[From How the Manx Fleet helped in the Great War, 1923]

THE way in which the RAMSEY came into the possession of the Isle of Man Steam Packet Company is interesting. She was built for the Lancashire and Yorkshire Railway Company by the Barrow Shipbuilders, and sailed on the Fleetwood and Belfast service under the name of the Duke of Lancaster. She, along with her sister ship, the Duke of York, now the Peel Castle, was purchased by the Turks, and re-boilered, but, owing to the war between Turkey and Greece, she could not be handed over to them.

In 1912 she was bought by the I.O.M. Steam Packet Company, and named the Ramsey.

After completing the 1914 season on the Liverpool and Douglas service, she was taken over by the Government, and fitted out by Cammell Laird and Co. as an Armed Boarding vessel.

Her armament consisted of two twelve pounder guns, placed port and starboard, underneath the Captain’s bridge. Her crew numbered ninety-eight all told.

She sailed for Scapa Flow in November 1914, and on the way North encountered very rough weather, being hove to for a day and a night. When the weather moderated, the first object of interest they sighted was, what appeared to be a British man-of-war, but, when they drew near to her, she turned out to be one of the "Dummy Dreadnoughts", having a large wooden ram, large guns of wood, and an extra funnel made of canvas.

The Ramsey arrived at Scapa Flow, and anchored there, surrounded by ships of all sorts and sizes, including even a representative of the wooden walls of old England in the H.M.S. Imperieuse, which was being used as a supply ship and post office.

After coaling, the Ramsey was ordered to accompany H.M.S. Sapphire and H.M.S. Sapplire on patrol duty. They went out at dusk each day, steaming about two miles apart in line with each other, returning the next day.

The order of procedure on this patrol work has been thus described.

When dusk set in, one of the Marines was sent around the ship to see that all lights were screened. We steamed without navigation lights, and the gun crews were at their guns all the time. The speed of the ship was altered from time to time, from eight to twelve knots per hour, and, if a light were seen, then full speed ahead was made in order to investigate it. Everyone was on the qui vive, even those off watch would be often leaning over the rails, trying to make out in the darkness what a light might mean, friend or foe. When a vessel was sighted, we would steam up abeam of her, keeping about fifty yards off, then flash our searchlight upon her. The voice of our Commander would then be heard, calling through his megaphone, "What ship ? Where are you bound?" If all was found in order, the skipper of the vessel would be told to proceed, we would sheer off, and all would become normal again.

The dangerous work in which the Ramsey was engaged was evident, from the large amount of wreckage frequently seen floating past, showing that some vessel had met with disaster. During the last three months of her patrol work she searched a large number of vessels, and had to put prize crews on some of them in order to take them into port.

The last patrol is described by one of the survivors as follows :—

"The Ramsey left Scapa Flow about 5 p.m. on Saturday, August 7th 1915, for the North Sea. About midnight, a wireless message came through to the Lieutenant-Commander to keep a sharp lookout to the Eastward. All went well until about 5 a.m., Sunday morning, when the smoke of a vessel was seen on the horizon.The Ramsey at once gave chase, and in half-an-hour came up to what, from all outward appearances, seemed to be a large tramp steamer. We blew for her to stop, as we wanted to board her. Both men and ship were well disguised, She stopped, and, when we had got to within a short distance of her, the captain hauled down his flag, which was Russian, and immediately hoisted the German flag. At the same time, the raider opened fire with machine guns, and two 4.6 guns, which were on disappearing mounts, forward and aft. With these, she gave us the benefit of a broadside, sweeping our decks with bullets and shells, killing the Commander, Lieut. Raby, R.N.R., and the officers who were with him on the bridge. At the same time she released a torpedo, which struck the Ramsey aft, just where the crew’s quarters were situated. This was the cause of very many lives being lost, as the majority of the crew were below deck. The Ramsey had no time to reply to the gunfire, as, when the torpedo struck her, the stern was shattered, and she went down in less than four minutes.

In lowering one of the boats it capsized, the occupants being trapped underneath, these included Engineers Pottie and Woods. Some of the crew managed to get on to the bottom of the upturned boat, and, whilst clinging to the keel, were taken off by the Germans, one of them being Assistant Engineer Fanning. Mr. T. Fayle, Chief Engineer was asleep in his room at the time of the attack. This room was situated in the after deck house. The explosion of the torpedo must have carried away the deck abaft this house, for, when Mr. Fayle got to the entrance, he found that part of the deck was missing. He, therefore, jumped into the water. When rescued later by the Germans, he found that his foot had received a severe crush, which naturally crippled his movements.

The survivors, numbering forty-six out of a crew of ninety-eight, were picked up from the water, and from one or two of the Ramsey’s boats that had been lowered. They were taken on board the German ship, which turned out to be the raider Meteor really the Vienna.*

As soon as we were put on board the German ship, the Commander, who, by the way, was wearing an Iron Cross, mustered us on the deck, and then sent us below to get some dry clothes and medical comforts. He afterwards addressed . us, saying that he was sorry to see us in such a plight, and sorry we had lost so many brave men, but that it was the fortune of war. He also said, that as British officers had been so kind to many of their men (Germans), who had, up to that time, come into their hands, it behoved him to do all in his power for us, and anything we wanted in reason we were to ask, and he would grant it. At the same time, he asked if we would like to have a Church service in memory of our lost comrades. We replied that we would gladly accept his offer, He then had the necessary arrangements made on deck, including a lectern, covered with a Union Jack. The German Commander with his officers who were off duty, attended the service.

