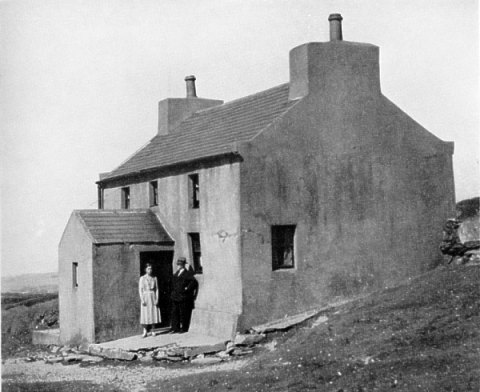

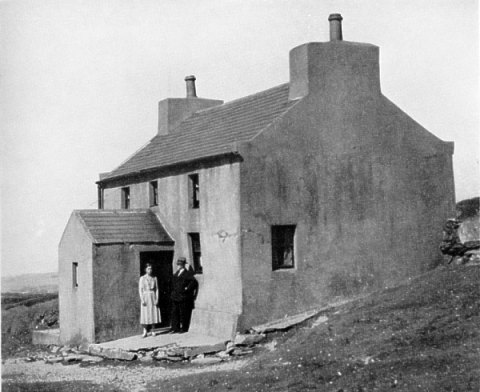

Doarlish Cashen, with Mr. and Voirrey Irving outside their front door

[From The Haunting of Cashen's Gap ,1936]

ON the shoulder of a windswept down, seven hundred and twenty-five feet above sea-level on the west coast of the Isle of Man, stands one of the loneliest farmsteads in Britain-Doarlish Cashen, or Cashen's Gap, as it may be rendered out of the Manx. To reach it you must come right away from the tourist-ridden resorts which provide Lancashire with her summer playground. Man is an isle of contrasts. Out of busy Douglas -a miniature Blackpool-it is but a few minutes' drive into quiet lanes and pretty valleys, where petrol-pumps, advertisements, and road-houses are surprisingly scarce, and even large estates and other signs of wealth and luxury are absent. It is a country of small farms and cottages, resembling Cornwall but less rugged and more varied, or South Wales without industrialism. Outside the tourist resorts a hard and scanty living has to be wrung from a none-too-favourable soil. And in winter the island, though spared severe frosts, is windswept from the north-west to a degree which makes trees rare and restricts vege- tation largely to sheltered spots where, however, semi-tropical plants such as palms manage to flourish. On all sides but the north the island is edged with high cliffs or grassy downs, indented with ravines or glens, down which short streams rush to the sea. These glens are the beauty-spots of Man; and one of the choicest of them, Glen Maye, two miles from the old capital of Man, Peel, is the starting-point for reaching Doarlish Cashen. A few whitewashed cottages and an inn cluster above the waterfall which marks the entrance to the Glen-a rocky chasm choked with a profuse vegetation of ferns, trees, and flowering shrubs which almost shut out the sunlight and hide the path which winds down by the bank of the stream towards the sea-shore. Formerly Glen Maye was haunted by a water-sprite-indeed, the whole romantic neighbourhood is one where superstition dies hard. 'Wise women' (the Manx term for witches) may be all but extinct, but their stock- in-trade-spells and charms, particularly against certain illnesses-still enjoys profitable currency.

At the head of the Glen, beyond the village post office, a stony path parts from the road and winds up among the hills. Soon there are no more trees, and the track is sheltered only by sod hedges; in summer these are clad in a profusion of wild flowers-drifts of harebells ('bluebells') and clusters of scarlet fuchsias-but in winter they are bare and forlorn, accentuating the bleak and monotonous appearance of the landscape. At intervals the track skirts the ruins of cottages and farmsteads, which testify to the depopulation of the district in recent years. Arable farming upon a mere four inches of soil has long been unprofitable here; the land has fallen back to rough grass, and now pastures no more than a few sheep.

