerals in which the island is really rich are lead, zinc, copper, and silver-the latter being found in the lead ore and separated in the process of smelting. The principal mines are those of Laxey and Foxdale, but there were considerable lead mines at the following places (a) in the neighbourhood of Laxey, viz. the Corony in Kirk Maughold, Snaefell and Glenroy in Kirk Lonan, and East Baldwin in Kirk Onchan ; (b) in the neighbour hood of Foxdale, viz. Glen Rushen in Kirk Patrick, the Airey in Kirk Malew, Cornelly in Kirk German, and Glen Darragh in Kirk Marown ; and (c) in Kirk Christ Rushen at the southern end of the mountain range, viz. at Bradda, Glen Chass, Ballacorkish, and Balla sherlogue. In addition to these workings, carried on successfully for considerable periods, there was a small mine in Kirk Michael ; and there is scarcely a glen in any part of the island where there may not be found "levels" driven into the hill-side, on the line of surface indications of lead ore. There are also the remains of an old working on the Calf of Man.

Maughold Village

In the neighbourhood of Port Erin, at Bradda Head, there are very old workings, in which quick-lime was used as a slow explosive. Some of these workings are narrow and tortuous, showing that the old miners took out only the material in the vein ; and an impression existed among Manx miners that the men who had worked in these old workings must have been "very little men."

From extant documents it is known that lead was obtained from the Isle of Man in the thirteenth century for the roofing of the castles built by Edward I in Wales and the roofing of Cruggleton Castle in Galloway about the same period.

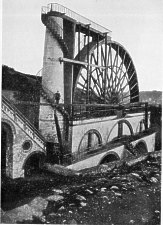

Laxey Wheel

The mines at Laxey go down to a depth of nearly 2000 feet, a depth below the surface as great as the height of Snaefell above it. The workings are under the Laxey Valley, in breadth about half a mile, and in length about four miles.

Recent borings at the Point of Ayre have resulted in the tapping of springs of salt-brine, which is now carried in pipes to Ramsey, and there evaporated and prepared for export.

The quantities of ore produced on the island for the ten years ending with î906, are as follows : lead, 36,445 tons; zinc, 20,654 tons; copper, 307 tons. The quantities of metal obtained from the ores were respectively 26,762, 8182, and 38 tons; and 578,827 oz. of silver, obtained from the lead. The average annual value of the metals obtained from these ores was :-lead, £38,330 ; zinc, £17,778brief, the annual value of metals derived from the existing mines on the island is £63,000. In addition to this the amount of salt shipped in the four years ending with 1906 was 11,129 tons, valued at £7174 at the works.

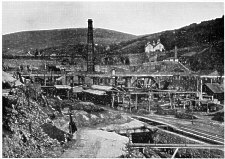

Lead Washing-floors, Laxey Mine

Half a century ago the mining activities on the island were very much greater than at the present day, when only the two principal mines of Laxey and Foxdale are in operation, and the number of men employed very much less than in more prosperous times. The decay of this industry is mainly due to the diminished price of lead.

Since the decay of the Manx mines there has been an extensive emigration of Manx miners to the gold-fields of South Africa and Australia and to various parts of the United States.

Such minerals as building sand, granite for road-metal, and limestone for monumental work, are found in various localities. The black marble of Poolvash was formerly in request for tombstones, and steps of this marble were in the seventeenth century used in St Paul's Cathedral : but the quarries are now only occasionally worked. Granite is quarried at the Dhoon, and is gradually coming into use over the island. The old raised beaches at St john's, at Douglas, and at Ramsey supply a very fine quality of sand for the purpose of the local builder. In conclusion may be mentioned bog-oak, found in the northern curraghs and occasionally used for cabinet work. The crozier of the Bishop of Sodor and Man is a fine example of carving and silver-work ; the bog-oak of which it is made being of a texture closely resembling that of ebony.

The herring fishery of the island was at one time a far more important industry than it is now. The two Manx towns of Peel and Port St Mary were formerly dependent on this fishery and on the subsidiary industries, such as boat-building and net-making, associated with it. Both these towns are still to some degree engaged in the fishing and dependent on it, but they have come to be to a far greater degree dependent on their attractions as holiday resorts during the summer season.

One cause of this is that the fish do not return as in former times to their haunts in the Irish Sea. The Irish Sea was formerly the resort of immense shoals of herring, coming in. their annual migration from the outer seas to spawn in these enclosed waters. They arrived in June and departed in September, and were in prime season at the beginning of August. In the thirteenth century Manx statutes strictly define the payments of tithe on fish. At that time each parish had its boats sailing from its own creeks; and probably the main part of the fish caught was salted down for winter use.

In the reign of James I an enquiry was held touching the then decay of the herring fishery, and "ancient men" gave evidence that in their youth they had drifted for herring in the north of England, viz. towards the Solway. But in later times the main haunt of the herring was off the Calf of Man towards the Irish coast in the early part of the season, and off Douglas and Derbyhaven in September.