"We were treated very well indeed, whether it was that the code of honour was higher amongst the original officers of the German Navy than it was toward the end of the war, or whether we had struck an exception, I don’t know, but they certainly were very good to us, and amongst other things gave us plenty of cigars and cigarettes. Extra privileges were also granted to all officers, but they were confined in rooms on deck. Our men were put down one of the ship’s holds, and each one was given a mattress and a blanket. Here we remained until about 3 o’clock in the afternoon. We were then brought up on deck and given an hour’s exercise, after which we were sent below, had tea, and lay down for the night.

"Everything was quiet until about midnight when we heard the ship’s guns firing. We found out later that this was caused by the rounding-up and sinking of a small Norwegian schooner

At the beginning of the War she was interned in a German port, and so became one of the "raiders." She was somewhat similar in build to the Ramsey, but slightly larger and slower bound for England with pit-props, as the crew were afterwards brought on board the Meteor and sent down below with us.

"The hour’s delay caused by the sinking this craft was our salvation, as subsequent history will show, for we were only about an hour’s sail from Zeebrugge, where we would have all been interned, had not British cruisers hove in sight to the great consternation of the Germans. We learned afterwards that our fast cruisers at Harwich received orders at 6 p.m. on Sunday to proceed at full speed after the Meteor and were also informed that the Ramsey had been sunk, and that the Meteor with some of her survivors on board, was making for Zeebrugge.

About midday on the Monday we got orders to go up on deck as quickly as possible. We struggled out of the hold, and learnt from the Germans that British cruisers were in chase, their smoke being just visible on the horizon. The Germans were very much perturbed, not knowing what was going to happen to them, and even decided to abandon their ship.

It afterwards transpired, the Meteor had been warned by a Zep. that was scouting for them, of the pursuit by British cruisers.

When the Germans decided to abandon their ship, there were a lot of Danish fishing luggers about, one of these was commandeered, and into her we were packed, along with their own crew, and the Norwegians, a motley crowd.

In order that the Meteor might not fall into the hands of the British, the Commander with two officers remained on board to place a time fuse bomb in her, after doing which they cleared out and joined us in the lugger.

When the cruisers hove in sight, they were just in time to see the Meteor blow up and sink.

The first cruiser to come on the scene was the H.M.S. Cleopatra. After circling round us several times, one of our officers gave orders to a signalman, who was also one of the survivors of the Ramsey to let them know on the Cleopatra that we were on board. This he did, and the order came back to take charge of the lugger and steer a course that they gave.

"The German Commander, however, would not allow our men to interfere with the navigation of the vessel, pointing out that we were under a neutral flag. We again signalled the Cleopatra telling her what had transpired, and she made off to Commodore Tyrwhitt on the Arethusa, who was cruising round a long way off.

We began to get a little disconsolate, not knowing what was going to happen, and thinking that they had left us to our fate. The German officers in the meantime put their heads together, and had a consultation, the result being, that we were told to go aboard another lugger, which was a Norwegian. By means of a couple of small dinghys they transferred us to the other boat, whilst they made off in the Danish one.

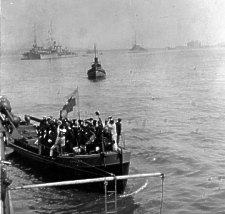

We were on board this Norwegian lugger about half-an-hour, when again one of our cruisers appeared. This time it was the H.M.S Arethusa under Commodore Tyrwhitt, himself. When they found out where we were, they lowered one of their large boats, and sent it off for us. Thus we had the unique experience of sailing under four flags in a very short space of time, being transferred from the German to the Danish, from the Danish to the Norwegian, and then on to the British.

Needless to say we were all overcome with joy when we got on board the Arethusa, knowing that if we happened to meet another raider, we would be able to hit smartly back. We now had something under us very different from the poor old Ramsey with her two small twelve pounders.

Commodore Tyrwhitt mustered us all on the quarter-deck of the Arethusa and spoke to us, wishing us better luck next time. We were then appointed to our respective quarters, and had a good square meal, the first since Sunday evening.

We were landed at Harwich on the Tuesday afternoon, and sent to Shotley barracks, those who were injured being removed to Shotley Hospital.

Unfortunately, about midnight, our dreams were disturbed by an air-raid, and bombs kept dropping extremely near to our quarters. An order was therefore issued that the hospital patients were to be taken to the foreshore out of danger, so, between bombs dropping, and shrapnel falling about from the anti-aircraft guns, we were not certain which was worse, the sinking of H.M.S. Ramsey or the air-raid."

*The Meteor, which sunk the Ramsey, was, prior to the War, named the Vienna, and traded between Leith and Hamburg.

Survivors of the Ramsey arriving at the Arethusa - the name on the bow is 'Eaglet'

(photo courtesy of a relation of one of the officers on board)

|

|

||

|

Any comments, errors or omissions

gratefully received The

Editor |

||