Doarlish Cashen, with Mr. and Voirrey Irving outside their front door

At last, after about an hour of scrambling ascent, the path turns a fold in the downs and terminates, rather suddenly, before Doarlish Cashen. The farmstead, perched upon a treeless, shrubless slope, seems utterly isolated from the world. No cart can reach it; no other farm is visible from it; and its nearest neighbour lies a mile away. On the other hand, on a clear day what a natural panorama unfolds before it! Mile upon mile of heathered down falls away to the sea, which is ever changing its colour, its horizon, and the degree of its apparent steepness. To the south, the eye follows a succession of promontories and islands; to the west it catches glimpses, across St. Patrick's Channel, of the shadowy coast of Ireland, the Mountains of Mourne. At midsummer Doarlish Cashen seems to lie out upon the roof of the world, basking in sunshine; but at midwinter it shrinks within itself, shivering under the lash of continual wind and rain.

Approaching the farm, you come upon a house with three outbuildings roofed with corrugated iron, roughly grouped about a grassy 'yard'. This house, which faces west, presents a grey and melancholy appearance, being built of slate slabs joined with concrete and faced with cement. Its concrete foundation is much cracked, and its walls are streaked with crevices caulked with pitch. A small, projecting porch shelters from the gales the front door, which opens towards the south. Immediately upon entering the house the visitor is struck by its sombre interior. Not only are the windows few and small, and mostly not made to open; the whole of the interior is panelled with match-boarding, which has been stained a deep dark brown, almost verging upon black. Beams, ceilings, and walls all of them absorb the light, and impose a mysterious dark- ness upon the rooms. The ceilings too are low, not much above seven feet and six inches in height; while awkward steps and projecting lintels of doors and stairhead make movement indoors slow for the stranger. Entering through the porch, the visitor finds himself facing a short and irregular staircase, carpeted but without rods, leading to the upper floor; to the left of this staircase is a tiny parlour, about eight feet square; to the right extends the principal living-room of the house, about twelve feet by ten in size. At the far, or east, end of this room is a door opening (beneath the stairs) into a narrow pantry kitchen which occupies the back of the house behind the parlour.

The Living-Room at Doarlish Cashen

Both the neat parlour and the larger living-room are more comfortably and tastefully furnished than one might expect to find in such an out-of-the-way place. On the walls hang pictures of a Maori chief with tattooed face, two large water-colours of street scenes in Istambul, and a water-colour of a group of horses and dogs reputed to be by Landseer. The furniture in- cludes a cushioned sofa, five or six chairs, and a table large enough to seat an equivalent number of people. The fire-place with kitchen range occupies the centre of the south wall; in a recess to the right is kept a gramophone, with a few records; and in a corresponding, partly cupboarded recess to the left some books and papers upon a shelf. On a sideboard against the east wall stand one or two pieces of plate, including a christening-cup in Sheffield silver-plate. At night the room is lit with a small paraffin hand-lamp.

Upon mounting the stairs to the upper story you find two rooms; on the right a double-bedded room, plainly furnished with a mahogany chest of drawers and a dressing-table, the floor covered with oilcloth and several Persian rugs; and on the left a second bedroom, smaller by the space occupied by the staircase, which is so boxed off as to leave a boarded recess above it usable as a lumber-shelf. This room holds a single bed and dressing-table, and in one corner an incubator. Both rooms are roofed by the gable of the house, which is held together by cross-beams; walls and ceiling alike are panelled (as on the lower story) with match-boarding.