In the enquiry mentioned above the boats were then "Scoutes of 4 tunns," and every tenant within the Isle was obliged to have "8 fathoms of nets, with corks and buoys, containing 3 deepings of 9 score meshes upon the rope." The nets were made in the farmers' and fisher men's homes during the winter, and this continued till about 1850, when net factories were established in Peel, and later in Port St Mary. There was in the sixteenth, seventeenth, and eighteenth centuries a considerable export trade of salted herrings from Peel to Spain and Portugal, and even to Italy.

Luggers at anchor, Port St Mary Bay

In the early and middle decades of the nineteenth century the Manx herring fishery reached its greatest importance; and its decline may definitely be said to date from thirty years ago. Peel had 400 fine luggers each with a crew of seven hands, and Port St Mary about 250 luggers. There were red-herring houses in Peel and in Douglas. The winter consumption of salted herrings on the island was larger than now: it was then a most important staple of diet. The boats fished not only from their home ports, but according to the season followed the shoals of fish to Stornoway, the Shetlands, the cast coast of England, and southwards to the stations of Howth and Arklow in Ireland.

With the partial failure of some of these fishings the Manx boats began the new industry of mackerel fishing on the south coast of Ireland, with Kinsale as centre ; and later worked the industry westwards as far as the Shannon, with Berehaven, Valentia, and Fenit as centres.

The cause of the decline of this great insular activity is to be found not only in the comparative failure of the herring shoals in the Irish Sea, but in other concurrent factors. The agricultural system, when much labour was required on the land, supported a class of people who were partly agricultural, partly seafaring. The labourer's cottage was the nursery of the fisherman. There was a race of fishermen, which may be said no longer to exist. The fishery is no longer lucrative, and this combined with other causes has driven the fishermen to other occupations.

The non-return of the shoals of herrings, whatever be its cause, does not stand alone. Haddock were formerly caught in great numbers off Peel, but have now practically disappeared. Sea-bream, locally called carp, were also very plentiful off Peel in the herring season : they are still taken, but in much less numbers. The hake and other fish that fed on the herrings have also become much less common.

The market for Manx herrings was in the first instance Liverpool. The fish-buying sloops and steamers met the fleet at sea, or in Peel, and could land their cargo in Liverpool the same afternoon. There are now no vessels, either sloop or steamer, in this trade. A large quantity of herrings are now "kippered," viz. split and dried, and sold almost fresh. Herrings are salted for export in Douglas: this industry being an attempt at a revival of a trade which was once profitably carried on when Peel sloops could secure a home freight from Spain and Portugal, and when salted fish was more in demand as a staple of diet.

Port Erin Bay

In Danish times mention is made only of St Patrick's Isle or Peel, Ramsey, and Ronaldsway or Derbyhaven as landing-places in the historical incidents of that period. Godred Crovan landed at Ramsey; as did later the hostile expeditions of the Irish Danes against Olaf I, and of Somerled of the Isles against Godred 11, and King Robert Bruce, in 13j3. Magnus Barefoot landed at St Patrick's Isle ; Godred 11 died there; and there, in 1228, were wintering the ships of Olaf II and of the Chiefs of Man when Reginald the King's brother burnt them in a hostile raid. Ronaldsway is mentioned oftener when we come to the thirteenth century, viz. as the landing-place of Reginald, of Scottish expeditions, and of a marauding expedition of the Irish de Mandevilles.

By 1511 however, after a century of Stanley rule, Castletown and Douglas are found to be by far the most important places on the island: Castletown had then 150 houses, and probably a population of 6o0, exclusive of the Castle garrison. Over 60 of the houses had gardens; there were 12 wawhouses, 14 cellars (or warehouses), two mills, and a "hawkhouse." Out of 67 surnames in the town 44 were English, and definitely Lancashire names; the remaining 23 Manx. Douglas had 80 houses, which were mainly cottages, only two with gardens; there was one brewhouse, but no " cellar " (or warehouse). Of 43 surnames in the town, 18 were English, and 25 Manx. Peel was a place of 19 houses, say with 100 inhabitants; and of 16 surnames, 12 are English and four Manx. At Ramsey there was no nucleus of population, though there were 25 houses in the abbey village of Ballasalla.

In the sixteenth century trade increased considerably, and in the seventeenth century both Douglas and Ramsey had the protection of forts. Both these towns and ports owed their expansion at the end of the seventeenth and during the greater part of the eighteenth century to the smuggling trade. The smuggling trade was to Douglas what the slave trade became later to Liverpool : the stones of old Douglas were laid with lime slaked with contraband liquors. The population of Douglas increased as follows. In 1726, 810; 1757, 1814; 1784, 2850; 1821, 6054; 1861, 12,389, 1901, 19,223; and in 1911, 21,101. The population of Castletown increased from 785 in the year 1726 to 2531 in the year 1851 ; and from that time shows a decline in each decade, sinking to 1965 in 1901 and 1817 in 1911. Peel, from 475 in 1726, reached its maximum population of 3829 in 1881,-the period when the herring fishery had begun to decay-and has since steadily declined to 2590. Ramsey, from 460 in 1726, reached a maximum of 4866 in 1 891, and has shown a decrease to 4216 in the last census of 1911.

