This page looks at the development of the Douglas camp.

Cunningham's Holiday Camp was requisitioned as a Civilian Alien Internment Camp - B. E. Sargeaunt (Government Secretary) states:

A deputation from the Civilian Internment Camps Committee, consisting of Sir William Byrne and Mr. Montefiore, came to the Isle of Man in September, 1914, to ascertain from the Manx Government whether accommodation could be provided in the Island for the immediate internment of alien enemies who had been arrested in London and elsewhere, and who were being temporarily interned in various buildings as a preliminary step. The Holiday Camp at Douglas, where young men from the mainland were accustomed to come and camp for their summer holidays, was at once thought of, and before long this Camp was in the hands of the Government. Barbed wire fences were speedily erected, gas and electric standard lamps were introduced for lighting the compounds at night, various guardrooms were built, and other alterations made. On the 22nd September, 1914, the first consignment of 200 prisoners arrived.

All Official Internee records were held by London - the originals being destroyed by enemy action during WW2 and a duplicate set destroyed, probably by accident, during the 1970s. A large collection of records, accounting to ¾ ton were it seemed still held by the IoM Government (probably by the Police); in 1955 when feeling they had no further use for them, they wished to destroy or transfer them - after some consulation with UK National records who did not want them, it seems the major part was destroyed, probably by dumping down a mine shaft as had been used in the 1920s and 30s. However some records still survive of which the admissions and discharge register of the Douglas Camp is one notable exception - now held at MNH Library Manx Museum as MS 09310. The single ledger holds two lists - one of names in alphabetic order and the second in numerical order. This numeric list is of ruled and printed columns spread across two pages :- General number, Nationality, Surname, Christian Names in full, Rank, from whence received, date on which received, personal effects, discharged etc, place to which transferred and remarks - probably originally intended as a a register for the Gaol. However the date of reception is left blank until camp numbers reach the high 3000s, usually just the place and date of transfer out of the camp are given. One feature however is that every transfer out is entered and if the internee is re-admitted (eg after a spell in prison) he is re-entered under a different camp number. There would appear to be no breaks in the sequence and thus the Douglas Camp number is based solely on date of admission. Another key survival is the daily log kept by Col Madoc who was seconded from his post as Chief Constable of Douglas to be Commandant of Douglas Camp.

These merged with other surviving records, have been entered into an Internee database online (www.imuseum.im). A sample of some 7.5% of the nearly 13000 names has been used to provide an initial examination of Internee numbers.

Douglas Camp allocated numbers go up to 5901 - however this does not mean the camp held 5900 - Sargeant states:

On the 24th October, 1914, there were in the Camp, which was, at that time, guarded by the Isle of Man Volunteers, 2,600 prisoners of war, which was the official establishment, but, in order to assist in relieving congestion in temporary places of internment in London and elsewhere, a temporary increase to 3,300 prisoners was authorized.

This is confirmed by the report of the Destitute Aliens Committee occasioned by the riot in the camp on 19th November 1914:

The Committee originally approved of this camp as suitable for the detention of 2,400.

The numbers were however, with the consent of the Committee, temporarily increased by some 900 owing to the necessity of providing accommodation at once for a larger number of interned aliens than the War Office could cope with.The Committee are of opinion that the numbers in this camp should be reduced at the earliest possible opportunity to at most 2,400, so as to put an end to the present overcrowding ...

Arrivals of these 3,000+ internees was by special boats into Douglas Harbour with disembarkation followed by a march to the camp in the early morning - which soon, it appears, became a popular 'entertainment' for Douglas resisdents - see under Arrivals.

Once Knockaloe was available there were large groups transferred from Douglas - inter-Camp transfers were common throughout the war, my estimate is that well over 60% of Douglas Camp Interneess were at sometime transferred to Knockaloe - in the early days as Knockaloe was being constructed several contingents were sent, with other significant transfers in late summer 1915 - in some cases a transfer to Knockaloe was an additional punishment for some infringement of camp regulations.

There were also a smaller number of transfers to Lancaster most of which would appear to be under 17, though Col Madoc was permitted to send a few 'trouble-makers' there as well. The daily log kept by Col Madoc gives much detail about these transfers - though his hand is very difficult to read in sections. Many of those sent to Lancaster landed back on the Island at Knockaloe when Lancaster camp was closed.

Most internees were not released until the early months of 1919 with large batches of internees going by early March 1919 - they were transferred to camps in the UK (e.g. Spalding, Ripon Alexandra Palace etc.) often indicated for repatriation. The last departures were to Knockaloe in early April 1919 so that the camp could return to its use as a holiday camp in the 1919 season where it was noted that demand for accomodation for July and August 1919 outstripped capacity. Many Knockaloe internees were not to be released or transferred until August or September 1919.

Sargeaunt in his description continues:

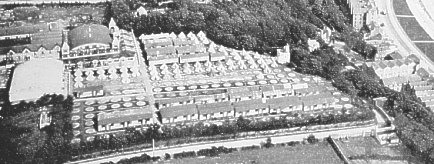

A postcard issued in 1919 showing the immediate post war state

The prisoners of war slept in tents and messed in a large permanent building. Later, the tents were superseded by huts, and the Camp was divided into three sections : (1) the Privilege Camp ; (2) the Jewish Camp ; (3) the Ordinary Camp . To qualify for the Privilege Camp, a prisoner had to pay a weekly subscription, which entitled him to better accommodation, better meals, and a prisoner servant. On food shortages arising in the country, the food of the prisoners in the Privilege Camp was rationed to the same amount as that for the ordinary prisoners, and the power of making purchases of food in the town, through the medium of the Order Office, was cancelled. The members of the Jewish Camp were provided with Kosher food and were given facilities for celebrating Jewish festivals.