Such is Doarlish Cashen, a dark, lonely, and rather eerie place, last survivor of a whole group of little farms which once flourished upon the downs above Glen Maye. During the prosperous days of the last century it was the home of a rich Frenchman named Pierre Baume, who was eccentric and miserly, but at his death in 1875 left a considerable sum of money to form an educational trust for the encouragement of music studies in the Isle of Man. Apart from this it has had no remembered history, until in the early days of the Great War it came into the occupation of its present owner, James T. Irving, l and his remarkable family. On the hills around Doarlish Cashen you may any day see a vigorous white- haired man of sixty-three, of medium height, tending the thirty sheep which form the main stock of his farm of forty-five acres. His cheerful, weather-beaten countenance bears the hale look of a man who is out in all weathers, who never suffers a day's illness, who enjoys life and seeks contact with his fellow-creatures. But Irving is no farmer bred to the soil. True, he is of Scottish Border descent; but he himself was born in Lancashire, and followed the profession of commercial traveller. The short, broad fingers of his hands are unstained by heavy manual labour, and suggest rather the nervous energy of the man of thought. Irving is an educated man, pretty well-read, of wide interests and knowledge of the world. He has picked up a smattering of many languages, particularly German, and knows a few words and phrases of Russian, Arabic, and even Hindustani.2 He is a non-smoker and abstemious.

Before the war he represented a Canadian firm of piano manufacturers, from whom he used to receive the then substantial remuneration (including expenses) of six hundred pounds a year. But the war interfered with the Canadian piano trade, and so Irving was forced to seek a livelihood in some other direction. In 1915, during a visit to Peel in the Isle of Man, where lived relations of Mrs. Irving, he came across Doarlish Cashen, then up for sale at the order of Pierre Baume's executors. Irving invested his savings in the purchase of this property, probably paying for the freehold the sum of several hundred pounds. The land was then in fairly good condition, and part of it was leased by the Government for cultivation by a batch of a hundred German prisoners who were interned at Glen Maye. But Irving himself did not at once settle down to a farmer's life. For the first year or two he left matters in charge of his son-who was now grown up-whilst he endeavoured to find new business openings for himself in Liverpool. Only when these failed to materialize did he decide to settle permanently, with Mrs. Irving, at Doarlish Cashen. The farm-house itself required considerable repairing and improving to make it comfortable. Irving spent a good deal of his remaining savings on cementing the walls outside to make them weatherproof, panelling the interior walls with matchboarding to keep away draughts and cold, and adding a porch to protect the front door from gales. One of the interned Germans-a carpenter-helped Irving to under- take this panelling work, and also taught him various additions to his German vocabulary.

Thus by the end of the war Irving was in fairly prosperous circumstances, with his farm well stocked and well tilled, and his son working for him. The Irvings had also a married daughter, Elsie, who has unfortunately been left a widow; she did not accompany her parents to Doarlish Cashen, but continued to live in Liverpool. Then in 1918 a second daughter was born, who received the charming name Voirrey-a Manx form of Mary. Voirrey was many years younger than her brother and sister, and has been brought up to know little of the great world beyond the neighbourhood of Glen Maye.

Gradually the flood of post-war prosperity abated, and the ebb tide of farming set in. Prices of farm produce fell, countrymen migrated increasingly to the towns. Irving ceased to em- ploy outside hired labour, and his acreage under the plough shrank. Then, as time went on, his son became restless. Perhaps he felt that oppor- tunities for a young man to make his way in life were sadly scarce in Glen Maye. However that may be, in 1928 he left Doarlish Cashen, turned his back upon the Isle of Man, and migrated to London, where he found himself suitable manual work, and became self-supporting. To-day his parents hear from him but rarely.

