[From The Studio vol 32 No 136 July 1904]

BY

|

|

|

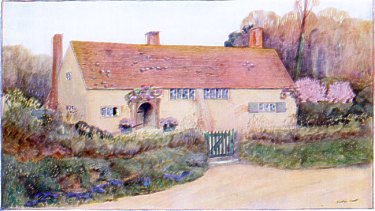

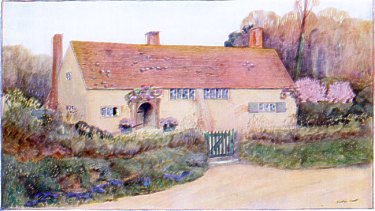

A Country Cottage

|

|

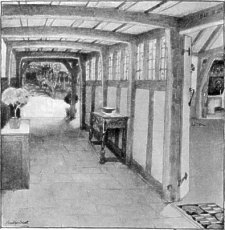

THE sketches which accompany this article show the plans and some aspects of a small summer, dwelling recently designed for an artist. On opening the front door-a door roughly constructed of oaken planks and fitted with homely metal work-one enters a passage wide and low, where the grey-brown of timber, which, roughly finished by the adze, seems to still retain some hint of its woodland home, and to bear evidence to human handicraft, is supplemented by cool spaces of innocent whitewash and by the subtle variation of grey tone in its stone-flagged floor. From the cool shade of this low passage, one looks beyond to the sunny, open space of a garden courtyard, and beyond this through the vista of the pergola bordered with flowers and roofed with leafage. Through the leaded glazing of the screen which forms one side of this passage, one obtains a hint of the hall, which relies for its effect as the passage does, on mere building. The modern tradition of house building, which ends by making a room or a passage a rectangular box lined with smooth plastered surfaces, and which then proceeds to decorate these surfaces with superficial materials covered ;with patterns, is here set aside for the realities of the structure itself.

View from From Entrance

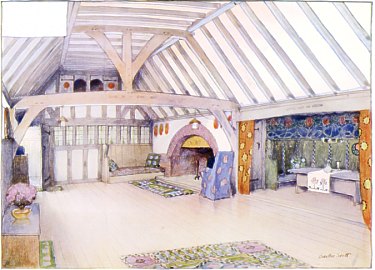

In the hall or house place, which forms the principal apartment of this country dwelling, and which indeed almost constitutes the house, the grey-brown of timber and the whitewashed wall spaces seem to demand little aid from superficial decoration, and this is confined to the dining recess, mainly as an expedient to add to the richness and depth of the shade under the beam which divides this recess from the hall itself. The special uses and advantages of this dining recess as a substitute for a separate dining room have already been set forth in THE STUDIO. In the winter time perhaps its greatest advantage consists in its tendency to simplify the heating problem in the average house. Households may be classified by the number of fires which are normally used. In the labourer's cottage one finds a one-fire household, and the general use of the kitchen in preference to the parlour results from the reluctance to maintain any other fire but that one used in cooking. In the average small household one finds a similar reluctance to keep up more than one sitting-room fireplace, and so it is often the dining-room which is constantly used as a general sitting-room. For such a household it seems reasonable that the partial incorporation of the diningroom in the general house place should be adopted, so that during meals the family may share in the warmth and spaciousness of the hall instead of being confined within a separated cell, which it hardly seems worth while to warm merely for its intermittent uses.

Apart from such considerations, it may be noted that in a public restaurant it is always those seats against the wall which are chiefly occupied. In the early days of civilisation this position for dining was chosen chiefly because of the excellent posture for defence thus secured and although it is now happily no longer necessary to thus protect oneself from a treacherous foe, the instinct to do so may survive and give an added sense of comfort and security to a seat against a wall.

A Country Cottage - The Hall

To realise the best effect of this arrangement of the dining table, one must imagine the hall itself somewhat dimly lit, so that the timbers of its open roof lose themselves in vague shadows. On the great open hearth a fire of wood sheds a ruddy glow over the room, while the dining recess itself is screened by curtains, broadly decorated with applique embroidery, and then when the dinner is served and the curtains drawn back the hidden brightness of the table and its appointments is disclosed, and as in the stalls of some ancient refectory the family take their appointed places against the deep-toned background of the seats. It will be noted that the service route is from the pantry across the garden room. In winter time this garden room would be enclosed with glazed shutters and form a miniature winter garden, but in summer time it is the garden room itself which would be chiefly used for meals, and for this purpose the service is specially arranged.

The garden room in these days, when the advantages of a life spent, as far as possible, in the open air are increasingly realised, becomes an essential feature in the country house, especially in one designed mainly for summer use. On summer mornings it is here the family would meet for breakfast, and while enjoying the advantages of the open air they would be sheltered from a sudden shower.

One of the disadvantages, from an economical point, of the house which consists of one storey only, is, that much space is often wasted in the roof, especially if this is high pitched. In the plan illustrated it has been arranged that the roof space should be fully developed by making the bedrooms partly on the ground floor and partly as attics in the roof, while in the hall the inclusion of the roofing in the room helps to give a character which it is difficult to obtain in a room with a flat ceiling. It will be noted that the passage which crosses the house from front door to garden room cuts off and isolates the kitchen premises from the rest of the house. Over these a small staircase gives access to the servants' bedroom over the kitchen and to a small gallery over the passage itself. At the opposite end of the house, on the ground floor, is the principal bedroom with bathroom adjoining, and a second little stair gives access to two attic bedrooms over these. An enlargement of the plan where more bedrooms were required would principally consist of an extension of this wing, and if the ground floor were developed as a bed-sitting room with the bed in a recess, it might open with a wide doorway from the hall and thus add to the general floor space.