There are some records in the admissions register of Jewish internees 'who refused Kosher' and were then transferred to Knockaloe.

Frederick Lewis Dunbar in his 1940 publication includes a sketch plan of the camp as he remembered it in 1915-1918:

Plan of Camp as found in Die Mannerisel

[Stacheldraht = barbedwire, Holztürme = watch towers, Wiese = meadow ground]

Victoria Road runs between the two sections of the camp which were joined by an underpass; Victoria Road Prison [Zuchthaus] is top lefthand. The upper camp holds the small Jewish section and the main camp with a mixture of huts[Baracken] similar to those of Knockaloe and bell tents [Zelte], the lower camp is the privilege camp consisting of tents and small cabins made from asbestos sheets. The Brush factory [Bursten Fabrik] is outside of the camp.

Sargeaunt however quickly skates over the serious outcome arising from a demonstration by many internees complaining about the poor quality of food:

On 19th November, 1914, five prisoners at Douglas Camp were shot by the guard. An inquest was held on the 20th and 27th November by the High-Bailiff of Douglas (the coroner for inquests) and a jury. The verdict was "that the five deaths were caused by justifiable measures forced upon the military authorities by the riotous behaviour of a large section of the "prisoners interned." Previous to this "riot," there had been some disaffection in the Camp for some little time.

The initial two months of Douglas Camp were ones of highly unsuitable accommodation and inexperienced management. Fyson comments that "due attention has not been paid to the less pleasant or creditable aspects of Manx history". The camp consisting mostly of tents, though a few small chalet-like buildings built using asbestos sheets had been erected, was intended for the short summer season and completely inadequate for a typical wet and windy Manx winter - the early part of the winter proved to be worse than usual and was one of the reasons the construction of Knockaloe was behind its promised schedule. The weather struck early with many tents washed out by the 2nd October and Col Madoc wanted huts to be considered. Joseph Cunningham still had control of the kitchens and provision of food although now to the War Office prescribed diet rather than the prewar tourist menu that had proved a major attraction for camp residents. Poor quality or rotten meat was being supplied as well as poor quality potatoes - this provoked many complaints from early October onwards. Madoc had already asked for the provision of huts and more guards than were available from the local IoM Volunteers - an extra 15 from the Loyal Manx Association were added and on 24th October 50 men and two officers of the National Reserves arrived from Liverpool. Even though Madoc had quelled the discontent over bad food and poor living accommodation the weather was still against him and though on the 9th November the construction of the necessary huts had begun with contractor labour augmented by internees, work stopped on the 18th when carpenters went on strike for more pay. The appearance of weevils in the meal on the 17th provoked a hunger strike on the 18th with the singing of patriotic German songs accompanied by the band that had up to then played at the main meal times - Madoc arrested one 'agitator' and stopped the walks, incoming and outgoing mail as well as the band at meal times. Thus the scene was set for the 19th November.

A visit by a Press Association representative took place on 28 November 9 days post the shootings - Knockaloe was also viewed - a small Parliamentary committe made brief visits to both camps in April 1915.

The significant change in the nature of internment post the sinking of the Lusitania on 7 May 1915 is discussed elsewhere but as Sargeaunt comments it also had an influence on those in the camp:

The Camp was visited in June 1915 and again visited in late 1915 by the Americans - their report gives a glowing picture of the by then two distinct camps - Dunbar gives another picture of life here, as does Schönfeldt.In the late autumn of 1914, in addition to the Isle of Man Volunteers, National Reservists (afterwards the Royal Defence Corps) were sent to the Island to guard the interned prisoners of war [sic] ; they also escorted them on their marches for exercise along the country roads. These marches of prisoners, in bodies of about 200 each, were allowed until 12th May, 1915, when they were stopped as a result of the prisoners having cheered in the streets on reading newspaper posters announcing the sinking by a German submarine of the liner "Lusitania" off the coast of Ireland.

Possibly the last inspection visit was that by the Swedish Embassy representing the Austro-Hungarian Government in July 1918.

As more suitable accommodation became available attention also turned to keeping the internees in some form of occupation - though many could be found work on the land or in quarries there was a restricted number of guards available to oversee these work gangs - a brush making operation started in mid 1916 which within a few months was employing several humdred men.

Robert Fyson The Douglas Camp Shooting of 1914 Proc IoM Natural History and Antiquarian Society XI #1 2000 pp115/127

B.E. Sargeaunt The Isle of Man & the Great War Douglas: Brown & Sons 1920 - chapter 3 is a semi-official history of the administration of the camps by the then Government Secretary and Treasurer. It concentrates very much on the administration rather than the internees but provides an excellent description of early days at Knockaloe.

Jill Drower Good Clean Fun A Social History of Britain's First Holiday Camp (2nd + considerably extended edition) Scrudge Books Battersea 2018 ISBN 978-0-9927775-1-7 includes three short chapters on its use as an internment camp.

|

|

||

|

|

||

| Any comments, errors or omissions gratefully received The

Editor HTML Transcription © F.Coakley , 2018 |

||