The departure of young Irving made it difficult to farm Doarlish Cashen as before. Now that no labour was to be had, the land must go back to grass, and Irving must carry on with whatever stock he could manage single-handed-or, rather, with the aid of his womenfolk. And so Doarlish Cashen has become what the visitor finds it now -forty-five acres of rough gorse and moss-ridden grass, with nothing but the bare sod hedges to remind one of its former crops. Irving owns, to be exact, some thirty sheep, four or five goats, a dozen geese, and a few chickens and ducks. Yet even stock-rearing in this desolate country is a perpetual struggle against nature. Sheep and lambs stray, or suffer from attacks by great crows; polecats raid the poultry yard; while if chickens are left unattended in the open for more than ten minutes at a time, they are pounced upon by the fierce hawks which everywhere abound. However, in the midst of all these difficulties Irving retains his cheerfulness and sense of humour. He is 'a good mixer', and above all a mighty talker and raconteur. No man was ever less shut up in himself; indeed, he will regale friends and visitors with an almost embarrassing richness of information concerning his own affairs and adventures. As a farmer he is modest, admitting that nowadays he lives chiefly by selling every season some thirty lambs, the wool off the backs of his sheep, together with sundry rabbits, eggs, and poultry. He grows no vegetables, but earns a supply of potatoes by occasionally lending a hand on his nearest neighbour's farm. For nine months out of the twelve his household drinks goats' milk-for the rest, tinned milk. Irving has told us that his total money income for last year amounted to no more than thirty-nine pounds, or fifteen shillings a week- truly a slender figure upon which to maintain a wife and growing daughter.

|

|

|

Mr. J. T. Irving,

|

Mrs.Irving,

|

If you enter the living-room at Doarlish Cashen, it will be long before you can take your gaze off Mrs. Irving, to outward eye the most striking personality in the household. You see a tallish woman of fifty-nine, of dignified bearing, upright and square of carriage, neatly dressed in the style of a former generation. Her grey hair rises primly above her forehead, to frame her most compelling feature-two magnetic eyes that haunt the visitor with their almost uncanny power. Mrs. Irving belongs to a type that you would guess at first glance to be 'psychic'; she herself believes firmly in her own powers of intuition, and has gifts of seeing more than ordinary mortals see with the outward eye. She is a Manxwoman on the side of her mother, who lived in Peel until her recent death at a great age. Mrs. Irving is obviously of wiry constitution and strong physique, for throughout her mother's last illness she made frequent-even daily-visits to Peel on foot to see her. Now, the journey to Peel is eight miles return, and begins and ends with the toilsome path between Glen Maye and Doarlish Cashen. In addition, Mrs. Irving is clearly the mainstay of the Irving domestic establishment.

To her meticulous care and constant work the visitor must attribute the order and cleanliness maintained in the farm-house, the good repair of the clothes and furnishing, and the hospitable entertainment extended to friends. Her voice is musical in tone and commands attention. Like the rest of her family, she is well-spoken and well-informed.

Voirrey Irving

The third member of the Irving household is to be found most days out upon the downs, tramping the hillsides above Glen Maye in solitude, save for her dog. Voirrey is now seventeen, having left school two years or more. Like her parents she is tall and well-built, not holding herself so well as her mother, but promising to look as striking as the latter must have been in her younger days (to judge from her photograph at that time). Voirrey is light in colouring, with a pink-and-white complexion, and fair hair coiled in plaits behind her ears. She carries something of her mother's strange look in her greenish-brown eyes, which, rarely fully open,' seem to observe the world with a penetrating yet half-concealed disdain. This young lady, you would conclude, is old for her years, isolated though those years have been from the ordinary rough and tumble of human experience. She must have passed a curious childhood, without playmates or friends, always in the company of her elderly parents, seeing life from their remote and limited angle. At school she was not ex- ceptionally apt at her lessons, yet she is obviously intelligent and self-possessed. For a young girl she certainly seems undemonstrative, so reserved in fact that you could easily fancy her moody. She is not interested in books, though her father will tell you that she has, or had, a great interest in animals and used eagerly to devour any reading upon that subject that might come into the house. Voirrey's main occupation, in fact, is with the animals of the farm. She is the early riser at Doarlish Cashen, first making her parents their cup of tea, next milking the goats and attending to the poultry, and lastly going her round of the rabbit-snares which Irving has set out overnight in his fields, to see if anything has been caught. There are, of course, household duties to be performed later in the day; but these leave her plenty of time for roaming the hills in search of flowers, bilberries, mushrooms, and so forth.

