Photograph of the author at the time of his imprisonment.i

[p. 9 Preface to Die Männerinsel ]

Photograph of the author at the time of his imprisonment.i

The dedication of these personal records, which now, after twenty-five years, are losing their purely private character, to my father, obligates me to fill in a gap which has arisen in my records.

The reason was that I came across my father in the Douglas Camp as a fellow-prisoner on 15th November 1915. But the circumstances dictated that during our joint stay there was to be no contact between relatives, and I also omitted any mention regarding this in my personal records. —

When I was still living at Mrs v. L.'s residence in London, one day I was reading the debates in Parliament and did not believe my eyes when in that session matters concerned the life and death of my father, whom a court martial was about to condemn to execution by firing-squad in the Tower of London.

My father, the son of an US citizen in Germany, had sought German naturalisation in order to enter the Imperial German Navy. He had, already as a midshipman, at the end of the 1870s, joined Prince Henry, the brother of the later Emperor William II, in a voyage around the world on the Adalbert. At the beginning of the current century he was commandant of His Imperial Majesty's Ship Möweiii in the South Seas, where he was able to suppress several rebellions instigated by the English on Samoa. He had been compelled by a severe tropical disease to leave the Navy. — Despite this, when the World War broke out, my father reported voluntarily for the Secret Intelligence Service, and was given the task of determining the strength of the British Grand Fleet. He also ascertained [p. 10] this strength on the Orkney Islands (Rosyth);iv however, in Inverness he was betrayed and arrested.

It was around this time that my visit in London from the men of Scotland Yard also took place; they had probably sensed some connections from my name, and wanted to investigate these. Since the details on my passport that was issued by the police in Hastings at the beginning of the War gave me (falsely) a much more juvenile age, and since in addition I did not dare to give a family relationship, I even then escaped my fate, and Mrs. v. L. also held back from any making any dangerous remark during the interrogation. If in the meantime a more thoroughgoing house-search had also brought my diary, which I kept well hidden, to light, it would have served as incriminating evidence against me. My remarks concerning my father I destroyed at that time.

When so unexpectedly, and to my secret joy, I came across my father in person, we finished up with the above-mentioned agreement. It was the best for both parties, because repeated enquiries took place, and my father was twice taken off to London, where on each occasion his life hung by a thread. Finally it was the efforts of America, which was approached very widely up to its final entry into the War, which gave my father's fate the saving direction. In the summer of 1918 he was released to Germany, and promoted there to the high rank of captain in the Imperial German Navy.

The manuscript as presented here also contains, through its time-bound nature, superseded views and impressions of the moment. But in the interests of immediacy I have neither 'retouched' them in line with altered points of view, nor subjected the truth to an emendation, as one finds in many 'memoirs' diminished by this. I didn't do this because even when I was noting them down, I paid little regard to possible unauthorised readers, who could easily use anything against me, [p. 11] because I wanted to write a strenuously factual report, 'sine ira et studio',v about the country in whose power I was, even if the report was intended only for me. Not until many years after the War was I successful in placing my hands under circumstances of considerable difficulty once more on the often scattered pages, some of them even believed lost. I had not considered publishing them, and did not allow myself any change of mind until the present day, which once more causes the past to glare up harshly.

Prague, March 1940.

i The photograph as presented in the book is very probably that of a fifteen- or sixteen-year-old. However, that would have been in 1904-5, when Dunbar-Kalckreuth was still in school in Germany. There is another image of him, a painting in the Manx Museum (Douglas, IoM), which was done of him in Knockaloe in November 1915, and shows him at the age of 26 (his real, and not imagined, age). It is mention on page 178 of the original book, and can be found on www.imuseum.im under "Dunbar":

Manx Museum PG-8655-1702 - with permission

(the barely legible signature near left shoulder is Franz Kampf Douglas 14.IX.16)

ii Frederic Lewis Dunbar-(von) Kalckreuth, born 20 December 1888 (Wilhelmshaven), died 15 August 1953 (Stukenbrock, Westphalia). Die Männerinsel was published on 4 May 1940. The German invasion of the Low Countries began on 10 May 1940. The typeface of the original is Old-German Walbaum-Fraktur.

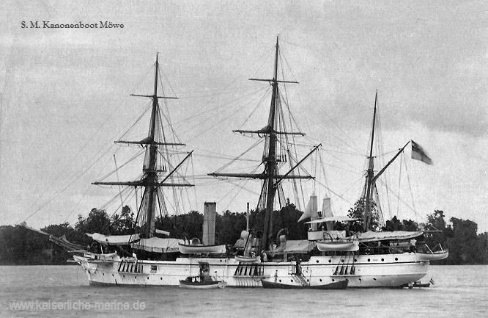

iii Möwe '—seagull'. Möwe (keel laid down in 1879) was a gunboat of the Imperial German Navy in the German West Africa Squadron. In 1888/9 she was deployed to East Africa, and then in 1895 to German New Guinea (Papua and Samoa). She was decommissioned in 1905. Her story, and in part that of 'Captain D(unbar)' was told by Johannes Wilda (German journalist and author) in Reise von S.M.S Möwe. Streifzüge in Südseekolonien und Ostasien,—Voyage of His Imperial Majesty's Ship Seagull. Expeditions in South-Seas colonies and East Asia' (Berlin: Allgemeiner Verein für Deutsche Litteratur; 2nd edition, 1903; old-German typeface). He relates on page 3 (English by G.N.): —I left the harbour of Hong Kong on board S.M.S. Möwe, a German special-purpose survey vessel, with the kindly-sponsored intention of carrying out a study journey to the Bismarck Archipelago. The Möwe was a timbered cruiser of only 845 tons displacement. The 'malicious world' called her an 'old crate'. However, we had previously been with her in Kowloon Dock, from which we emerged very spick and span indeed, so spick and span that every man on board was filled with pride at the little white ship on whose protruding bow our golden heraldic bird hung in all its splendour. The commander, Corvette-Captain D.[unbar], experienced old seaman that he was, had additionally ordered the graceful three-mast schooner to be further embellished by having its topmast re-rigged; and, without a word of flattery, to external eyes we looked just like an elegant pleasure-yacht.

s

s

S.M.S. Möwe, 1879-1905

iv Dunbar-Kalckreuth errs: Rosyth is not on or in Orkney; it was a naval dockyard of the Firth of Forth, at Rosyth, Fife, Scotland. Its construction began in 1909, and was not fully complete when the War broke out. Ships from there were intended to defend the east coast of Scotland against attack from Germany.

v Tacitus, Annals, 1.1: 'without fear or favour'.

|

|

||

|

|

||

| Any comments, errors or omissions gratefully received The

Editor HTML Transcription © F.Coakley , 2018 |

||