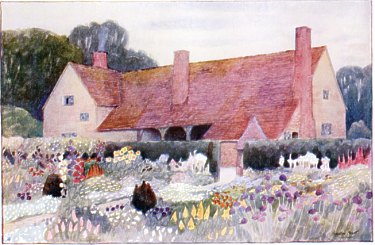

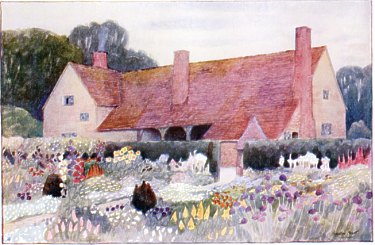

General Garden Plan

Having thus considered briefly the plan of the house, it will next be necessary to describe the principal features of the garden, for in a summer dwelling the garden is perhaps even more important than the house itself, and its apartments and leafy corridors are but an outdoor extension of the house plan, so that house and garden are each a part of a whole comprehensive scheme. The plan shown for the garden is submitted mainly as an example of certain principles of design in laying out a plot of about half an acre in extent. It is not suggested as a suitable scheme for any site, for each will demand its special treatment. And in such treatment much will depend on the due recognition of local features and conditions. If, for instance, one could include within the boundary of such a small domain some woodland copse where in the spring blue-bells, primroses, and violets grew in nature's way, it would be well before destroying such natural loveliness to seriously consider whether it would be possible to rival it with garden flowers, however skilfully disposed. It were better to take a hint from nature, and instead of frustrating her efforts to fall in with her ideas and strive by the art of man to raise them, as it were, to the "nth" power. The plan I have shown must, therefore, be accepted with certain reservations. One of the most important principles which it illustrates is the importance of vistas in the effect of a garden-vistas arranged with definite terminal effects. Of these one of the most important has already been noted, that from the front door, looking down the passage and pergola beyond -a vista which helps to emphasise the essential unity of house and garden-while a reference to the plan will show many others which may be noted if one takes an imaginary stroll round the garden. From the front gate a broad paved path leads to the front entrance, intersected by a narrow path at right angles to it. The roadside part of the garden is here formed by this path, terminated at each extremity by a garden ornament or tree, surrounded by a plantation of semicircular form.

Taking the path to the right, the first important vista is disclosed on reaching the point where another garden path meets it at right angles. Here one looks through a walk bordered by shrubs, and beyond into the rose-garden, orchard, and watergarden. Proceeding down this path, a cross vista occurs as soon as one reaches the sundial in the centre of the rose-garden. Passing on into the orchard, where the paths consist of stone flags or bricks laid in the grass, bordered by drifts of daffodils, the next cross vista occurs in looking towards the circular herb-garden across the pergola.

Passing into the water-garden, with its central stream and paved margins, and turning to the left, an important vista reveals itself on reaching the opposite extremity, where one looks through the herb-garden, kitchen-garden, and well-court; and walking up this path back towards the house, one passes again the two cross vistas. Such a principle of arrangement is necessarily more interesting than the mere disposition of winding walks, which never fulfil the promise they seem to convey of some vision of the beyond. The defect of the formal treatment often lies in a certain barrenness, a lack of mystery, and those surprises and dramatic effects of light and shade which are such essential attributes of the garden. Open flower gardens are best approached through dim and shady alleys, and everywhere broad and open sunlit spaces should be contrasted with the shade of pergolas and embowered paths. In passing through these enclosed ways one loses all conception of the garden scheme till at the intersection of a path one suddenly perceives through vistas of roses and orchard - trees some distant garden ornament, or, perhaps, a seat or summer-house; and so one becomes conscious of a scheme ordered and arranged to secure definite and well-considered effects. As in a dramatic entertainment, apartments of the garden, full of tragic shade, are followed by open spaces where flowers laugh in the sun; and by such devices the art of man arranges natural forms to appeal in the strongest way to the human consciousness.

In such arrangements one of the most important considerations is the proper subordination of certain parts as backgrounds. The modern gardener is apt to look upon such features as yew hedges in the garden as mere archaic affectations, and he points to many modern flowering shrubs as being more preferable than the sombre yew. As a "matter of fact, the yew maintains its place chiefly on account of its unequalled background qualities. Roses and lilies seen in a setting of flowering shrubs are still roses and lilies, to be sure, but they have lost much of the beauty of their effect they might have displayed if relieved against the dusky yew, which enters into no competition with their brightness. And so, to a great extent, the more permanent framework of the garden may be regarded as a sort of stage and setting for the passing pageant of the flowers.

It will be noted that the garden scheme under consideration includes no lawn or mown grass, and this omission is chiefly due to the desire to obtain in a cottage not constantly occupied a garden which will not demand that constant attention which the ,will of mown grass entails. The orchard which replaces it will yield the beauty of its blossom and its kindly fruits with but small exactions. The paved paths will afford little scope for the growth of weeds, and the garden as a whole when once established will not demand much outlay in maintenance.

In the treatment of the exterior of the house I have tried to achieve a simplicity of form which would convey that air of repose which belongs as a matter of course to old farmhouses and cottages, but which is not so apparent in the modern country dwelling which "pricks a cockney ear" above the tree-tops. The modern landlord, who rejoices to disfigure the landscape with " sanitary " cottages, apparently has a rooted conviction that the picturesque qualities which mark the old country buildings are necessarily incompatible with sanitary and economic conditions. The art factor in much modern building is indeed an expensive as well as an undesirable addition, but actual simplicity of proportion and treatment is not necessarily a matter of extra cost. It is well that we should build for health, and it is true that many of the older buildings are lacking in this respect. It is not well that in building for health merely we should forget those nobler attributes which the ancient builders achieved, and which may find expression in the humblest cottage.

|

|

||

|

|

||

|

Any comments, errors or omissions gratefully received

The Editor © F.Coakley , 2011 |

||