Voirrey had never, up to the summer of 1935, left the Isle of Man, or indeed visited the northern half of the Isle, beyond Ramsey. Nevertheless, she is rather more sophisticated in her tastes than this fact might lead one to suppose. She is greatly interested, not so much in natural as in mechanical objects, such as motor-cars, aero- planes, and cameras. She knows the names and recognizes the leading points of all the principal makes of automobiles. She pays special attention to the local motor-bus routes and their garage, as well as to the flying services between London and the Isle of Man. She can manipulate a hand-camera with some skill, and seems to enjoy being photographed. There is, indeed, a touch of vanity about her character, natural enough in a young lady who has been brought up as an 'only child' in a very real sense. She wears for visitors a silk or cotton frock, a necklace, and a gold signet ring; she has reached the age of using perfume, but not other cosmetics.

Mona, the sheep dog

There remains a fourth (but dumb) member of the Irving household, Mona, the collie or sheep-dog, a pretty animal with dark brown or black hair, shading off much lighter on the under side of the body. Mona is a charming, friendly creature, only three years old, who does not bark at strangers but plays with them vivaciously upon any excuse. She is not trained to round up sheep in the professional style, but Irving claims for her at least one trick of an unusual kind. Rabbit-catching at Doarlish Cashen has its own peculiar technique, as a later chapter in this narrative will show. Here, however, it suffices to repeat Irving's own account of a method evolved by Voirrey and Mona in collaboration, for catching rabbits without snare or gun. If, in the course of their rambles together (Mona follows Voirrey about everywhere, rather than her father), they come upon a rabbit sitting within view, at a distance of say fifteen or twenty yards, outside the entrance to its burrow, Voirrey will call Mona's attention to the rabbit, whereupon the dog will 'point' her prey, and mesmerize it so that it remains stiff and paralysed, and cannot run away. Thereupon Voirrey, leaving Mona to hold the rabbit's attention, will walk round in a circle, come up quietly behind it, and kill it with a well directed blow upon the head. Irving avers that his daughter has many times performed this feat, which must be of great value in helping to stock the modest larder at Doarlish Cashen.

It may be added that Mona, though she sleeps in the porch of the farm-house at night, with the doors leading to the parlour, living-room, and staircase locked, is of no use as a watchdog-a function which the Irvings prefer to entrust to their geese, who usually sleep in the grassy 'haggart' (yard) outside.

Such then are the inhabitants of Doarlish Cashen, a sufficiently remarkable family, existing under conditions which could hardly be paralleled elsewhere in the British Isles. Their house is remote from the world, on a desolate, windswept down-yet they dress, speak, and behave as though they belonged to ordinary suburbia. Their farm yields little or no produce, yet they appear to fare in decent comfort without, to apply a hackneyed phrase, possessing much 'visible means of subsistence'. Most people would find such a way of living nearly intolerable, but it seems to suit the Irvings, who remain a united, cheerful, and healthy trio of normally intelligent persons. Nevertheless, into their lives has entered a mystery, perhaps one of the most curious and unaccountable mysteries of our times. Their solitary farm has become the scene of what is alleged to be a supernatural visitation-such a visitation as was common enough three hundred years ago, when the reality of witches and their familiars was acknowledged and feared. The haunting of Doarlish Cashen has now continued for over four years, and has been recorded with such detail and circumstance by the Irving family and others that the whole affair lends itself to more thorough examination than is usually possible in such cases. In the following chapters the marvellous story is set forth without embellishment, and analysed in a scientific spirit.

1 He bought it from the executors of Pierre Baume.

2 His former profession used to bring him into contact with many Jews, and he still retains not only a working knowledge of Yiddish, but a curious interest in the race and its ways-exemplified in the Yiddish magical sign which he has painted on one of his fowl-houses.

3 in common with the other members of her family Voirrey has a rather strange dislike of broad sunshine, which seems to hurt her eyes.

|

|

||

| |

||

|

|

||

|

Any comments, errors or omissions gratefully received

The Editor HTML Transcription © F.Coakley , 2010 |

||