Douglas, from Douglas Head

The Isle of Man Steam Packet Company, centred at Douglas, was established in 1820 mainly for a regular service between Douglas and Liverpool. Other local efforts have attempted to maintain steamers between Castle town and Liverpool, and Ramsey and Liverpool, but have ended in failure. The Douglas service has developed with the industrial expansion of the north of England manu facturing industries, and the type of the vessels has been of the highest standard of cross-channel boats. The number of vessels in this fleet remains about 12. The latest added, to replace obsolete boats, are of the turbine class, carrying 2500 and 2000 passengers respectively, with a speed of 22 knots. In the winter a daily service is maintained both ways for passengers, mails, and cargo. In the summer the number of sailings is much increased, according to the increase in passenger traffic. The Company maintains a bi-weekly service between Ramsey and Liverpool in winter, a weekly service between Douglas and Glasgow, and a fortnightly service between Ramsey and Whitehaven for the shipment of agricultural produce and stock. In the summer there is a daily service between Douglas and Fleetwood, and the Clyde service is maintained thrice weekly between Douglas and Ardrossan. There is also a service to Dublin, and to Llandudno in Wales, and between Peel and Belfast.

The Midland Railway have also established a daily service between Heysham (near Lancaster) and Douglas during the summer months; and a Blackpool steamer maintains a service between that watering-place and Douglas.

Douglas Pier, Isle of Man S. P. Co.'s Steamers

During the ten years from 1898 to 1907 the number of passengers landed on the island increased from 36o,177 to 528,367 : the tendency being towards a steady increase in the number, subject to fluctuations due to the depression or prosperity of trade in the north of England.

In addition to these steamers engaged in passenger traffic, there are on an average from year to year about a dozen smaller steamers registered as belonging to the island, engaged mainly in carrying coals and other cargo to Douglas, and in the shipment of lead ore from Laxey and Ramsey.

Of other tonnage there is registered 7707 tons, dis tributed over 51 sailing vessels; but ten years ago there were 81 vessels of 9512 aggregate tonnage. Timber is imported in Norwegian vessels, mainly to Douglas, though an occasional brig discharges at Ramsey and at Peel.

Ramsey Harbour

For passenger traffic there are magnificent low-water landing piers at Douglas and Ramsey. For cargo, the ports have tidal harbours, where vessels may be neaped up to about 300 tons burden, and in Douglas harbour, up to 500 tons. In connection with the erection of its low water piers and breakwaters has been contracted the principal part of the Insular Government Debt, which amounts at present to £230,000.

We have already glanced at the outlines of the early history of the Isle of Man, and may now pass to the events of more modern times.

About 1076, Godred Crovan, who fought under Harold of Norway against Harold of England at Stamford Bridge in 1066, defeated Sitric son of Fingal at Sky Hill near Ramsey and conquered the island. His dynasty held the island-except for a brief period about 1095 when it was seized by Magnus Barefoot of Norway-till 1266; though, it is supposed, his last descendant was not ousted till the Battle of Cross Ivar, near Ronaldsway, in 1275. With this battle ended the independence of the island, and Man came under Scottish rule. Edward I seized Man as part of the realm of Scotland. Robert Bruce recovered it in 1313, but in 1332 it finally became part of the realm of England.

Edward III granted the island to Montacute, Earl of Salisbury, whose son, the second Earl, sold it to Sir William le Scroope. On his fall and execution by Henry IV, the Isle of Man was granted to Percy, Earl of Northumberland; and on the defection of Percy from the King's cause, in 141/06, it was granted to Sir John Stanley, whose descendants were Kings of Man till 1736, though the title of "King" was dropped and that of "Lord" retained by Thomas Stanley, second Earl of Derby, in the reign of Henry VII.

The island adopted the Reformation in the sixteenth century, with little change in religious usage. The same clergy continued to occupy their livings under the new system, but the property of the monastic houses was, as in England, seized by the Crown. There is evidence of con siderable sea trade having existed at this period between the island and England, and even a trade with France and Portugal. But the internal history was mainly a struggle of the Manx people with the Earls of Derby over the title and tenure of their estates.

In the seventeenth century James Stanley, seventh Earl of Derby, held the island for seven years against the Parliament. On his death, in 1651, the island declared for the Parliament. In that century, and more especially in the eighteenth century, Man was a great smuggling centre. Through failure of heirs of the Stanley line, the island passed in 1736 to the then Duke of Athol, a collateral heir, and he encouraged the activities of the contraband trade, from which indirectly he derived his revenue. In 1765 the Athols sold the sovereignty of the island to the English Crown, and, in 1827, all other rights and privileges.

By the middle of the nineteenth century the Isle of Man had begun to be visited in considerable numbers by summer-holiday visitors. It had long been a place of residence for people attracted by the reasonable cost of living, a steam packet service having been established between Douglas and Liverpool as long ago as the year 1820. With the development of the industrial activities of Lancashire the island became more and more a holiday resort; and by the end of the nineteenth century the annual number of visitors had exceeded 400,000. The actual number of persons that landed on the island in 1907 was 528,367

|

|

||

|

|

||

|

Any comments, errors or omissions gratefully received The Editor |

||